Conflict situations involve incredibly complex and entrenched brain activity. But resolving conflict can best be done using simple methods that essentially override intense brain responses.

That was the message Tuesday night of conflict resolver Bill Eddy, president of the High Conflict Institute of San Diego, California. He specializes in family conflict.

Eddy was flown in for this year’s University of Guelph Harshman Lecture, sponsored by the longstanding Harshman Foundation, which supports undergraduate and graduate scholarships in U of G’s college of social and applied human sciences. About 75 people attended the lecture/workshop at Cutten Fields.

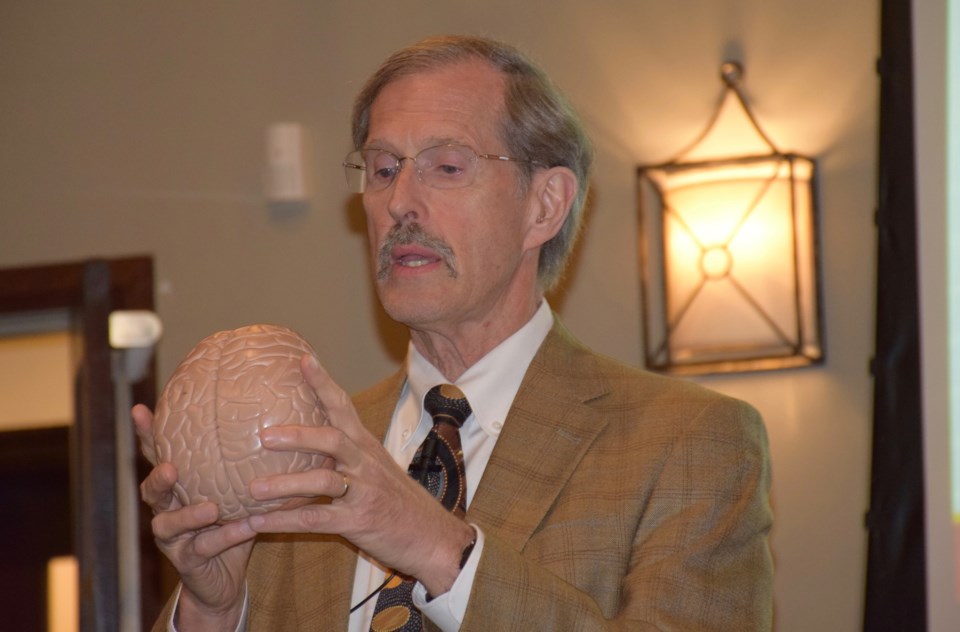

Eddy began his lecture using a plastic model of the human brain to illustrate where conflict resides in our gray matter, and why the emotions that drive it can become so intense and dominant.

On the left hemisphere we have the logical, conscious, reasonable side of brain capacity, where emotions are relatively moderate and positive. This is where we go to think things through and find solutions.

The right hemisphere, Eddy said, while pulling the two halves apart with a simple twist, is our relationship brain – that side that very quickly measures safety and danger, and decides between fight or flight.

Only after the left side decides that things are safe, can we ease up long enough to let listening, thinking and focused attention kick in.

In a crisis – especially in conflict situations like divorce negotiations – the right hemisphere tends to take over, and survival impulses get ramped up. Finding the path to resolution can seem near impossible, unless you say the right things and give the right signals that calm the right brain down and bring the left brain to the show.

The human brain, through a little thing called the amygdala- there’s one on each side of the brain - is intensely sensitive to facial expressions of emotions like fear or anger. Even in infancy a child knows how to read the signs in the face of their parent, and will mimic what they see.

“By knowing this, you can override the amygdala response,” Eddy said, adding that doing so requires a conscious choice and lots of practice. It is thought that adolescence is the time when humans learn these overriding skills, gradually understanding better the difference between a real crisis and imaginary one.

People have social brain matter called mirror neurons that help us imitate others. Through these neurons we influence one another’s moods. We mirror things like empathetic behaviour or angry behaviour. In conflicts, mirroring another’s anger is just asking for heightened conflict.

He advised parents to be very mindful of the fact that children are quick to mirror the behaviour they see, even if it is on television.

Eddy gave attendees at the lecture a few tools that they could use in conflict situations to bring the volume of emotion down and kick-start the reasonable side of the brain.

People, he said, tend to respond very well to simple, suggestive statements in times of high intensity anger. A statement like ‘I know this is important to you,” or ‘I will pay full attention to your concerns,’ can make the difference between making peace proposals or escalating the war.

“It’s takes practice because it might be the very opposite of what you want to do,” Eddy said. “But you have to override the emotion.”

Non-verbal approaches are also highly effective, such as nodding in agreement, leaning in, and showing an interest in the other person.

“Remember, we know that emotions are contagious,” he said. “Negative emotions are contagious, unless you know how to override them.”

Once those negative emotions are overridden, and the rational side of the brain is engaged, conflict mediators can move into analyzing alternatives, giving the combatants choices to help them feel empowered.

In this stage it’s vital to focus not on the upset emotions, nor on the past, but on the future. Making proposals about how to proceed – who does what, when and where – is a positive start to finding a peaceful resolution.