At the recent successful conference by the Sudbury Arts Council, Rendezvous North, promoting culture and cultural enterprises in the North, I monitored a session on public art.

Before the presenters had their say about how much had been created in the public realm in North Bay and Sudbury, I emphasized two aspects: First, ensure to get the historical information correct — not like Sudbury’s memorial wall that implies Canada participated in the Vietnam War, and; second, aim for a unifying theme to reinforce regional or civic identity.

Since then, I have been to Whitehorse, Yukon, a city from which Sudbury and other places could learn about public art.

A few days of wandering the streets of this small city (population a little more than 25,000) provided a big surprise: the extent and quality of art in the public realm. The 63-metre historic paddle wheeler that is part of the local national historic site sets the scene for more history to come.

The Yukon, which is about the same size as Northeastern Ontario, has five national historic sites with interpretation centres. In contrast, Northeastern Ontario has one at Fort St. Joseph and two at Sault Ste. Marie. I have written in The Toronto Star about this imbalance under the headline “The Hole in Canadian History”, but our local politicians have not yet taken up the cause, something I argued for in this story for Sudbury.com.

The SS Klondike, the centrepiece of the historic site, was one of the numerous steamers that transported supplies on the fast-flowing and ofttimes very rough waters of the Yukon River during and after the main gold rushes. Its interior can be viewed, but one must read accompanying plaques to understand how much wood these steamers consumed: one to two cords per hour.

In this charming small capital city, many street corners are aesthetically decorated with commemorative statues and murals. Since the city is exceptionally clean, with stylishly painted buildings, the whole has an atmosphere of care about public image as well as seeming prosperous. An example of the style of buildings and murals is the Centre de Francophone, which you can see below.

Our first evening, as the early darkness was descending and we returned a great meal in one of the many bistros and restaurants that dot the downtown, we noticed many statues near what we thought were government buildings. As we made our way around the town the next morning, we noticed that in fact the art was widely dispersed, including some murals on private buildings.

As expected, the collection of statues includes significant politicians such as Erik Nielsen and Martha Black.

Martha Black is especially appropriate because she joined the gold rush in 1898, hiking over the Chilkoot Pass. Her interest and research contributions on the region’s fauna led to her becoming a member of the Royal Geographical Society.

In 1935, she became the second woman elected to Canada’s parliament. Erik Nielsen served in parliament as long-time conservative representative from the Yukon.

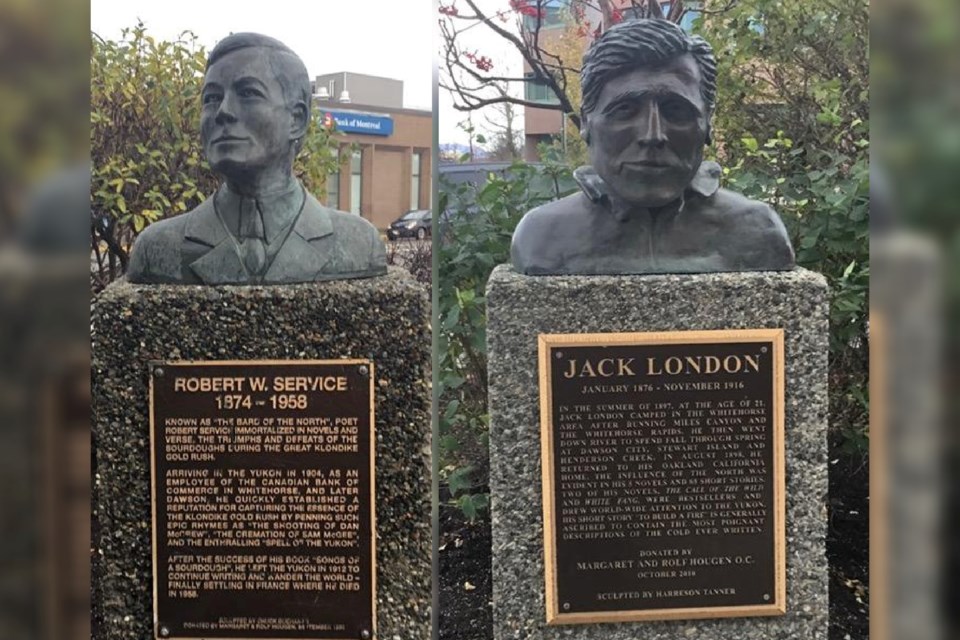

Their small statues are interspersed with ones in similar style of authors such as Jack London and Robert Service. London participated in the gold rush of 1898, lived in and wrote about the North, and was an informed social critic. Service penned the charming poem The Cremation of Sam McGee.

As the locals like to emphasize, McGee was not from Tennessee and not cremated in the Yukon. You can see their busts below.

