When I got the moose harvest tag allocations for 2021, after a major change in the harvest control program, I was driven to write a critical article based on my 27-year career managing moose in northwestern Ontario.

Comments made with regards to that article, the high level of misunderstanding regarding the fundamentals of the selective harvest program and information provided mostly by retired MNRF biologists, prompted two more articles (which you can read here and here).

Those articles raised another concern that I feel needs the attention of the public and Greg Rickford, the minister of Northern Development, Mines, Natural Resources, Forestry and Indigenous Affairs.

That is the conflict between the management of caribou and moose.

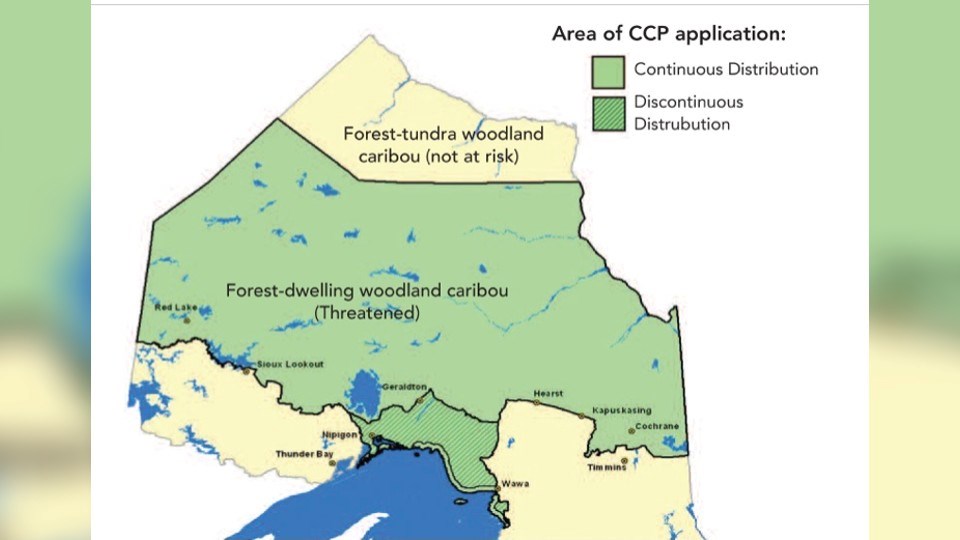

Moose and caribou do not generally live in the same area, mainly due to the impact of wolves on caribou. Where moose occur in densities above 10/100 km2, wolves mainly feed on them, but kill enough caribou to eradicate the population (1). Caribou are a threatened species and there is legislation and policy for preserving and restoring them, but many people believe the policy statements and certain management actions suggest that moose numbers will be reduced in many Wildlife Management Units (WMUs) to achieve this objective.

It may just be a misunderstanding, but the words in these documents do have consequences. The purpose of this article is to attempt to explain the situation as I read them and to show how little regard current MNRF managers, and perhaps politicians, have for their own policies.

Ontario’s resource management is governed by a hierarchy of policy documents from Our Sustainable Future (2) and Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy (3) at the provincial level, to the mid-level Cervid Ecological Framework (4) and Forest Management Guide for Boreal Forest Landscapes (5) to “backgrounders”, strategies, plans, guidelines and policies for individual species (6, 7, 8, 9).

These are only a few of many such documents.

Apparently, the provincial-level documents are out of print and are being rewritten. Of course, all subsequent documents must be rewritten to conform with the new policies. Based on past speed at producing them, that should maintain a significant number of public servants for a decade or so of meaningful employment.

The various levels of policies is how management should be done, starting with general principles (and the “vision”) then working down to the delivery details.

The documents I’ve read are flowing with words like "ecosystems", "biodiversity", "sustainability", "adaptive management" and "social and economic benefits", as well as "transparency" and "inclusion" – of First Nations and the general public. You really can’t argue with them, but then again, because they are rather vague concepts, and written in bureaucratic language, it is difficult to understand exactly what they mean as actions on the ground or how they are to be measured and success determined.

