By Warren Schlote

Editor's Note: The following story contains information about sexual abuse that took place in Wiikwemkoong during the mid-to-late 20th century. This information may be disturbing to those who have suffered from sexual abuse. Support is available 24/7 through the First Nations and Inuit Hope for Wellness Help Line at 1-855-242-3310 or the Manitoulin Family Resources crisis line at 1-800-465-6788.

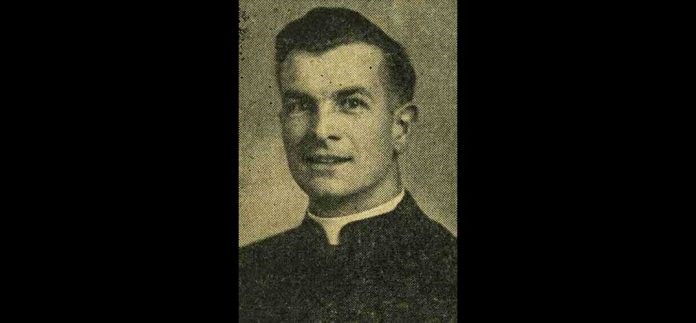

WIIKWEMKOONG – It was on April 23, 1990, according to the Kitchener-Waterloo Record, that the story of the late Father George Epoch began to unravel.

(The crimes of Epoch, who died in 1986, along with Brother O'Meare and Brother Norman Hinton, are now at the centre of a pending class action lawsuit by his accusors in Wiikwemkoong on Manitoulin Island).

The priest at St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in Cape Croker on the Bruce Peninsula reported the allegations he had heard from one of his parishioners about what Father Epoch had done to the complainant.

Two years later, on August 30, 1992, Jesuit Provincial Superior Father Eric Maclean travelled to Cape Croker and offered an apology to the victims of Father Epoch. A further two years later, the Jesuit Fathers of Upper Canada published an institutional apology on Page 27 of The Manitoulin Expositor’s December 7, 1994 edition.

“On behalf of the Jesuit Fathers of Upper Canada, I apologize to the primary victims of the late George Epoch, S.J., for the sexual abuse they suffered,” the notice stated.

The reconciliation agreement between the claimants and defendants mandated the publication of the apology, as well as a personal apology to all validated claimants. The notice stated that the reconciliation agreement also included benefits such as counselling, vocational assistance, written apologies to victims and their families and financial compensation.

“Apologies are at the heart of the reconciliation process,” said Maclean.

“That is why I went to Cape Croker on August 30, 1992. I said there, and now repeat, we are seeking reconciliation because there has been a tragedy in our midst. Though not accepting liability for the aberrant acts of one of our members, the Jesuits express sorrow, regret and humility for the Epoch acts.

“We recognize that healing in sexual abuse cases is of a holistic nature. No one statement by itself is sufficient. An interplay of benefits collectively reaffirming the integrity of the victim is necessary.”

Also in 1994, a number of the Chippewas of Nawash First Nation (Cape Croker) held a five-day-long national healing conference to address Jesuit abuse, according to Toronto Star coverage at the time. The First Nation invited “speakers from across North America” who discussed abuse, deep-seated anger and aggression, substance abuse and cultural oppression.

The 15 victims who had come forward in Cape Croker accepted a compensation package of $25,000 each, as well as a $4,000 fund for improving their education and addressing medical needs, according to a November 5, 1994 story in The Kitchener-Waterloo Record. They also got access to a fund of $500,000 for counselling, eligible over three years, and someone who would chronicle their experiences if they chose to share their stories.

They waived their right to sue the Jesuits and had to undergo a validation process to ensure their claims were valid. At that time, lawyers estimated 40 people were victims of Father Epoch, many more than the 15 who accepted the compensation.

The Jesuits issued a press release at that time which stated “sexual abuse of the young is a terrible thing. But when a priest is the abuser, the loss of faith is magnified. It is hoped that this agreement will advance the process of reconciliation between those who were abused and the Jesuit Order.”

The allegations caused a deep rift in the Cape Croker community, contributing to the fact that only 15 victims signed individual compensation agreements. The rift between victims and the community at large will be explored in further coverage.

On March 27, 1996, the Manitoulin Recorder published a story stating that nearly 10 people had come forward to Meaford lawyer John A. Tamming to share their stories of abuse. On April 20, 1996, Mr. Tamming held a public meeting at the Wiikwemkoong band office and also held private meetings with individuals who did not wish to come forward publicly.

At the time, the lawyer was seeking $500,000 on behalf of a family in Owen Sound but had begun to be contacted by victims in Cape Croker and Wiikwemkoong.

“I know there’s at least three or four people interested in taking legal action in Wikwemikong, and I’ll commence an action on their behalf after I meet with them.

The combined Wikwemikong, Cape Croker and Owen Sound claims will hopefully leverage the Jesuits into settling,” he said in an April 10, 1996 story in the Manitoulin Recorder.

One week later, Chris Polehoykle wrote a story for the Recorder stating that 77 people from Whitefish River, Wiikwemkoong and Kaboni were seeking more than $100 million from four defendants “for mental and physical harm from alleged sexual, physical and mental abuse.” This included 14 primary plaintiffs and 63 secondary plaintiffs, the majority of whom were children, spouses and parents of the primary plaintiffs whose lives would have been impacted by extension.

The lawsuit named Father George Epoch, Brother Norman Hinton, the Canadian Jesuits and the Roman Catholic Episcopal Corporation of the Diocese of Sault Ste. Marie, the diocese which oversees ministering to Kaboni and Wiikwemkoong. They were represented by Ice Lake lawyer Lloyd Greenspoon and this case was unrelated to the similar action by Mr. Tamming.

Seven of the primary plaintiffs sought damages from the estates of both Father Epoch and Brother Hinton. Three sought damages from Father Epoch and four sought damages from Brother Hinton, the latter of whom was said to have died on June 26, 1994 at the age of 84.

That suit sought damages for “emotional and mental abuse; intentional infliction of mental distress occasioned as a result of the sexual, emotional and mental abuse; negligent infliction of mental distress occasioned as a result of the defendants’ failure to exercise their duty of care; negligence as a result of the physical, sexual, emotional and mental abuse; and intimidation,” according to the story in the Recorder.

The editorial in the April 17, 1996 Manitoulin Recorder urged the Roman Catholic Church to allow men to marry and join the priesthood, something it said would encourage more people to join its ranks who would otherwise be hesitant to commit to a celibate life. It also addressed the implication that these policies may suggest women are bad or a temptation.

Soon after the increased legal proceedings and press coverage, more victims and their families began to share their stories in ever-more public forums, including Manitoulin Island’s newspapers.

The Expositor will be following the new developments in this case as more information becomes available as well as sharing stories and past records that bring context to the crimes of Father George Epoch, Brother Norman Hinton and Brother O’Meare from their time in Wiikwemkoong.