By: Norm Tollinsky

“No jobs, no future, no hope” sums up the root cause of the suicide attempts in communities along the James Bay Coast, according to Dr. Murray Trusler, former chief of staff of the Weeneebayko Health Authority.

Although retired and living in British Columbia, Trusler has an intimate understanding of the issues along the James Bay Coast, having served as chief of staff at the James Bay General Hospital from 2004 to 2010.

“Suicide has been endemic (in First Nation communities) for probably a decade and a half,” said Trusler. “When I first started in practice in Norway House, northern Manitoba, we had zero suicides, but we also had an essentially dry reserve. Alcohol was banned … and there were no drugs in those days.

“There was an economy in place. Although they were poor, people were working. They had a commercial fishery. They had sawmills. They were building their own homes. All those jobs have now disappeared. Now, everyone’s dependent on a welfare cheque.”

A similar scenario has played out along the James Bay Coast with the result that there’s no sustainable economy in any of these coastal communities, said Trusler.

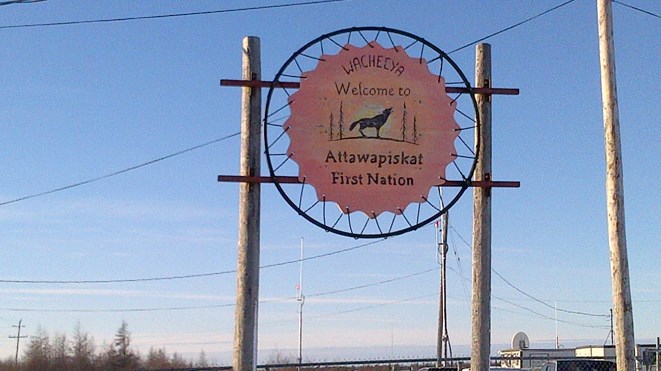

“They’ve lost their traditional way of life. There’s no money in trapping anymore. You used to be able to sustain a small community like Peawanuk on hunting, trapping and fishing, but when you have a community like Attawapiskat with 2,500 people, there aren’t enough animals on the land to support the population.

“Now, they’re forced into buying food at the Northern store, which is beyond most people’s budgets. When I was there, we used to have patients coming in telling us their welfare cheque only lasted for three weeks and they had no food. On some occasions, I would just go to our pantry and give them whatever I had.”

Trusler served as coroner along the coast and investigated numerous suicides.

“Ninety per cent of them were related to drug and alcohol abuse,” he said. “Most of them were males in their late teens or early 20s who had lost a father figure. Either they didn’t know who their father was or their father had left and they were raised by their mothers.

"The majority of them had dropped out of school by Grade 10 and were unemployed, so it’s that demographic that’s most at risk.”

The solutions are multi-faceted, but begin with the construction of 40 kilometres of road to connect Attawapiskat to the outside world and less expensive food, said Trusler. Some fear it would open the door to drugs and alcohol, but drugs and alcohol are already prevalent in the community, “so that’s not an argument any longer.”

Trusler also proposes relocation assistance to help people leave their community — if they want to.

“I had many patients ask me ‘How can I get out of here?’ Often, they were women with four or five children, who saw their community as a dead end. They couldn’t make it on their welfare cheque and just wanted to get out, but didn’t really have a mechanism for leaving, so if Canada can suddenly bring in 35,000 Syrian refugees on an emergency basis, why can’t we provide the same support for Aboriginal people who are stuck on their reserves?”

There’s no disputing the need for a sustainable economic base and the jobs that go with it, but job prospects for people lacking a quality education are poor to non-existent.

“The problem in these northern reserves is nobody’s being educated to a decent level,” said Trusler. “The minute they go outside, they realize they haven’t got the skills they need to get a job. If they do get one, they fall to the bottom because of performance. Then they lose their job and they’re back on welfare.

“It’s unrealistic to think they’re going to be able to put a high school in all of these northern reserves that will meet the standards of high schools outside, so I honestly think they have to face the reality that kids who want a decent education are probably going to have to leave for awhile.

“I also think a lot of these kids could do better if they had a place to study. Most of the homes there are overcrowded. A kid goes home and there are 13 people living in a three-bedroom house. The television is blaring, someone’s drinking in the living room, and there’s no place to do their homework. If they had a youth centre and a place where kids could do their homework, that would be a real help.”

Another solution is home ownership.

“The housing crisis could come to an end if they said, ‘You can own your own home,’” said Trusler. “Like everyone else in Canada, they could get a mortgage from the bank. They’re paying rent now, or they’re supposed to, so the mortgage amount could be the same amount as their rent except now they have a stake in making sure that the house retains its value because at some point they may want to sell it.

"People would also have the option of building a house that’s adequate for their needs and taking care of it. That would create a housing boom that would create jobs and give people hope.”

Last but not least, it’s time for Indian Affairs to wind up, said Trusler.

“I don’t see any future for Indian Affairs. All the services they provide except for land title issues can be provided by provincial governments to a much higher standard. It doesn’t matter if it’s health care, education, justice, policing, infrastructure, or building codes, the feds should get out of the business.”

Flying up mental health counsellors to Attawapiskat as a response to the recent rash of suicide attempts has merit, but “that’s just a band-aid measure,” said Trusler.

The real solutions, he said, don’t have much to do with health care at all.