Dr. Theresa Turmel wants her 25 years of research to help those dealing with the grief that comes with the ongoing discoveries of suspected remains of residential school students in Canada.

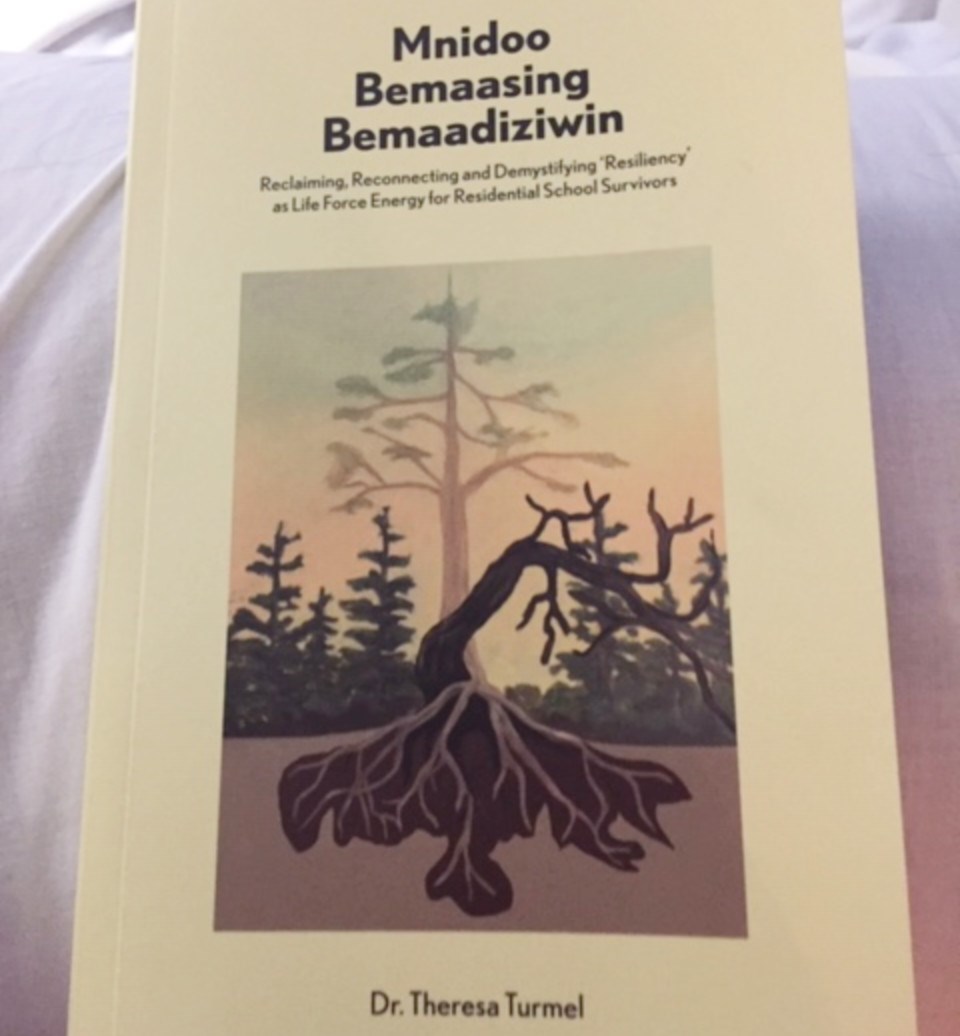

Last year, the Anishinaabe member of Michipicoten First Nation released Mnidoo Bemaasing Bemaadiziwin: Reclaiming, Reconnecting, and Demystifying Resiliency as Life Force Energy for Residential School Survivors, informed by extensive interviews with 13 residential school survivors from Walpole Island First Nation in southwestern Ontario beginning in 2008.

“With what’s going on with the events that have occurred in the last couple of months with the finding of the remains of students, I know that a number of survivors had been triggered. A lot of people don’t like that word, triggered. So I use the word ‘remembering’ - they’re remembering, and after going through so much grief, it’s at the surface,” said Turmel, speaking to SooToday last week from her home in Sturgeon Falls, Ont. “News and stories like this coming out about the graves, it just brings everything back to the surface and survivors are brought back to that, reliving those experiences again. And it’s horrible.”

“I was hoping that my book might be able to help individuals who are going through a really tough time right now.”

Turmel is a former resident of Sault Ste. Marie, having been a student at Algoma University College for three years beginning in 1989 and earning a masters in public administration from Lake Superior State University, all before obtaining a PhD in Indigenous Studies from Trent University in 2013.

She also volunteered and worked for the Children of Shingwauk Alumni Association from 1991 to 2005.

“One of the elders told us that that cemetery was a lot bigger than it was...so we understand that there are graves outside the cemetery, individuals buried outside that cemetery at Algoma University,” Turmel said.

The researcher and author admits that she didn't know anything about the residential school system until she was asked to serve as registrar for the second reunion of Shingwauk Residential School survivors in 1991.

That reunion ended up being somewhat of a turning point in Turmel’s academic and personal life.

“I pretty well became a warrior, an advocate for our people. I debated professors, students alike on the history of what happened to our people,” she said. “It was information that I knew nothing about, that I ended up finding out about - and then that started the whole process of me getting to actually love different people who were survivors of the residential school.”

Her Walpole Island liaison was the late Susie Jones, who was a survivor of Shingwauk Residential School. Jones approached survivors on Turmel’s behalf, after no one responded to an initial call for participants distributed via newsletter in the First Nation.

Turmel says she eventually built up trust with the survivors she interviewed, and they would go on to share their life history and experiences with her - a “special, sacred learning” experience that she holds close to her heart.

Those stories suggest that everything inside the residential school was strictly regimented, and the children were made to speak a language that they had no knowledge of. Their hair cut short, and they were given a uniform. Their old clothes were then burned.

All of it was a precursor to having their Indigenous culture stripped from them.

“They were taken from their homes, some as young as three years old, placed in these schools - and some of them didn’t leave until they were 16. So, they were basically taken from loving homes where they had a traditional way, and we had many ceremonies. When you grow up, there’s many ceremonies that you go through,” said Turmel. “Well, the kids that were taken to the schools, they didn’t have those ceremonies. They didn’t have their culture entrenched in them.”

“They had a totally different lifestyle.”

When asked what she’d like readers to take from her book, Turmel recalled her time as a teaching assistant at Trent University, where she encountered young students who were angry that they didn’t know anything about the residential school system until reaching university.

The students came away with the impression that survivors came out of that system “ruined.”

“They’re not ruined. You can ruin a dress or blouse by spilling stuff on it. Our people aren’t ruined - if anything, yes, they have been harmed, they have been abused. But we’re still here,” said Turmel. “Our life force energy is burning inside each one of us, and when it’s sparked, we’re very strong.”

Mnidoo Bemaasing Bemaadiziwin: Reclaiming, Reconnecting, and Demystifying Resiliency as Life Force Energy for Residential School Survivors is available through the ARP Books website.