During the pandemic online shopping has multiplied. The approach has become common thanks to improved technology in phones, computers and transport organization. Only recently has ordering foodstuffs gone online and appears to be on the increase. Yet, it is, like working from home, not new. (You can check out Buse’s column on the history of working from home here.)

At present, as an example, the Real Canadian Superstore on Lasalle Boulevard lets you order groceries by phone or internet. The retailer’s ad explains clearly how to select items, and the costs, including extra charges for time of delivery as well as delivery itself.

Other online retailers offer assurances that you will receive the grocery choices you want and that they will be in good condition. Even before the pandemic, in 2018, about 1.5 per cent of groceries were ordered online and the trend was increasing. Now, an estimate puts it at more than five per cent.

During the pandemic, services for vulnerable persons have included buying and delivering groceries for neighbours (which I have done) and having volunteers get groceries and deliver. That social service has existed for a while, but the commercial variety is the supposed novelty.

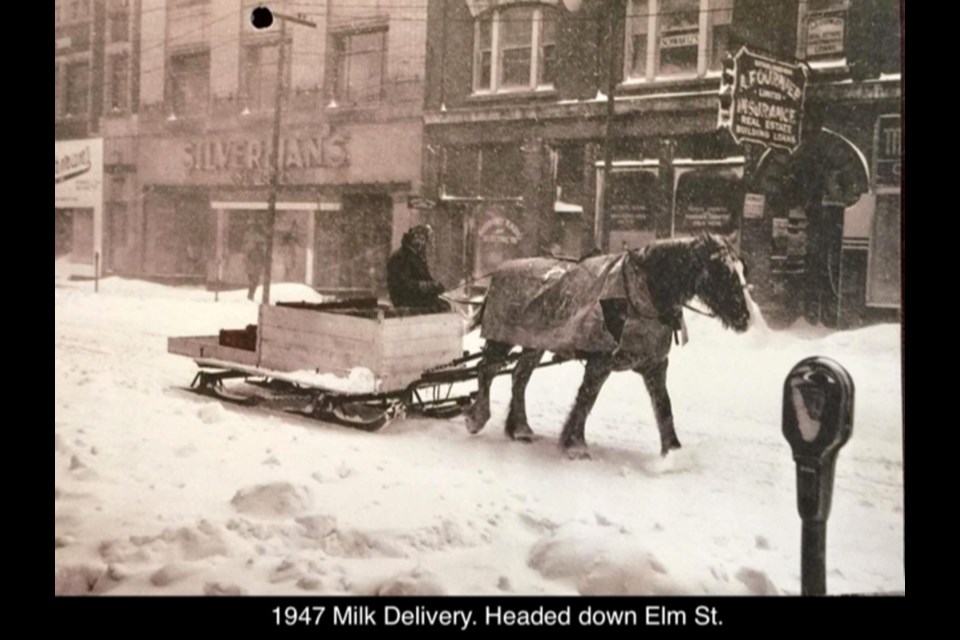

This is not as new as many think. Older people remember milk in glass bottles delivered directly to one’s house by horse and wagon. Some houses still have little boxes near their entry with doors on both sides, so the milkman could pick up empties with payment for the full replacements.

In Sudbury, for example, the practice was going out of style in the 1950s, with one local dairy posting the following ad in 1955: “Palm Dairy milk delivery. The very last day of delivery by horse-drawn milk wagon in 1955.” The accompanying picture shows a Palm Dairy horse, wagon and uniformed milkman with his metal milk jug carrier on Drinkwater Street. Some claim Standard Milk continued deliveries beyond that date.

Let us time travel to Barrhead, a small town in northwestern Alberta during the 1950s. At least three grocery store clerks, always females, took orders over the phone, then made a collection of the requested goods placed in cardboard or wood boxes. High school boys carried the boxes to vans or station wagons to deliver all around town.

The delivery jobs were coveted by youth because they came with perks. First, one had wheels and one could give buddies rides by little detours. Second, wheels gave you status among the girls, who might just need a detour somewhere, too. Third, there was always some breakage in the store room. More breakage occurred in the cookie collection section than elsewhere, about which the young sales clerks and young delivery boys conspired to know precisely where.

After a short stint helping my brother, the town milkman, deliver by horse and buggy, I was one of those grocery delivery boys who improved his limited driving skills, who hauled 100-pound sacks of sugar or flour into porches and received a very wide range of tips. Two English spinsters insisted I had to come in, sit down and drink tea before they handed over some change for their weekly delivery.

The attitude towards taking time with customers was different then, too, even if the boss did not appreciate it. At the home of an elderly Greek gentleman, I learned about ozo, which came in a tumbler, accompanied by much gracious gratitude.

Like my fellow delivery boys, I came to know many people in the town, as well as who was generous and who was stingy. We knew the customers at the delivery end while the store clerks knew the customers personally at the buying end, so we knew who was fussy and wanted particular brands as opposed to those who let the clerk decide. Pay was once a month or whenever the purchaser made it to town or infrequently by cheque to the delivery boy.

My delivery buddies and I also invented a new winter sport. Since no sand or salt was put on streets and winter tires were not in use, we delivery boys would agree to meet at the edge of town and compete to see how many times we could make our vans turn around on the slippery road.

A preliminary check on the Sudbury situation found the following (thanks to Jason Macron, Marzio Appoloni, Lynn Gainer and Leo Doucet). In central Sudbury, a number of stores (Grace, Orange, Northland) offered home delivery until the 1960s.

According to Lynn Gainer, her grandfather delivered for Grace Grocery by horse and buggy. In Copper Cliff, “Red” Pianosi not only had home delivery until the 1970s, but frequently extended credit to his customers. In Coniston, one grocery store may have delivered until the 1990s.

As well, some butcher and bakery shops did home delivery. To refine details, this subject could be a good research topic for a history student.

The world was different then. Instead of trusting in electronic machinery as now, trust was between people who knew each other and their situations, saw each other at church or in service clubs or at public festivities.

But shopping via phone was second nature to more than half the town as many small local shops packaged and delivered locally. Of course now, it’s impersonal by the big box multinationals delivering by mail and courier. Similarly with the new fad of individual packaged meals by subscription.

We may not want some aspects of shopping from home in the old days in Alberta, which possibly existed in Sudbury. One of my schoolmates ran an overnight delivery service for car parts. You told him what you needed and next day someone in town would be missing that part in their car, but yours was fixed. At the time, a limited number of car models with replaceable parts made this system function.

Similarly with the liquor age at 21, overnight services and home delivery by special courier was frequently used, with “home” being behind the elevators or near the train station or even the bushes near the edge of town.

My elder Sudbury buddies state that they frequented this type of grocery delivery operated by cab drivers and small convenience stores, even the mother of a later mayor.

Whether by phone or online, ordering goods will remain a useful option. But despite what a younger generation may think, it is not a new or novel phenomenon, but like many other aspects of modern life, may have lost some of its rustic charms along the way.

Dr. Dieter K. Buse is Professor Emeritus, History, Laurentian University. He has published many studies on modern European history and more recently on our region, including Come on Over: Northeastern Ontario (co-authored with Graeme S. Mount) and the two volume work, Untold: Northeastern Ontario’s Military Past vol. 1: 1662-World War I and vol. 2: World War II-Peacekeeping (available from Latitude 46, Sudbury). In 2020 the last two volumes won the Fred Landon Prize of the Ontario Historical Society for best regional history published in the last three years.