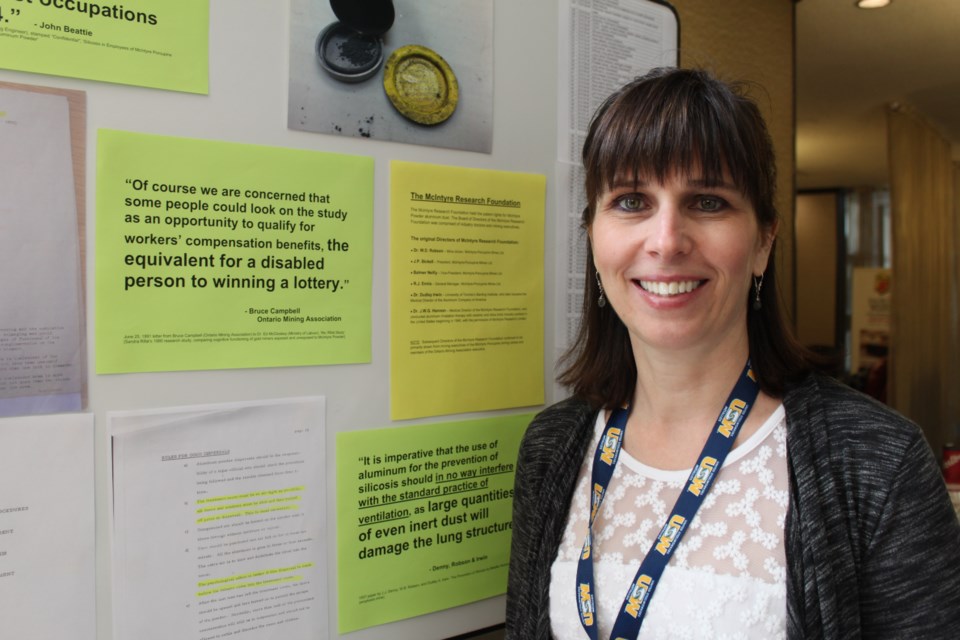

The Day of Mourning will mean something extra this year for Janice Martell, who is the driving force behind the McIntyre Powder Project.

Her research started in 2014, and she went public with her findings in 2015.

“In 2011, I filed a claim for my dad for Parkinson's related to McIntyre powder exposure. He was an underground miner in Sudbury and Elliot Lake, and his exposure to McIntyre powder was in Elliot Lake at Rio Algom Quirke Mine. He was there until the mine closed in 1990, and 10-11 years later, he was diagnosed with Parkinson's in 2001, having started symptoms in 2000. Ten years after that in 2011, is when I found out he had been exposed to McIntyre powder,” said Martell.

McIntyre powder was a finely ground aluminum dust that miners were forced to inhale just before going underground. It started at the McIntyre Mine, and its use spread to other mines in the Timmins area, most of the uranium mines near Elliot Lake, and to other mines worldwide.

Its use officially started in 1943, ended around 1979, after some explosive reporting from CBC's The Fifth Estate and The Toronto Star that September.

“The thought was that if you breathed this deep into your lungs, it would prevent you from getting silicosis,” said Martell.

“My dad hadn't talked about it, so I didn't know he had been exposed.”

Martell's claim with WSIB (Worker's Safety and Insurance Board) was denied, denied again, and then, denied some more.

“I realized that WSIB had this negative entitlement policy that automatically denied any claims for neurological issues related to occupational aluminum exposure. So I realized that we wouldn't be able to win his claim, or even get answers about what the long-term health effects of McIntyre powder were unless we went about it in a different way.”

She dove into research, and spent a few days at the Archives of Ontario in 2014 going through historical documents, including several from an entity called the McIntyre Research Foundation.

She decided to go public the next year.

“We're not going to win this, or get the answers we're seeking by doing individual requests. Because they're all just going to be denied under this negative entitlement policy that the WSIB has.”

In April of 2015, she started a volunteer registry for those who were willing to share their information with her in order to compile a list of how many former miners had health issues, and what those issues were in relation to McIntyre powder exposure.

By her latest count, 545 individuals have been added to the list. Over 50 have identified as having developed Parkinson's Disease.

“Last year, in 2020, the Occupational Cancer Research Centre proved that there is a link to Parkinson's specifically, from the McIntyre powder exposed miners.”

Compensation has begun for those individuals.

“The WSIB has also recognized that it contributed to COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease) as well, so there are many claims that have now been accepted.”

Martell's father passed away in 2017.

“This year's Day of Mourning is huge for me and my family because my dad's name is going on the miner's memorial wall in Elliot Lake, because his death was related to his work.”

It was originally planned for her to be in attendance, but due to COVID-19 related lockdowns, that's not possible this year.

“I was asked to be the keynote speaker, so I wrote a speech, and in anticipation we'd be locked down, I drove up there and recorded it, and will release it on the McIntyre Powder Project Facebook page on Wednesday.”

When asked why it took WSIB until just last year to recognize the McIntyre powder correlation with diseases, Martell was blunt.

“The WSIB has outdated occupational disease policies,” she said.

“They admitted they haven't reviewed occupational disease policies for years, sometimes decades. So they're not following the science. They're not tracking these workers. You're not going to have the science unless you're looking at the workers. Nobody did a study until the OCRC (Occupational Cancer Research Centre) did, and that's because I was finding high rates of Parkinson's as a lay person, just asking the question.”

She said more work needs to be done to identify, compensate, and reduce harm for workers across Canada.

“The bridge to scientific research into occupational disease is mapping and mobilizing. We have to start looking at these workers, and there is a lot more than just these miners. We need a national registry and monitoring system. Nothing is going to change otherwise.”

Andrew Autio is the Local Journalism Initiative reporter for the Daily Press. LJI is a federally-funded program.