Sodium Chloride. Or simply, salt. For those with high blood pressure, it’s a trigger. For a chef – it transforms. But for aquatic life, it can mean a death sentence.

A report recently released by the Greater Sudbury Watershed Alliance (GSWA), detailing a study initiated by the Minnow Lake Restoration Group, showed that levels of sodium and chloride in the water are climbing high, and quickly. But it can be hard to really understand what those numbers mean without context, to see the effects of the rise – and what a continued increase will do to our City of Lakes.

So, what does excess salt in water mean – truly?

Human Health and Sodium

The danger of the rising salt levels when it comes to the human population comes from sodium – that wonderful seasoning, and potential health threat.

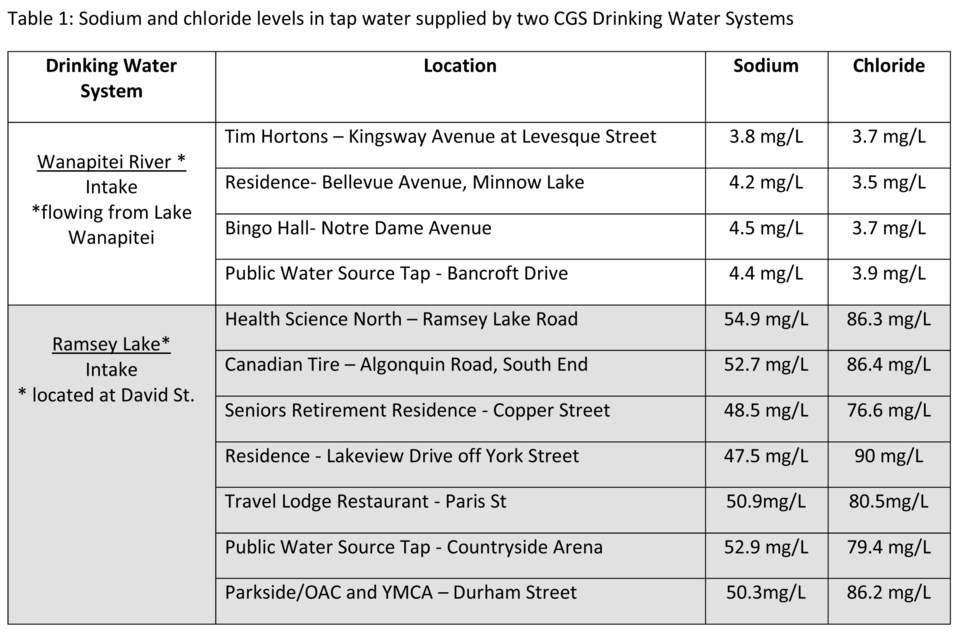

The measurements from Lake Wanapitei — which would serve Wahnapitae, Coniston, New Sudbury and parts of downtown and Garson — are well under any alerts that need to be sent. However, those from Ramsey — the lake that supplies the South End, West End and some of downtown, about 40 per cent of the urban water supply — are alarmingly high and required a notification of the medical community. This is where Public Health Sudbury and Districts comes in.

Burgess Hawkins, manager of environmental health for the health unit, said that because the sodium level as it is isn’t a concern for the general public, they work directly with health care providers to ensure that they can best help those on salt-restricted diets. This type of diet might be prescribed for someone with severe kidney or heart issues, so alerting medical professionals helps them work with patients in these specific circumstances.

This alert needs to be sent when the sodium levels in water reach 20 mg per litre. For the rest of the population, the salt level is based on taste.

“The way it’s written in the legislation,” Hawkins said, “the limit for salt in the water is 200 parts per million (200 mg per litre), that’s under the drinking water standards. Now that is an aesthetic limit, that’s for taste. At 200, you’ll taste the salt and it’s not going to taste good.”

To give the general population a better understanding, it’s good to know the sodium levels of other foods and beverages to qualify what 20mg per litre means — or 50mg per litre, in the case of Ramsey. You can find a full list of comparisons here, but it’s interesting to note that a 250ml glass of skim milk contains 109 mg of sodium; a small bag of chips contains approximately 229 mg of sodium.

In order to reach the worry point for the average person, you would need to drink a few litres of water before reaching a level that could contain more sodium than a cup of milk. Of course, if the levels continue to rise, that could change. And it can’t be good that the current levels at Health Sciences North are 54.9 mg per litre.

Environmental Health and Chloride

It is the environmental aspects of the salt levels that begin to really sound alarms, not just for those interested in preserving the environment, but anyone who loves to play on Sudbury lakes in any season – or have clean water to drink.

It all comes down to algae, and creating an inhospitable environment for creatures who love to eat it.

It’s a problem that creates a cycle. As with any ecosystem, you change one aspect too greatly, you crash the system.

Dr. John Gunn, director of the Vale Living with Lakes Centre, said the main issue with the high chloride levels in our lakes is the damage it does to a tiny zooplankton called ‘Daphnia.’

