Behind each golden pint, each bittersweet sip, each bubble of carbonation, is a microscope assembly line of organisms and a brewer who knows a thing or two about science.

People have been brewing beer since 4,000 BCE, long before anyone understood the science behind why the ingredients resulted in an alcoholic, bubbly brew. In 16th century Europe, beer was considered a staple in every household's diet, providing an essential source of calories and nutrition.

While it's maybe not a necessary component of our diets now, beer remains a significant part of our culture and social experiences. Other than for its intoxicating and crisp effervescence, beer has most likely stuck with humans throughout a changing world due to its simple ingredients.

Beer consists of four main ingredients: malted barley, water, hops and yeast. However, it's only in the last 100-120 years that we have figured out how and when all these ingredients are interacting to produce beer.

Microbes, molecules, and malt

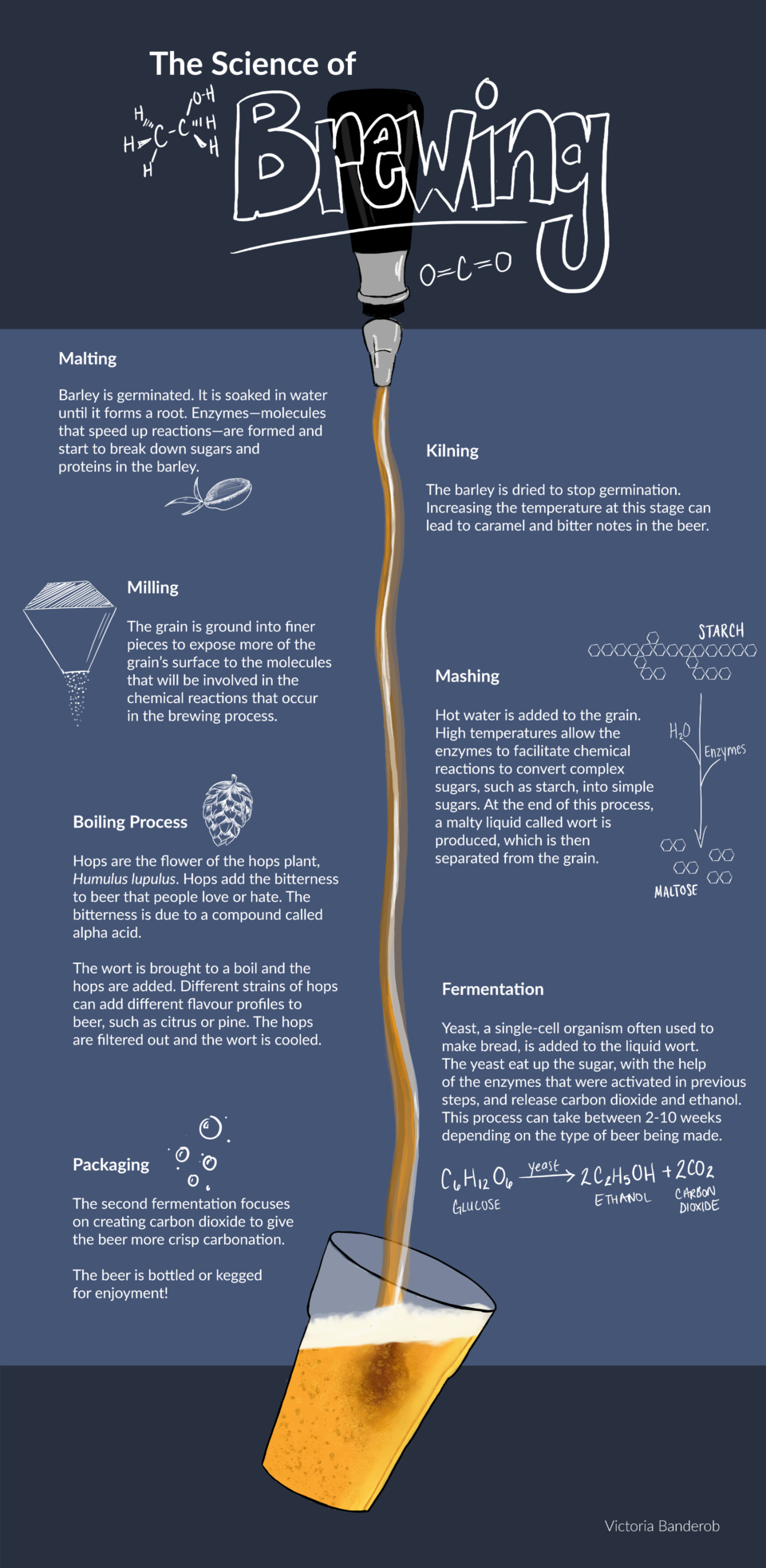

Barley is a grain that provides sugars that will be converted later on in the process to alcohol and carbon dioxide bubbles. In the malting stage, barley is soaked in water until it sprouts. The barley releases enzymes that start to break down sugars and proteins. Germination is halted by warming up the barley in a kiln to dry it (a process that can accentuate caramel and bitter notes in the final product).

Next, in the milling stage, the brewer mills the barley to grind it into finer pieces. By grinding into smaller pieces, more of the surface of the grain is exposed to participate in the chemical reactions. Next, in the mashing stage, the brewer adds hot water to the grain to activate the enzymes that convert complex sugars into simple sugars. The simple sugars are important for the yeast in the fermentation stage. The liquid at the end of this stage is called wort — a malty liquid without the booze or the bubbles.

Sweet on the eyes, bitter on the tongue, hops are flowers from the Humulus lupulus plant. The brewer adds hops during the boiling process to imbue the wort with a sultry bitterness that derives from alpha acids in the hops. Brewers will use different varieties of hops grown throughout the world to add certain desired flavours and bitterness to their beer. This bitterness balances out the sugar from the barley. The oils in hops play a second role in extending the shelf-life of the beer.