As usual, the main public art of the 20th Century, the century of war, is a commemorative monument to the deceased soldiers of the region. While not particularly aesthetic, at least it is not historically incorrect like the Sudbury Memorial Park wall, which implies that Canadians fought in the Vietnam War.

One theme we noted, the issue of reconciliation with Indigenous people is directly posed and confronted without overwhelming the viewer. On our first morning, as we started the hike towards Miles Canyon, we immediately encountered a totem pole. It is a healing pole in honour of the difficulties experienced in residential schools. A child is symbolically at its centre. You can it below.

Just past that, we could not help but notice a statue of a woman drumming, symbolically drawing attention to what had long been overlooked. The statue is in honour of missing and murdered indigenous women. Such artwork is not limited to isolated pieces, but part of a concerted effort to raise awareness and foster reconciliation. These pieces are of recent vintage, whereas others reflect earlier attempts to raise historical awareness and pride in the local past. You can see ythe drummer below.

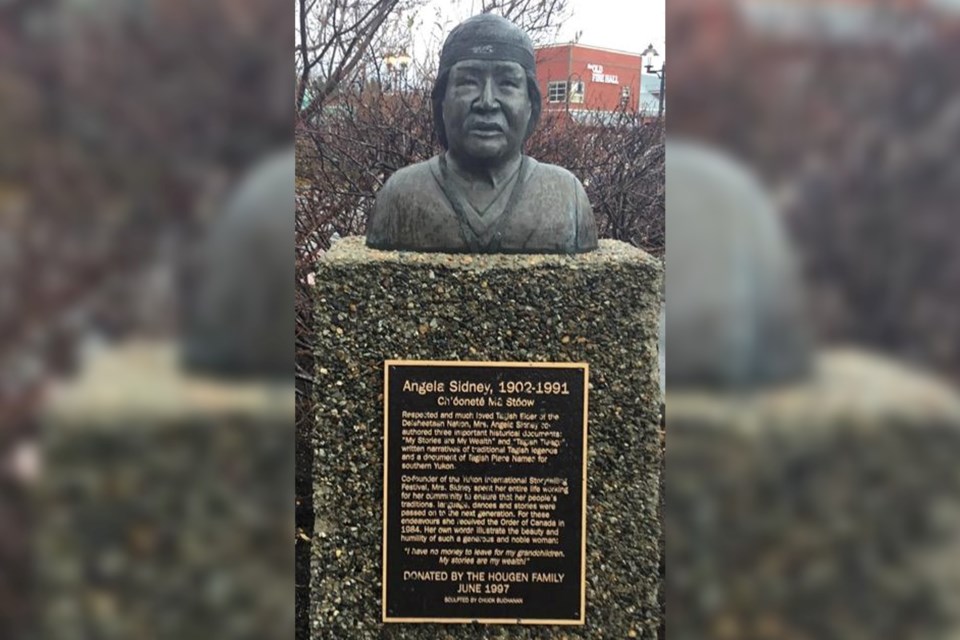

In addition to the heads of political leaders, images of Indigenous people have recently been added in the central area. An example in the same style as the ones of Robert Service and Jack London is one of Angela Sidney. She recovered many Indigenous stories and dedicated her life to reviving local practices and skills. A librarian informed me that her statue had been moved to Main Street recently to underscore the contributions of Indigenous persons to reviving their culture. You can see Sidney’s bust below.