As I see it, they are all statements of vision with no concrete details about how that vision will be fulfilled. Essentially, government staff can sit on their butts doing absolutely nothing and claim to be working diligently to attain these objectives.

As a colleague said to me, “The main problem I see is that the art and science of wildlife management has been lost to some vague biodiversity objectives and sustainability. As long as animals aren't headed to extinction, the top brass are happy. They get a bonus and don't have to work hard or think much. Life is good.“ I’m strongly inclined to agree.

The same words are used in all the documents. More “vision,” but almost nothing tangible regarding “implementation”. Of the ones I’ve read, only the Moose Population Objectives Guidelines (10) appear to have numerical “objectives” and these are justified by the mistaken belief that population "targets” set in 1983 and 2000 were based on “ecological” and “socio-economic“ considerations (10, p 2).

In 1983, they were based on population densities observed in the 1959 and 1969 aerial inventories. I know because I set them in the northwest, and adjusted them upward in the core range in 1992, as many of our populations were headed towards or exceeding the targets.

In 2000, they were essentially reduced to the existing population estimates because failure to control the harvest prevented the population from growing and eventually contributed to further decline. A justification was needed to disguise that mismanagement so new targets based on “ecosystems” and “socio-economic benefits” filled the bill.

There are a number of problems within these management documents.

The first problem relates to public involvement. Although all documents identify transparency (public involvement) as an objective, there appears to have been little meaningful input through advertised open meetings.

They have been posted on the Environmental Bill of Rights website, but how many people actually look there? And besides, the site solicits only comments, not discussion. Further, there is no commitment to act on any comments made. It might be argued that COVID-19 has prevented public meetings, but most of these have been around for a decade or more.

There is a further problem that is specific to moose.

In 2009, moose population objectives (10) were set using landscape level computer simulation. These are being used as real targets, with harvest planning done at the regional level and apparently to the exclusion of district field staff. Even the flow of population and harvest information to districts is stifled (as per personal communications from three former biologists).

So much for transparency and inclusion when it doesn’t even happen within MNRF itself. This is totally inconsistent with the statements that “all Ontarians are encouraged to participate in planning and decision making in moose management and public input will be sought on the specific population objectives.” (10, p. 9) and "to the greatest extent possible, stakeholders and local aboriginal communities should inform the process." (10, p. 7).

That was 12 years ago and I haven’t been invited to participate in one single public meeting.

Interestingly, the 2009 population objectives are considerably below historic estimates when moose were presumably interacting reasonably well within their ecosystems – with wolves and hunting – and when population estimates were unquestionably low. In addition, the objectives appear to be written in stone, with nothing said about adaptive management testing to determine whether they could be higher or provide more social and economic benefit. This should be done through browse surveys (to assess both availability and possible damage to the habitat/ecosystem) and the influence of targetted predator control when MNRF demonstrates the capability to attempt it wisely.

The whole exercise for moose is a plan for mediocrity at best, and certainly not excellence or optimal social or economic benefits. The fundamental principle underlying resource management is that through science and planning, there should be higher populations and more benefits than what raw nature provides. Just look at farming and forestry as successful examples, although game management would not likely be so intensive.

Second, although some of these guidelines have been in place since 2005, there doesn’t appear to have been much in the way of identifiable progress towards achieving the objectives. Certainly First Nations have not been meaningfully involved, but rather, completely shut out of moose management harvest planning. Caribou were just about extirpated from the Lake Superior islands (11) and moose populations continued to decline.

Another criticism is that only in the Black Bear Framework (6) is there mention of fire, a very significant influence on northern ecosystems. Even in that document, nothing is said about how it might be used to sustain the blueberry crops that form a considerable part of bears’ diet (and seasonal revenue to berry-pickers) or to sustain those fire-driven ecosystems themselves.

Forestry can replicate patterns on the landscape, but it cannot replicate processes, especially if planting only conifers and using herbicides to eliminate the early successional trees on which deer, moose and elk depend. Fire is mentioned as a threat to caribou (7).