Finally, the climax of the brewing process takes place. The brewer adds yeast, a single-celled organism, to the wort to start the fermentation process. Yeast is also known for its leading role in making bread. With the help of the enzymes that were activated in the previous steps, yeast eat the simple sugars from the barley. The byproduct of the consumption of sugars by yeast is ethanol (the alcohol) and carbon dioxide (the bubbles).

Lastly, more carbon dioxide is added to the beer, either by pumping it directly into the beer or by adding more sugar before bottling the beer, so once the bottle is sealed, the remaining yeast converts it into even more bubbles.

In the 1700s and 1800s, as more sophisticated microscopes became available, scientists started recognizing the role of yeast in the fermentation process. After astute experimentation, Louis Pasteur (from whom we get the word ‘pasteurization’) published a paper in 1860 that shed light on the chemical reactions and environmental conditions underlying fermentation. So, while humans have been brewing beer for thousands of years, discovering the science behind the process has given brewers the ability to more precisely control the fermentation process, experiment, create new flavours, and reproduce beer consistently on a large scale.

Brewing infographic. (Created by Victoria Banderob)

Brewing infographic. (Created by Victoria Banderob)

A brewer's lab

Every science you can think of has a share in brewing, from chemistry and biology, to the less obvious physics, engineering, and anthropology. Despite the long history humans have with brewing, researchers continue to explore the behaviour of the microorganisms, the chemical compounds in hops, and the new technology and machinery to make brewing more efficient.

"There is so much science that goes on … and that really is what makes the difference, in my opinion, of a good beer versus a bad beer," says Sudbury's 46 North Brewing co-owner and brew master, Graham Orser.

Orser started off as a hobbyist brewer, making less-than-great beer with friends as an excuse to hang out on the weekends. But over time, with more practice, his beer got better and his passion for the process grew.

The brewery is Graham's lab, where he counts yeast under a microscope and ensures unwanted bacteria aren't growing.