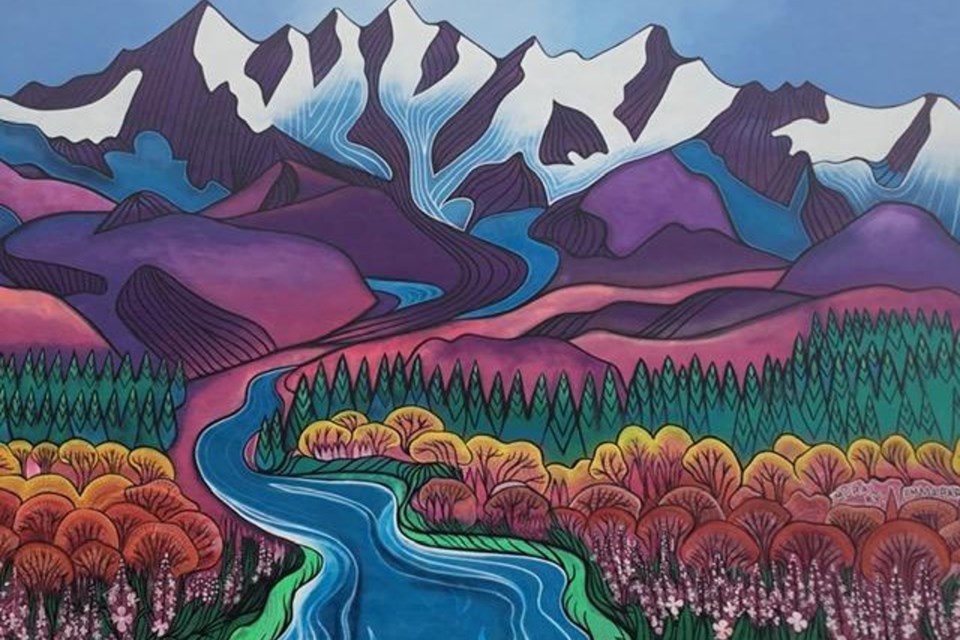

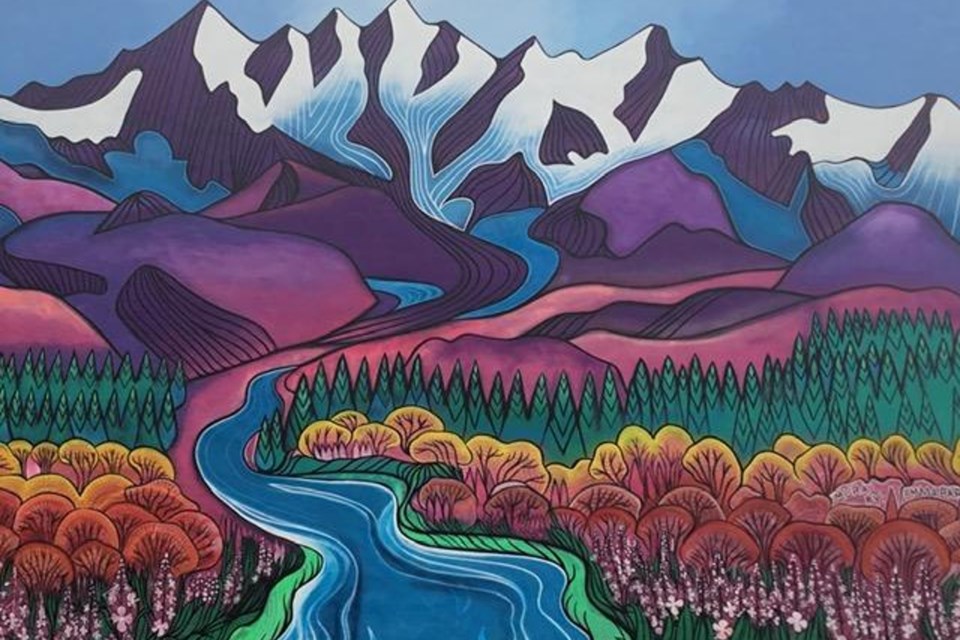

The landscape is big and bold, and it is matched by big and bold murals, such as the one below by artist Emma Barr.

An occasional piece of public art or its placement is very surprising. Part of a totem pole supports the extended roof of what appears to be a private residence. Kaushee’s Place is a women and children’s shelter helping those suffering violence at home, and the totem is reminiscent of a crow with protective wings. You can see the totem below.

Some themes from the past or the present are near buildings to which visitors will undoubtedly go. At the large Yukon tourist office, a mountain goat guards the entrance.

Some of the historical ones are fun, such as of the exaggeratedly tall Mountie (see below), since that group was instrumental in establishing a semblance of law and order during and after the gold rushes. Often forgotten is that the Mounties had the aid of Indigenous guides and deputies.

Last, and perhaps the most important historically, because they changed the social and cultural nature of the region, were the prospectors. They and their successors transformed Indigenous life. Here a symbolic one is appropriately depicted with a dog, their beast of burden, who helped them backtrack if lost, warned of dangers and helped keep them warm.

All the above and more public art is located in an area of five-by-twelve blocks.

What lessons might exist for Sudbury and other centres? Though Sudbury has many murals, thanks mostly to the Up Here festival, and a few notable statues, they are scattered, and few reflect the magnificent landscape around us.

Like the statues by Tyler Fauvelle in Sudbury (the Stompin Tom statue downtown, for instance. You can more of Fauvelle’s work here), many in Whitehorse are poured in bronze, providing permanence.

In Whitehorse, a significant element is the constant use of local historical issues to provide a unifying theme to the displayed art. If identity is to be fostered by public art, here it succeeds by being very present and by unifying rather than fragmenting, even when including negative as well positive aspects of the past. Whitehorse even provides a handy guide to exploring its public art. You can find it here.

Dr. Dieter K. Buse, Professor Emeritus, History, Laurentian University; co-author of "Come on Over: Northeastern Ontario and Untold: Northeastern Ontario’s Military Past" (Sudbury: Latitude 46, 2018/19), which won prize of the Ontario Historical Society for best regional study in last three years.