Equally concerning is the lack of discussion on predators, especially wolves, since bear numbers are currently reduced through hunting. There is “recognition” that wolves are a part of the ecosystem but in the Wolf Strategy (8) emphasis seems to be placed on limiting mortality. There is nothing about using “predator control” to keep wolf numbers in harmonious balance with prey species to enhance the social and economic benefits.

From where I sit, and I'm certainly no expert, wolf control will almost certainly be required if the Lake Superior caribou are to be conserved or restored as is required under the Endangered Species Act.

Apparently it is acceptable, in a “sustainable ecosystem” context, to kill moose and deer, but not to kill wolves to balance the impact of human activity or to protect "threatened species" such as caribou. Scientific management should work to address social concerns, not bow to misinformation and political correctness.

I submit that with moose effectively managed through direct and predictable harvest control and targeted predator management, there will be more moose, more wolves, and more bears than without these actions. This is one of the things adaptive management should be directed to ascertain.

Alaska, probably one of the leaders in big game management, does use predator control (12) and has raised moose densities in several units to more than 100/100 km2 (13). I don’t think I would advocate that as a general strategy, but it should be considered in a number of selected units, if only to assess the impact of such a density on the ecosystem.

Nature is very resilient and I believe will sustain itself unless man makes a concerted effort to destroy it. Ecosystems are large, flexible and although continuously changing, very stable. Only through total neglect and management without assessing the impacts (i.e. “mismanagement”) are ecosystems destroyed.

The point is that you don’t have to work to protect them, but you do have to work not to destroy them.

Moose and caribou will probably always be found in “sustained (but low) numbers”. Perhaps that might meet the sustainability criteria of the documents, but it is not wise management. What is needed is more common sense, more “looking out the window” at what is happening (evidence-based assessment) and more honest public involvement – plus, a lot less policy papers and computer simulations to really manage Ontario’s natural resources for the benefit of its citizens.

There is one real and very “boots on the ground” problem. It applies to all the species covered in these papers, but really comes home with the conflict between moose and caribou management.

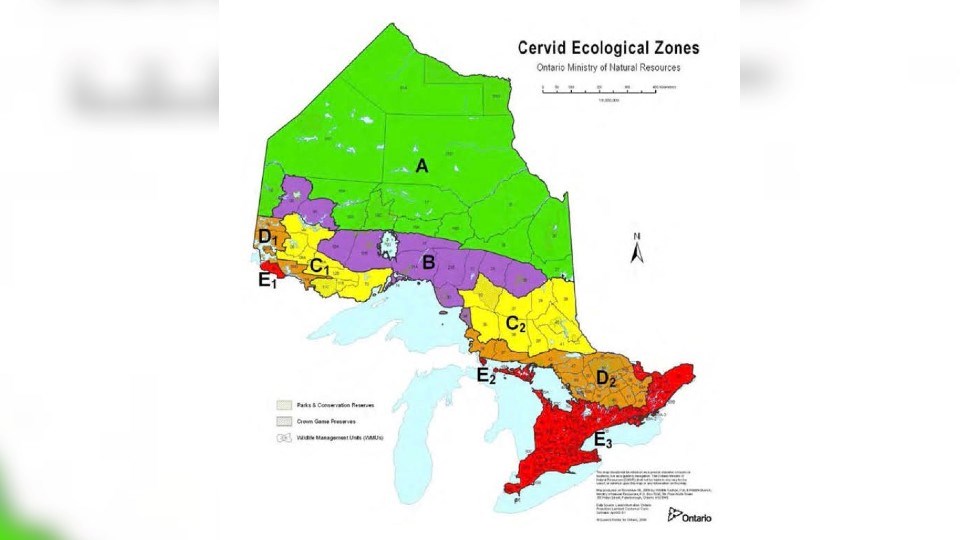

The Cervid Ecological Framework (4) uses Wildlife Management Units (WMUs) as the building blocks for management planning and action. It, somehow in an unexplained manner, created the zones (CEZs) from ecosystem classification documents written by Crins (14), and Crins and others (15). It does not say if real population surveys or distribution information was used in the classification.