"Keeping those yeast alive is a really big part of our job."

Like humans, yeast need to be fed for them to survive and propagate to the numbers needed to ferment a batch of beer. Yeast reproduce very quickly so brewers can continue to use propagated yeast to ferment many batches of beer.

Graham works with six different strains of yeast and two strains of bacteria. Beer takes on different flavour profiles depending on the yeast that is used, and certain bacteria help produce different types of beer, like sour beers.

Sour beers are particularly tart and tangy, and the type of sourness depends on the bacteria used. Lactobacillus creates a sourness akin to a lemon while Brettanomyces creates what Orser calls a funk, not unlike a barnyard funk. One way to sour a beer is to add bacteria to the wort before adding hops and yeast. The bacteria eat some sugar and the resulting compounds provide the sour flavour.

Consumers continue to find new and interesting beer, like sour beers, on the shelves of the LCBO and bottle shops. It has also become extremely easy for home brewers and craft brewers alike to get their hands-on ingredients from all over the world.

With so many varieties of yeast, bacteria, and hops available, experimentation is an exciting part of the job. Brewers are faced with the challenge of keeping up with consumers' changing palates, even from season to season, while also trying to push boundaries with unique combinations of ingredients and brewing conditions.

"At least every week I try a new batch of beer that I've never made before … if I'm not brewing something new every week, I'm always thinking about something," Orser said.

However, experimentation for brewers is not only about innovating and pushing boundaries. It's also about perfecting the beer you do make.

Angus Hilts, a microbiology student and homebrewer, said style is also important.

"The real art of brewing, in my opinion, is not making good beer, which isn't too hard with some basic knowledge, it's making beer to style."

Hilts spends a lot of time perfecting some classic styles, like British bitters and German lagers.

Research and experimentation are key parts to brewing and perfecting a new beer, from researching the recipe, to figuring out the mineral content and temperature of the water being used in the brewing process. Throughout the experimentation process, a brewer will have to tweak things like temperature and acidity to have a successful brew. And sometimes the tweaking is just to make the beer more to the brewer's liking.

Sophisticated technology has helped brewers achieve consistent batches of beer. With the low-cost of computers, even small breweries like 46 North Brewing can have an automated system that guarantees precision. Temperature, for example, needs to be kept precise as it dictates how the enzymes, yeast, and bacteria function.

While technology has helped make the process more efficient, brewing is still an art that requires the brewer's touch. Orser said your basic senses, like touch, feel and smell and sound, are still critical tools in the process.

"You can just hear when things are running and then when things change, they have a different sound and it's like that's your indication that either something's gone wrong or there's been a change process.

"We're still just adding water to barley and mixing it up."

Bringing the brewery to your home

The wonderful thing, Hilts said, is brewing can be incredibly simple or amazingly complex.

"Home brewing is as hard as you want it to be,” he said. "In general, all you need is a pot and a bucket to get started and that could get you some pretty decent beer. On the other end, you can get into big electric systems with temperature controllers and conical fermenters."

Orser started small, too.

"I would say always just keep it simple … start off with what I would call like a SMASH beer, which is a Single Malt And Single Hop — simple beer."

Both Hilts and Orser have the same piece of advice — control your variables, changing only one thing at a time. If you change many things at once during each stage of the brewing process, you won't know what change caused the effect you're seeing in your beer.

"It's kind of like cooking," Orser said. "You generally can brew a batch and not stray too far from what I consider your kind of golden ratios and still make a good beer at the end of the day."

"Your first batch of beer is not going to be great. My first batch was horrible … still drank it!"

Enjoying a beer is more than just enjoying the taste. For some, it's about the process of making it, and for others, it's about who you're drinking with and what you're drinking to. Whatever the occasion, clink to the brewers — the artists and the scientists — who conducted a symphony of microbes and molecules to get that amber nectar into your glass.

Victoria Banderob is a science communication student at Laurentian University.