How, if we live in a just society, can a parent be expected to give up custody of a child in order for that child to receive medical care?

Three years ago, Sudbury.com introduced you to Dr. Nicole Desmarais. Faced with little choice, the Sudbury mother was forced to make her adopted son a Crown ward in order for the boy to receive the intensive therapy he required to overcome severe mental health challenges.

Desmarais adopted the boy eight years ago from a Serbian orphanage, a place that, based on her description, sounds like something out of the Dark Ages. She described how the child was kept tied to a mattress in a locked room from infancy to age four.

The result of this physical and psychological torture — what else could it be called — is a child for whom the world is a cold, dangerous, scary place.

Those are formative years for the human brain. The result: the child can’t form normal emotional bonds like the rest of us. He can’t process his feelings in a healthy way. He sees the world in terms of potential threats — not as a warm place, but as a place that can, and will, hurt him, unless he strikes first.

This trauma manifests in attacks on other children, the killing of a pet, the attempted strangulation of a toddler, stealing, weapons, molestation. One doctor described the boy as a "wildcat."

Intensive residential treatment is available and is the boy’s best chance to live a normal, fulfilling life. At $1,000 a day, it’s expensive. But likely not more expensive than the millions of dollars the child could cost the system in pain, suffering, police work and prison time if he doesn’t get the help he needs and carries his mental health issues into adulthood.

This worst case scenario is not guaranteed, of course. But the likelihood does become greater without medical intervention. It's also likely the least desirable outcome, for the boy and for society, becomes even greater if the child loses his family.

So, Desmarais gave him up, but she didn’t give up on him. She continues to fight for him to this day, launching an ultimately unsuccessful lawsuit against the government and getting some support from the NDP, who raised the issue at Queen’s Park.

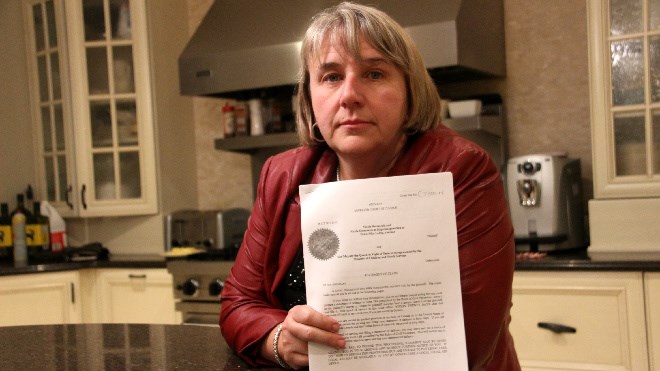

Last week, we caught up with Desmarais. In what might be a last ditch attempt to restore her parental rights, she took her case to the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, hoping against hope to get her son back.

In the appeal, Desmarais argued that had her son been born in Canada, he would have received the care he needed. Her appeal was denied.

The court acknowledged the family’s difficult circumstances, but said the tribunal doesn’t have the power to impose a higher level of care. But it also said Desmarais would have to have shown her son didn’t receive the same standard of care as other children in similar circumstances.

And it’s that last statement that should stick in your craw. Because the court is exactly right. Unfortunately. Sadly, Desmarais’ experience isn’t unusual. It’s not an isolated case.

Ontario treats other families in similarly terrible circumstances just as poorly.

Back in 2000, Judy Finlay, Ontario Child Advocate from 1991 to 2007, addressed the issue and called for changes. When he was Ontario’s ombudsman, Clare Lewis issued a report in 2001 on families being forced to make children Crown wards to get necessary treatment.

Back in 2005 when he was the newly minted ombudsman, André Marin used his first yearly report to address the issue. He said the ombudsman’s office had received dozens and dozens of reports of Ontario families being split up so a child could receive care.

This should not be happening in a country that prides itself on universal health care. We cannot be so smug as to pat ourselves on the back while families are being broken up so a child can receive treatment. It’s unconscionable.

Making matters worse is that, at least according to Marin’s report, it wouldn’t take much to fix the problem. As he pointed out 12 years ago, the province is willing to pay for the treatment. The rub is, the government will only pay if the child is a ward of the state.

As Marin said, all the province needs to do is to start covering residential treatment for children like Desmarais’ son.

And like we asked three years ago, in a country where access to health care is considered a human right, is this the kind of impossible choice we want our friends, neighbours and family members to face? To give up a child to get care?

The answer seems simple to us.