I expect it simply included any WMU known to have had any caribou, deer or elk.

The problem is that WMUs were designed exclusively with moose and deer harvest control in mind. They were not intended for caribou, which are prominent in some units and perhaps “occasionally seen”, “transient” or “remnants of former populations" in others. Elk were reintroduced in the 1990s, long after WMUs were developed.

Caribou occur in bands with small numbers in a number of the units where moose are the predominant ungulate. They are not abundant nor uniformly distributed in many of these units.

The policy seems to imply "caribou at all costs" or "caribou without considering the cost".

It just cannot be done within existing WMUs. Either WMUs need to be subdivided to reflect this reality, or there needs to be a (socio-economic based?) reassessment of how many animals it takes for a WMU to be included in caribou range. That, or an alternative way must be found to describe the real locations (range) for management actions to protect them.

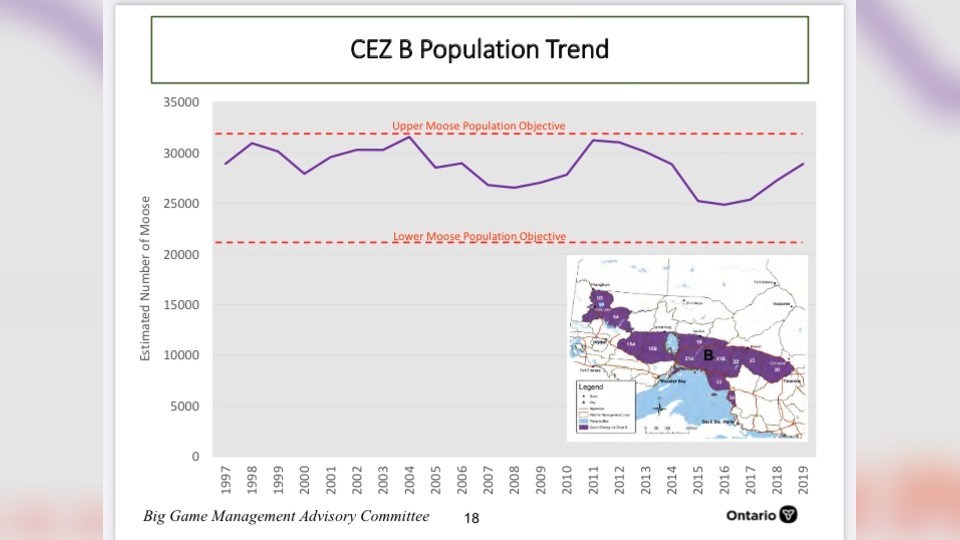

The CEF (3) describes, in general, how different species will be managed within these zones. CEZ B is to be managed for caribou and moose (4, p 8).

Most of it became “continuous caribou range” in the Caribou Conservation Plan (CCP) (7, figure 1).

Moose in CEZ B are to be managed at low to moderate levels (where appropriate…) and caribou are to have impacts minimized and be maintained/restored (where appropriate…). (4, p 8).

“Where appropriate…” may apply to habitat maintenance and creation, but it certainly doesn’t apply to harvest control, which happens within the whole WMU. Even with habitat, you can’t improve it in parts for caribou and ignore the fact moose will still live there but in lower numbers than in good moose habitat. I recently received the results of an aerial survey done in one of the real “caribou units” in CEZ A and more moose were seen than caribou.

Low to moderate moose densities appear to be 15/100 km2 to 30/100 km2 (10, p 9), well above the threshold to maintain caribou. Moose are not being shot to protect caribou, but since moose are already within the planned range (16, p 18), there will be no effort to increase the population. Caribou cannot exist at these densities of moose and if they are to be protected, the moose population will have to be shot down to below 10/100 km2.

Here is the problem that the minister needs to address if the intent of conserving caribou and realizing social and economic benefits from moose are to be realized.

