COVID-19. The novel coronavirus.

Named for the year it was found, COVID-19 disease and the virus that causes it, SARS-CoV-2, has dominated the headlines to the point that most are overwhelmed with information and the constant need to be vigilant.

We do need to talk about it, to keep it in our attention. So let’s talk coronavirus, but with a twist: What if we remove the ‘novel’? Well, then you have a virus that was first noticed in the 1930s, and began classification as a family not too long after.

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are viruses that belong to the to the order Nidovirales in the subfamily Coronavirinae (family Coronaviridae) and are classified into four genera, Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Gammacoronavirus, and Deltacoronavirus. As easy as A, B, G, D. Wait…

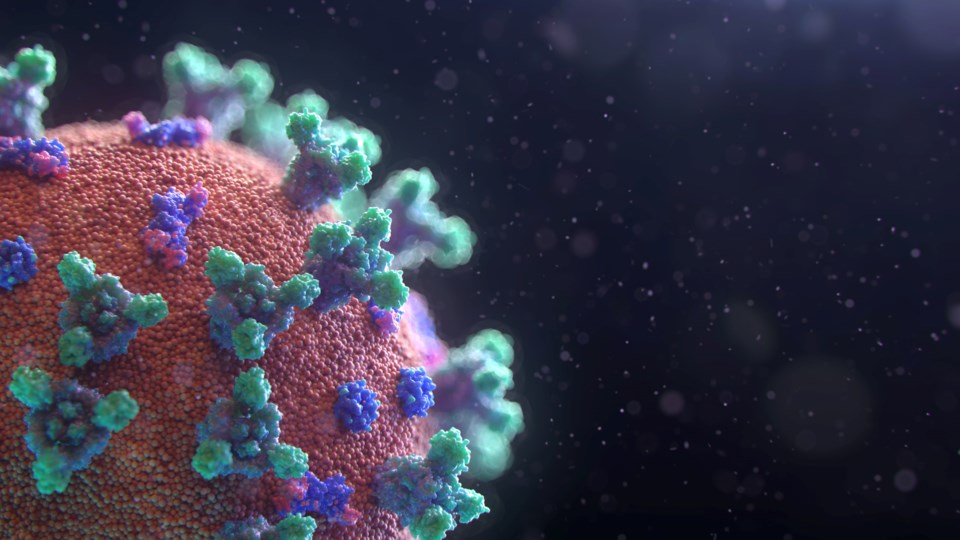

The coronavirus is named for its appearance. ‘Corona’ means crown, a reference to the red spike proteins that protrude from the spherical shape. (As an aside, Red Spike Proteins could be an excellent band name.) It affects mammals and birds, with the alpha and beta coronavirus affecting mammals, and the delta and gamma coronavirus affecting birds.

Though you would think focusing on mammals would narrow the number of coronaviruses to discuss, then you might have to re-evaluate just how many mammals there are. Within the Alpha and Beta coronaviruses there are those that affect dogs and cats (more on that later), but also ferrets, pigs, bats, hedgehogs and beluga whales. Also, humans.

In humans, we have very recent experience with what a coronavirus can do. SARS-CoV-2 has ravaged the world for what feels like an eternity. But perhaps you would be interested to know you have probably already had a coronavirus, or two, or three. There are in fact seven coronaviruses that affect humans.

If you have had a cold or flu, it was likely a rhinovirus. It also could have been influenza, or the adenovirus. However, second most common to the common cold rhinovirus?

Coronavirus. Namely: 229E (alpha coronavirus); NL63 (alpha coronavirus); OC43 (beta coronavirus); HKU1 (beta coronavirus). More than 15 per cent of cases of the common cold are caused by one of these four coronaviruses.

However, the other three coronaviruses should be feared, and respected. You will surely recall SARS-CoV. Un-affectionately known as SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome), this beta coronavirus caused an epidemic and almost eight hundred deaths worldwide in 2003, as well as spawning the SARS-a-palooza concert in Toronto after its erasure in 2014. Because what else do you do to celebrate overcoming a virus then to shove 500,000 people together in a group?

There is also one you may not be aware of, what is truly a case of ‘ignorance is bliss’. MERS-CoV is a beta coronavirus that causes Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Though it does not spread easily from person to person (though the mode of transmission is largely unknown and thought to be respiratory secretions), and it is currently somewhat limited to the Middle East, the virus can begin with fever, shortness of breath, and gastrointestinal issues, and very likely move to serious illness, or death. There are no known cures, and the treatment is based on easing symptoms.

