This is going to be a short article. I doubt that it will be very sweet to most hunters. If you thought I might be upset by the current practices and history of moose management, this one makes me just plain incensed.

In previous articles, I have focussed on the resident moose hunt. That is because it clearly illustrated mismanagement in the simplest possible way. This one has to do with the allocation of hunting opportunities to the tourism industry.

When I joined the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) in 1976, there was animosity between resident hunters and non-residents. One hunter association in the Northwestern region, where non-residents were most abundant, had bumper stickers printed with “Do a moose a favour. Shoot an American” and “ We miss Americans: by Inches.”

The opportunity to resolve this conflict came with the introduction of Selective Harvest. Because the harvest and tags were limited, it required a decision on how to allocate those opportunities between these sectors.

At the time, the objective of MNR was “to provide social and economic benefits to the people of Ontario.” I expect that objective has been “modernized” with the current bureaucratic lexicon, but I think the principle remains.

As I saw it, economic benefits would come through outfitters and those benefits would be greatest, as far as balance of trade went, when they provided hunting to non-residents. Social benefits were available to everyone through viewing and to resident hunters through relatively low-cost hunting opportunities. With Selective Harvest, all non-residents had to use the services of outfitters who applied and could prove they had provided a moose hunting package in the recent past.

During the 1970s, about seven per cent of all hunters (both resident and non-resident) used the tourist outfitters. Further, about seven per cent of hunters were non-residents who were not restricted to outfitters. On the basis of this information, a committee of regional and provincial biologists (called The Moose Council) recommended that outfitters be allocated seven per cent of the harvest. “Harvest” was chosen over “tags” because moose were the fundamental unit of harvest planning and differences might be expected in hunting success between the groups.

Prior to the implementation of Selective Harvest, a questionnaire was sent to hunters. I don’t know who designed it, but it couldn’t have been the Moose Council. Among the questions asked respondents to answer was this one: “How much of the harvest should be allocated to outfitters?”. It offered four or five choices between 100 per cent and 10 per cent. When the lowest level of this range greatly exceeded the known history, the absolute stupidity of that question needs no further comment.

Thinking it was a fair question, and having no better information on which to base a decision, most respondents chose 10 per cent. I do not know how the many “nothing” write-in answers were handled. Be that as it may, senior staff decided that 10 per cent of the harvest, a 43-per-cent increase over the traditional number, was given to outfitters.

Initially, tags within the tourism industry were allocated through annual meetings where outfitters decided the allocation. Meetings lasted several days and were expensive and time consuming for everyone. They often resulted in disagreements, with some almost coming to blows. There were other problems created by senior staff that led to considerable abuse. The Ontario Moose Allocation Advisory Committee (OMAAC) was established to arbitrate over these disputes. When Bear Management Areas were created, it became OMBAAC.

Originally, OMAAC represented a wide range of interests, including non-hunters and owners of businesses not directly in the moose hunting business. It also included support staff from the Ministry of Tourism and MNR.

As appointments ended, some of these interests were no longer represented. At the time of my retirement, there was only one member, from the OFAH, representing interests other than outfitters. He passed away quite some time ago and I do not know if he was replaced.

My recollection isn’t clear on the order of things, but OMBAAC took on the role of reviewing and approving the entire harvest and tag allocations. To eliminate meetings, and facilitate outfitters leaving or wanting to enter the moose business, the tag allocation became an asset of the company.

Previous tag numbers were used to create “shares”. They were equal to the proportion of the tags each outfitter had previously received in each WMU. Tags were calculated based on those shares.

I considered the allocation between residents and outfitters (corrupt though it was at 10 per cent) to be something of a “sacred trust”. I expected the ministry would treat outfitters the same as residents. When harvest and tags went up or down, then the allocation to both groups would go up or down equally. I contracted for a computer program that did exactly that within the tourism industry allocation.

About that time, an MNR support staff who assisted with the technical aspects of the outfitter allocation left for another job. I assumed some of his responsibilities for several years. The allocation program was a bit awkward to operate because it resulted in partial tags to individual outfitters.

Since partial tags are impossible to use, I had to manipulate the “input allocation” to get the desired output. As I recall, it was always within a tag or two of the original allocation. Nothing to get excited about.

Apparently, one of the outfitters on OMBAAC didn’t like the program that I used, and wrote his own. Apparently, it solved the problem of partial tags. It became the MNR-approved allocation program and he ran it. It also appears to have violated that sacred trust I mentioned earlier.

Tags did not go down for outfitters when they did for residents.

It was at reorganization (1996 I believe) that control of the outfitter tag allocation process appears to have been set adrift from MNR. The chairman was provided funds for an office and secretary in his hometown and probably a salary. My association with them ceased and I have no direct knowledge on how they have functioned since.

I did hear two comments, One, from a Fish and Wildlife clerk, that outfitters seem to get what they wanted. The other, I believe from within the MNR, that they could not verify the outfitter harvest because assessment was handled by OMBAAC. I cannot prove that either is true. Perhaps the allocation of outfitter tags has changed, but the apparent outcome has not.