Simply put, the Caribou Conservation Plan and the Moose Population Objectives are in serious conflict in CEZ B. This is especially true regarding the Lake Superior caribou in WMU 21A. That this conflict has been unresolved for more than 12 years illustrates the level of insincerity or incompetence on behalf of MNRF management and possibly the government through inaction by its ministers.

I plan to offer another opinion on the mismanagement and near extinction of the Lake Superior caribou.

It should be noted that caribou have been given a bum rap because of misinformation that has not been corrected, and possibly accepted as fact, by the MNRF.

According to a citizens group (11) advocating on behalf of caribou, "the reality is that all job losses in forestry are from mechanisation and reduced wood supply, caused by overharvesting. In fact, the need for mature conifer forests by caribou benefits the industry. The reality is that no mine or hydro development has ever been prevented because of caribou. The reality is that no moose population has been reduced to reduce predation on caribou – in fact, moose targets and populations are at levels which will not allow caribou to be sustained."

I checked this last point using the moose harvest planning information that I created. I can find no evidence of a planned reduction in moose in the units I looked at. Still, the MNRF plan is to keep moose at low to moderate densities, which in my opinion is well below the potential for this species.

Alan Bisset is a retired regional moose biologist and wildlife inventory program leader with the former Ministry of Natural Resources. He has written and published many papers on moose management, both Internally and in scientific journals. Bisset lives in Strathroy, west of London, Ontario.

References

- 1. Bergerud, A. T., W. J. Dalton, H. Butler, L. Camps, & R. Ferguson. 2007. Woodland caribou persistence and extirpation in relic populations on Lake Superior. Rangifer, Special Issue No. 17.

- 2. Protecting What Sustains Us – Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy. Queen’s Printer of Ontario.OMNR. 2005. 44 p. Online: http://www.mnr.gov.on.ca/MNR_E000066.pdf [link inactive]

- 3. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 2005. Our Sustainable Future. Queen’s Printer of Ontario. 23 p. Online: http://www.mnr.gov.on.ca/MNR_E000002.pdf [link inactive]

- 4. Cervid Ecological Framework. 2009 https://www.ontario.ca/page/cervid-ecological-framework

- 5. Forest Management Guide for Boreal Forest Landscapes. 2014. Queen’s Printer of Ontario. 107 p.

- 6. Framework for Enhanced Black Bear Management in Ontario. 2008. Peterborough, Ontario. 11 p. Online.

- 7. Woodland Caribou Conservation Plan. 2020. https://www.ontario.ca/page/woodland-caribou-conservation-plan

- 8. Strategy for Wolf Conservation in Ontario. 2005. 8 p. Online.

- 9. Moose Management Policy. 2018. https://www.ontario.ca/page/moose-management-policy

- 10. Moose Population Objective Setting Guidelines. 2009. https://www.ontario.ca/page/moose-population-objective-guidelines

- 11. Gord Eason is a retired wildlife biologist from Wawa who has had a long history in caribou management in Ontario. He is my contact with “the Group” which includes a university professor in resource management, biologists and members of the public. They work with the Michipocoten First Nation in the effort to restore the Lake Superior Caribou.

- 12: Intensive Management in Alaska: Alaska’s Predator control program. https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=intensivemanagement.programs

- 13: A Comparison of Moose Management between Alaska and Scandinavia. 2011. S. Brainerd and D. James. Sportsman’s Voice, http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/static/home/library/pdfs/wildlife/research_pdfs/comparison_moose_management_scandinavia_alaska.pdf

- 14. Crins, W. J. 2002. The Ecozones, Ecoregions, and Ecodistricts of Ontario. [map] Prepared for the Ecological Land Classification Working Group. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario.

- 15. Crins, W. J., P. A. Gray, P. W. C. Uhlig, and M. C. Wester. 2009. The Ecosystems of Ontario, Part 1: Ecozones and Ecoregions. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

- 16. Moose Management Review. 2019. https://www.ofah.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/MMR-engagement-presentation-May182019-compressed-002.pdf