On 25 December 1918, the Timmins Porcupine Advance ran a story on page 6, entitled “Thirty Died from “Flu” at Burwash Farm”.

As reported in the article: “At the Burwash Industrial Farm near Sudbury (more commonly known as the prison farm), there were thirty deaths from the Spanish [sic: Kansas] Influenza from October 15th to December 5th. A woman who was visiting her husband who was a prisoner at the institution was one of the victims of the disease, while a nurse sent up from Toronto to assist in combatting the epidemic was another.

“The other 28 deaths were among the prisoners. The inquest held into the deaths, as required by the Provincial Act regarding public institutions, showed that at one time there were over 200 cases of the disease at Burwash, the camp doctor, Superintendant Neelands and several guards being among those ill.

“The Government sent a special train to Burwash, carrying three doctors and seven nurses and one of the guards’ dormitories was used as a hospital. All contacting the disease were promptly isolated. The coroner’s inquest decided that every attention and care had been given to the prisoners and effective measures had been taken by the Government to stamp out the epidemic at the Farm.”

What the article did not specify is who the prisoners were. It also did not say why a Timmins newspaper reported on Sudbury events.

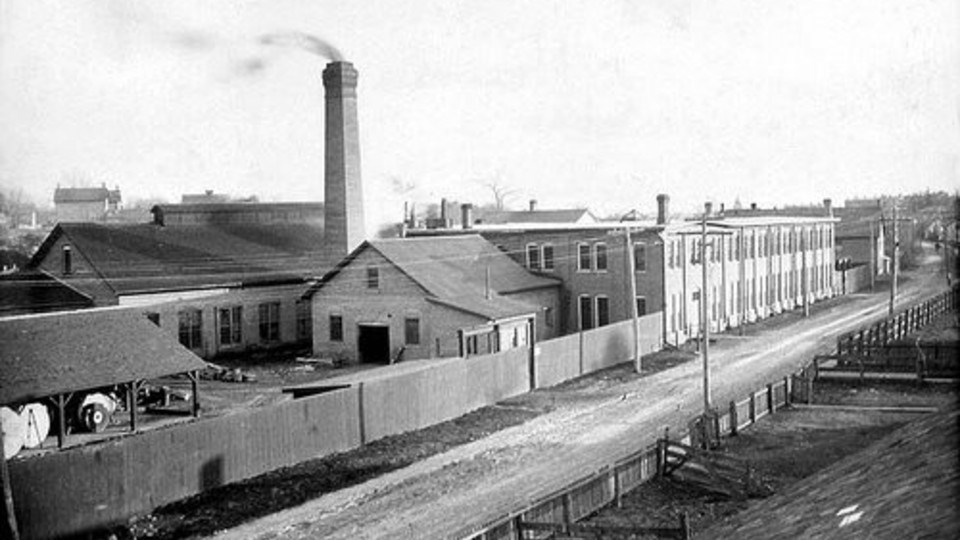

The Burwash prison, established as part of the Ontario prison reforms of 1909, underwent notable changes due to wartime: In 1916, the number of inmates had doubled because 200 prisoners from Guelph were transferred when the Guelph penitentiary was turned into a hospital for war veterans. By November 1917, Burwash comprised five camps. It had 355 men in custody with 143 at Camp 1, 150 at Camp 2, and 62 at its timber cutting and road building outposts at Camps 3, 4 and 5. The farming operations, working out of Camps 1 and 2, had horses, beef cattle and crops. (A short history can be found at https://burwashindustrialfarm.weebly.com/history.html)

In 1918, additional prisoners may have increased the number of inmates because so-called enemy aliens, or persons whose background included the countries with which Canada was at war, were forced to work in industry in return for being released from the Kapuskasing internment camp.

Mostly Ukrainian and German, they had been arrested and incarcerated in 1914, but in 1916 due to wartime labour shortages, were released into the custody of industrial firms. Those who refused to work or objected to the work conditions, were jailed. At least 39 of those who refused industrial work were sent to do hard labour at the Burwash farm. (For comparative information see Bohdan Kordan, “No Free Man: Canada, the Great War and the Enemy Alien Experience”).

These men had been taken from their families, imprisoned under harsh conditions at Kapuskasing (building their own huts, clearing fields, building roads) and forced to work in the bush. Some despaired and committed suicide or went insane, some died of accidents felling trees and some returned to their previous homelands later.

In Canada during World War I, nearly 10,000 people were imprisoned and another 80,000 had to report each month to police. It remains a dark spot in Canadian history, because these people were arrested or identified for who they were, not for what they did.

The issue is what happened to them at Burwash? Were they more susceptible to disease because they were already weak and undernourished? The inquest, as expected, stated that the government had done all that was possible for the inmates. Yet, given the increase in numbers during 1916 and 1917, the dormitories must have become crowded.

If the inquest report provided names perhaps one could find out if deaths were higher among the so-called enemy aliens than the minor criminals being ‘reformed’ at the farm. The Timmins paper was probably interested because the sheriff there was proud to be rounding up aliens who had not registered and hence he may have been responsible for seeing that those released from the Kapuskasing internment camp who had refused to work were sent to do hard labour at Burwash.

So many questions, so difficult to find precise answers. But chances are high that many of those who succumbed to the 1918 flu epidemic were victims of one of the blights in Canada’s history, just as at present many of those who succumbed to the corona virus are victims of long-term care blight.

For more on Kapuskasing during World War I see Dieter K. Buse and Graeme S. Mount, Untold: Northeastern Ontario’s Military Past (Sudbury: Latitude 46, 2018), Vol 1.

Dr. Dieter K. Buse is Professor Emeritus, History, Laurentian University. He has published many studies on modern European history and more recently on our region, including Come on Over: Northeastern Ontario (co-authored with Graeme S. Mount) and the two volume work, Untold: Northeastern Ontario’s Military Past vol. 1: 1662-World War I and vol. 2: World War II-Peacekeeping (available from Latitude 46, Sudbury). Buse, as an educator, researches and writes as his social contribution to better understand the present in historical context.