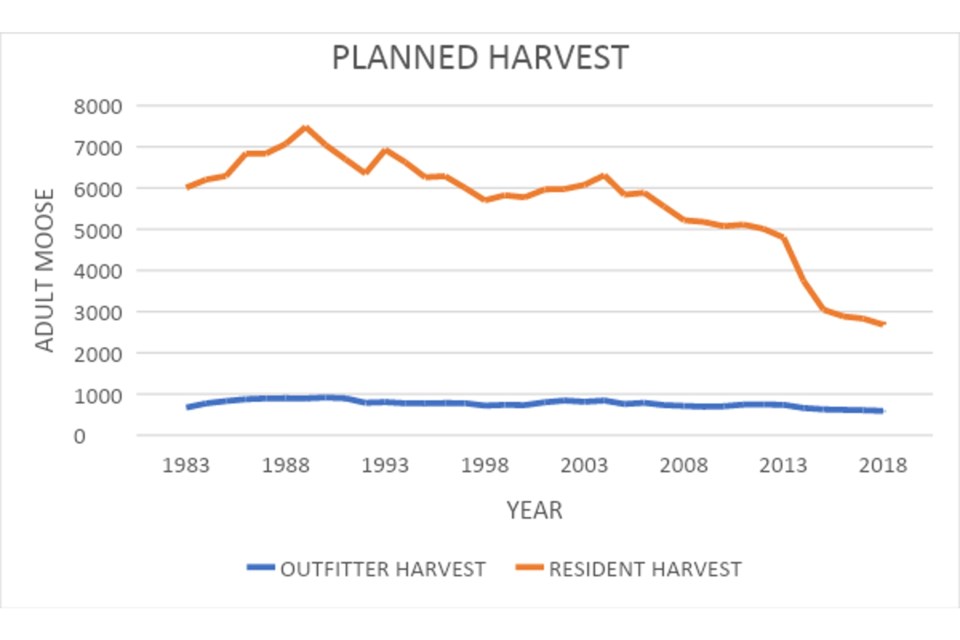

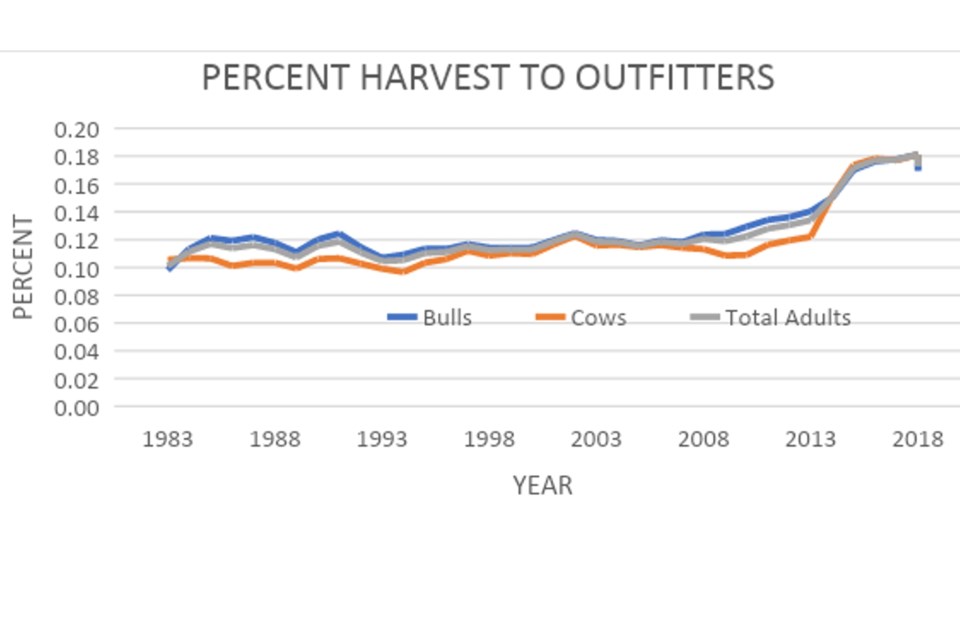

I think that is all I need to say. The graphs tell the story. They were created from the “Harvest Planning” information set I received under the Freedom of Information Act. The history is not of great importance.

The harvest allocation has remained constant for outfitters, while it has declined significantly for residents.

See the graph below.

The allocation to outfitters is now 18 per cent of the hunt. This happened either with the understanding and collaboration of MNRF staff or through their failure to provide adequate oversight of the outfitter allocation process. Neither should be acceptable.

In addition to the specific allocation to outfitters, they are still able to attract resident draw hunters, providing an even greater profit.

In 1999, OMBAAC was replaced with the Big Game Management Advisory Committee (1). It is composed of a broader representation of interests. Of the eight members, three have had careers with MNRF, three with OFAH and two as outfitters (2). It sure looks like an impartial and unbiased body to me. Perhaps that explains why harvests and tag allocations continue above the requirements to rebuild the moose population.

There does not appear to be any representation of First Nations or people who do not hunt. I do not know who is handling the tag allocation within the tourism industry.

Alan Bisset is a retired regional moose biologist and wildlife inventory program leader with the former Ministry of Natural Resources. He has written and published many papers on moose management, both Internally and in scientific journals. Bisset lives in Strathroy, west of London, Ontario. You can find his other submissions by typing “Alan Bisset” into the searchbar at Sudbury.com.

References

- Description of Big Game Management Advisory Committee https://www.pas.gov.on.ca/Home/Agency/569

- Big Game Management Advisory Committee members https://www.pas.gov.on.ca/Home/AgencyBios/569?appointmentId=9195