Niigaaniin Services, in partnership with the University of Ontario Institute of Technology, have published an article in several journals, including the Oxford University Press, detailing research project that the authors hope will form a methodology and model to reshape the way social services like income, health and employment supports are administered in First Nations. Niigaaniin director Elizabeth Richer told Sudbury.com the model is based on a more holistic approach, rather than individual, and one that administers wealth instead of poverty. She said the model removes the distinction between social service client care and community development.

Niigaaniin is a social services organization that began in the 1990s, what Richer calls “the dream of seven communities from Sault Ste. Marie to Sudbury.” The nations, under the North Shore Tribal Council The North Shore Tribal Council First Nations are Atikameksheng Anishnawbek, Batchewana First Nation, Garden River First Nation, Thessalon First Nation, Mississauga First Nation, Serpent River First Nation, and Sagamok Anishnawbek. Together, they are known as Mamaweswen.

At first, said Richer, the focus was on administering family benefits — colloquially known as ‘mother’s allowance’ — before becoming the Family Benefits Office in 2000, finally allowing them to cover more of the communities needs. It wasn’t entirely covering the needs of the community, but better than before.

When a new opportunity came up in 2018, the Guaranteed Basic Income pilot project, it was one that Richer and Niigaaniin wanted to be involved in, especially from an investigative angle. They wanted to be involved in gathering data. But when they did begin to talk about it, they were shocked by the response from the community.

Surprisingly, basic income was not the desired option. Rather than a guaranteed income, under the pilot program that would be $16,989 per year for a single person, or $24,027 per year for a couple, less 50 per cent of any earned income, the community wanted more resources.

Richer said one community member told her, “It’s just throwing more money at a problem; we're not going to have anybody or anywhere to go to or any services to access, but we're going to get more money. I'd rather have people to access with less money.”

Richer was intrigued, thinking that the outcome would have been different. So, she asked more people their thoughts. Niigaaniin got a contract from the provincial government and visited 74 First Nations in Ontario, having roundtable discussions around the question “what basic income would look like in your community?” The feelings were the same, money without resources is not wealth.

To Richer, it comes down to administering poverty versus administering wealth. Currently, systems in place for social services offer money, but not much else. It was especially difficult to be without social services in an area that is resource-rich, but without the riches that should come with it.

That comes down to the Robinson Huron Treaty of 1850, covering most of the Mamaweswen area. Within the treaty, which was used as a template for many treaties across Canada, there is an escalator clause — a clause that was to reflect the riches taken from the land, growing as the resource profits did.

Not only was the annuity not raised the first year after the opening of mines everywhere in 1851, but the annuity was not increased until 1874, despite the economic growth on the land. In 1874, the annuity amount was raised from $1.60 per person to $4 per person. There has never been another increase.

First Nations under the Robinson Huron Treaty won a court case regarding the escalator clause, which is being appealed by the province.

Richer said this was another reason to develop better and more “holistic” social services.

“When you look at the Robinson Huron treaty, we should be the richest people of the land from all the resources that have come out. We need to start looking at what our people need in regards to economics, and then what do they need in regards to that holistic approach?”