“The way I describe zooplankton to people it’s the smallest of the animals that are in the water,” Gunn said. “They have brains and stomachs — when you look at them under a microscope they’re kind of cute little fellows — but they are the lawnmowers of the lake, and they are vegetarians, so they’re always eating algae and keeping the water clear of algae.”

But unfortunately, Daphnia and other zooplankton are very sensitive to chloride in the lake, and cannot survive, let alone manage the system.

The Canadian Water Quality Guideline for chloride levels seeking to protect aquatic life is 120mg per litre.

Ramsey has hit averages of 90 mg per litre, and Nepahwin and Minnow Lake, from their surface water testing, have gone higher than 150 mg per litre.

Once the Daphnia die-off begins, the system crashes.

“When the algae is not grazed or eaten by the zooplankton, not only are people going to get irritated because they can’t see their feet and the rocks get slippery, but as the algae dies off, it sinks below the thermocline, which is the stagnant bottom waters of the lake,” Gunn explained.

The rotting algae uses up the oxygen at the deepest parts of the lake, which results in a chemical change in the bottom areas such that phosphorus — which is the main food of algae and normally stays locked up in the sediment in the bottom of the lake — is freed from the sediment and gets into the water.

“And it just starts the whole cycle going, and faster and faster,” Gunn said.

That new phosphorus feeds the living algae at faster speeds, and if you no longer have the daphnia to eat it, it rots and begins the cycle to create more phosphorus.

What loves phosphorus? Cyanobacteria, blue-green algae, a type of algae that produces toxins that are poisonous to humans and other animals. There goes summer in Sudbury.

What’s more, not only do plumes of algae make it difficult to enjoy the water, Gunn also said a study from Maine showed for every foot of clarity lost in a lake, property values dropped $200 for every foot of shoreline.

Challenges Ahead

Sudbury faces its first challenge because of the city’s unique landscape, and the damage once done to it.

“It’s particularly interesting if you look at the story of Sudbury and its land degradation,” Gunn said. “Because we’ve lost so much soil and we have very few wetlands and spongy surface soils left, any amount of salt we add to the landscape makes its way across the rocks very quickly into the lake, so that again makes us even more vulnerable than other communities.”

Salt also can’t simply be removed from the water, or channeled away from the lake before it mixes in.

“Water treatment methods that can be used to remove sodium are reverse osmosis, electro dialysis or distillation,” said Julie Friel, a wastewater legislative compliance supervisor for the city. “These methods are economically unfeasible since the energy and money requirements to operate are high.”

What about the beet juice?

And at the moment, it doesn’t seem like changing de-icing material is the best plan either. Not only would it require testing, the other cities that have implemented de-icing materials like beet juice or cheese brine have had some issues.

In Montreal, for instance, beet juice was tried in a few burroughs, but the overpowering odour put people off and led to a stoppage of its use.

Both Gunn and Richard Witham, chair of the GSWA, said the problem isn’t really with the City of Greater Sudbury’s methods when it comes to salt use. In fact, the GSWA reports the city is abiding by the best practices for roadways.

The excess, in their opinion, is from smaller, unregulated, private parking lots and driveways.

The city’s drainage engineer, Paul Javor, said, “Properties greater than one hectare are considered as a significant drinking water threat if they handle and or store road salt under the CGS source protection policy. This is determined by the Clean Water Act (part IV). Under this legislation lots under one hectare are ranked as ‘moderate’ or ‘low’ threats and risk management plans are not currently being negotiated.”

But one low-risk parking lot added to the hundreds of low-risk parking lots around the city, and the salt really adds up. Especially with the improper use of salt.

Though the city has tried to engage private contractors in its Smart About Salt Workshops – with EarthCare Sudbury hosting the next event ‘Hold the Salt’ on March 25 — the sessions haven’t been well-attended by contractors.

Add to this a desire to avoid liability, and you have the application of salt both when it won’t work, like on uncleaned areas or at temperatures lower that -12, and in amounts that come from the notion of ‘adding more, just to be safe.’

Salt Solutions

Whether it is the sodium or the chloride that worries you most — whether that is for your health, the environment or property values and salt-eroded infrastructure — there is a need to change current practices. That starts with not only acknowledging that every storm drain in the city runs into a lake, but also that you can be ‘Smart about Salt’.

This change to behaviour can also mean that new materials and extreme practices are unnecessary because less salt is applied, and done so with a mind to when and where it should be applied.

If you are interested in finding the best practices when it comes to salt application, to do your part to keep salt out of Sudbury’s lakes, you can find more information here, or you can attend the Troubled Waters Forum on April 30 at Science North, hosted by the GSWA.

There is an absolute need to monitor and reduce the salt in our City of Lakes; this current report shows that while levels are high, they are not unfixable. There is still time to act, but it must be done quickly, because when it is too late, we’ll become the City of Algae. Not the Big Nickel, but the Big Stink.

Jenny Lamothe is a freelance writer, proof-reader and editor in Greater Sudbury. Contact her through her website, JennyLamothe.com.