The third, SARS-CoV-2. Un-affectionately known as ‘The ‘Rona’ and other nicknames, you can find up to date information from the Government of Canada.

Of course, there are also many more mammals that we encounter every day. Less often belugas (however, if that is a common occurrence for you, this needs to be an ongoing conversation), and more often our lovable, cuddly pets.

More specifically, dogs and cats. Dr. Courtney Andrews, associate veterinarian at Lockerby Animal Hospital, has had some experience with the alpha and beta coronaviruses that affect our pets – and unfortunately, due to 2020, has had to adapt to quite a few new coronavirus-based aspects of the veterinary clinic.

The Canine Enteric Coronavirus (Enteric meaning of the intestinal system) is a highly contagious intestinal infection seen mostly in puppies. It is spread by oral contact with infected feces (yes, that’s exactly what you think it means) and causes diarrhea. Adult dogs usually just get better on their own, but can be more severe in young puppies. In terms of help, “Treatment is largely supportive,” Andrews said. “Withholding food when symptoms first present and then slowly introducing an easy to digest food. But in severe cases, hospitalization may be required to keep the patient hydrated.”

This virus is not contagious to other species. Neither is the Canine Respiratory Coronavirus. Canine Respiratory Coronavirus is genetically related to the common cold in humans, causes acute respiratory symptoms, and contributes to Canine Infectious Respiratory Disease Complex (CIRDC or ‘kennel cough’). It is spread by respiratory droplets of dogs in close contact.

“Kennel cough symptoms resolve on their own, few patients require cough suppressants, if anything,” Andrews said. “But complications, such as secondary infections or a compromised immune system, can increase severity of symptoms and then require more care.”

For dogs, the coronavirus is sickness, but not death. For cats, it gets a little worse. At first, it is the quite common Feline Enteric Coronavirus, which is once again an issue with breathing or eating poop. Remember, we love animals. The cat could be asymptomatic, or have a mild intestinal infection, but: “Often you just treat it systematically with probiotics or look for other parasites that could be present,” Andrews said. “It is overcome fairly easily with treatment.”

However, if that coronavirus decides to mutate, it becomes something much, much worse. And although quite rare – Andrews has only seen it six times in her entire career – this mutation causes Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP).

“For what’s known as ‘wet’ FIP, fluid accumulates in the chest or abdominal cavity, or both. In ‘dry’ FIP, pyogranulomas form on their organs,” says Andrews. “Normally, within a couple days or at most weeks of developing FIP, it is fatal. There’s not much we can do but try to keep them comfortable. There are promising therapies emerging over the last few years, but larger studies are required before they can be used in general practice.”

So for now, FIP is not a good acronym for a cat.

And really, neither are any of the coronaviruses. Felines, including tigers, are one of the animals that can get SARS-CoV-2 from humans – so are ferrets and hamsters. There is the potential for dogs as well, but no evidence as yet. However it may add a brand new bit of anxiety to your day to know that mink — part of the family Mustelidae, which also includes weasels, otters and, um, ferrets — can not only get COVID-19, but could potentially pass it back to us.

It’s this back and forth, and potential for the virus to mutate that gives even the medical community pause.

“In general viruses don’t pass to different species,” Andrews said. “So if your cat has feline enteric coronavirus, you’re not going to get that virus. Viruses in general tend to be more species-specific. And that’s why we get so nervous when they do mutate and cross species because it’s more unusual for the virus population.”

And while it seems like we have so much information — but also not really enough — for now, keep in good contact with your veterinarian, and if you would like more information, speak to them about the newest medical information regarding the coronavirus and your beloved pet. No matter the species, it is important to keep up to date on the best available information.

If you fear you may have been infected with COVID-19, it is best for you to not only keep away from other humans, but from animals as well. As much as you would want to cuddle with your fur baby when you’re sick, you could make your fur baby sick, too.

And so, now that you’re armed with even more scary facts, it is time to return to quarantine, where you have nothing to do but be anxious. And maybe wait for an album from the Red Spike Proteins.

Jenny Lamothe is a freelance writer and voice actor in Greater Sudbury. Contact her through her website, JennyLamothe.com.