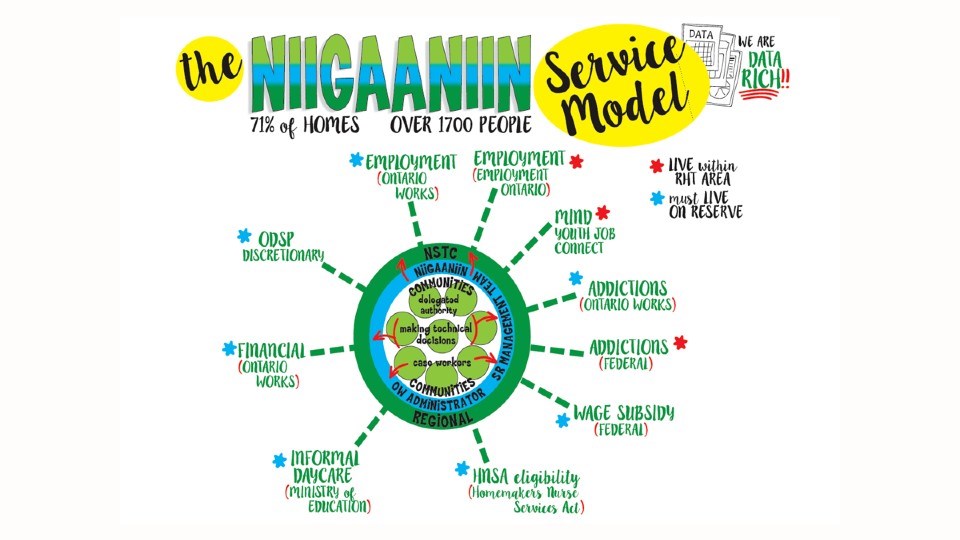

It is also the effects of intergenerational trauma and other issues that aren’t fixed with an income supplement. “That's why we started developing the services that we're providing right now under Niigaaniin and going to Ontario and Canada and saying, here's here's the data that we have, here are the self assessments that people that are administered when when people walk through any of our doors, because every door is the right door. When I look at administrative poverty, I look at that as there's no economic scale in our communities.”

As to administering wealth, that comes with ensuring that everyone in the community has the opportunity to learn and grow as they wish, both culturally and economically.

When Richer presented Niigaaniin’s findings at an economic conference on the subject of Guaranteed Basic Income, the information caught the attention of Dr. Tim McNeill, director of Sustainability Studies for the University of Ontario Institute of Technology. He too was surprised by the findings.

“But I saw it’s (basic income) administrating poverty, instead of really recognizing that there's a wealth of creativity and cultural resources and human resources in the communities themselves,” said McNeill. “It's also admitting, at the same time, that there aren't a lot of resources provided for Indigenous peoples to be administered in this current model, that's just a stark fact of the colonial system in which the social services have evolved here.”

That colonial system differs from the Anishinaabe worldview, in that the first is based on individual needs assessment, and the latter is based on a holistic approach — the whole community's needs are considered.

“With the Robinson Huron Treaty case, wealth that should be in the community, in an economic sense, will be there, and therefore so will the resources to actually administer a way that the community would want,” said McNeill. He said that means material wealth, but also includes recognizing other types of wealth. “To me, it signifies really recognizing the wealth of experiences, a wealth of culture, the wealth of ideas and energies that exist in those communities and recognizing that those are a value and mobilizing, so to speak, to create something better at a community level.”

McNeill, who has worked with Indigenous communities across the world, said he felt the need to set aside traditional economics, like the supply and demand labour model, and begin to see from an Indigenous mindset — starting with the medicine wheel.

“The medicine wheel will have cognitive, physical, spiritual, and emotional elements that are all related to one another, and those elements determine not only how an individual flourishes, but also how they flourish within their community and how the individual makes the community flourish,” said McNeill. “And providing employment stability, emotional help, contact with other humans and meaning and culture, all those things in the community helps you as an individual to flourish as well.”

In talking to the community, McNeill said that Niigaaniin fundamentally changed the idea of social services and individualistic models to one that could encompass the whole community. “You don't just fix an individual and set them out in the same community with employability, what you do is you start community building, cultural revitalization, food security” said McNeill. “You start to create a community in which individuals are embedded, instead of just having a bunch of individuals go through the system and have their money at the end of the day.”

McNeill again states the importance of the Robinson Huron Treaty and the annuities case in the courts right now fighting to have the escalator clause and annuities meet the resources profits taken from the land. “Because the Robinson Huron Treaty was also the prototype for so many different treaties across Canada that followed it, the decision will be precedent setting in Canada; it will set precedent for what will happen with all those other treaties that followed, and were involved in the creation of the Dominion of Canada.”

If that is the case, the social services model developed by Niigaaniin will be beneficial in other communities with treaties as well. “If Niigaaniin has a concrete plan of how to use that (annuity) in ways that actually benefit the community in a culturally appropriate way, especially. That is another model that could sort of sweep across Canada and also be a model for the rest of the world as well,” said McNeill.