The skilled trades labour shortage is the greatest obstacle holding back the northeast's construction industry, says the executive director of the Sudbury Construction Association.

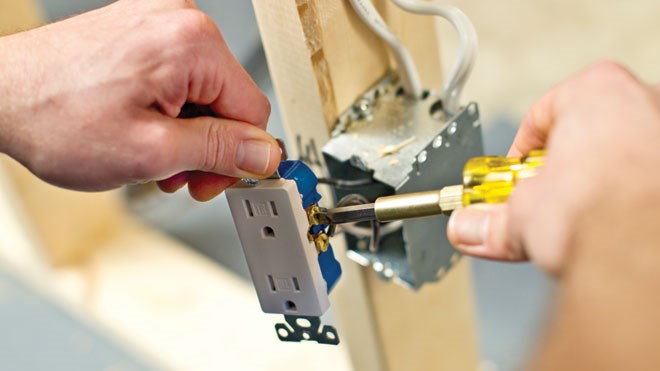

“Some of our tradesmen are making six figures, but nobody seems to want to go in the trades,” said Denis Shank. “We have a huge shortage of electricians and carpenters.”

In a recent report, the Ontario Construction Secretariat found 91 per cent of contractors in Northern Ontario reported a shortage of skilled workers, compared to 67 per cent in the Greater Toronto Area.

The secretariat hired the polling firm Ipsos Reid, which surveyed 500 commercial, industrial and institutional contractors across the province about their confidence for the year ahead and the issues they face.

Shank said many of his members have to decline contracts they would like to apply for, but can't, because they don't have enough skilled workers to complete the work.

He commended Sudbury's colleges – Cambrian and Boréal – for their efforts to promote the trades as viable career options, and their skilled trades programs, but said both are limited in what they can achieve.

To offer a specific trades program, a college must make a training delivery agent application to the Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities.

Because of those regulatory requirements, Sudbury doesn't have a mechanic program, for example.

Shank said the nearest centre where would-be mechanics can be trained is in Sault Ste. Marie.

Other programs, he said, are only offered in the Greater Toronto Area. When students from Northern Ontario complete those programs, he added, they often don't return.

“The further you get from Toronto, the more pronounced the (skilled trades) shortage is,” said Laura Dawson, the president of Dawson Strategic, a firm that conducted a new report, on behalf of several Ontario construction associations, on the gaps in the province's skilled trades and apprentice training system.

One problem, said Dawson, is that the Ontario College of Trades – a regulatory body established in 2009 – requires compulsory certification for certain trades, which limits the number of people who can enter them.

The College of Trades says the review of a trade classification is done in an open and transparent manner, and is conducted by an independent review panel.

“Once the review is initiated i.e. a review panel established and invitations for submissions posted on the website, anyone interested in presenting an opinion on the classification of the trade will be invited to make a written submission to the review panel,” said Ontario College of Trades spokesperson

Jan O'Driscoll, in an email to NorthernLife.ca.

While crane operators aren't in high demand in Sudbury, Dawson said the province is expected to be short the 200 to 500 of the tradesmen by 2020.

Most crane operators, she said, are in their 60s, and because the trade requires compulsory certification, the province only graduates 30 crane operators per year – through a single training centre administered by a union.

“We couldn't find any correlation between having more licensing and having higher safety or better outcomes,” Dawson said.

Removing compulsory certification for some trades would help address the labour shortage, she said.

Independent review panels set the ratios for the number of journeyperson who must be attached to an apprentice.

In 2013, review panels completed their review of all 33 trades subject to ratios, and some ratios were reduced. The ratio review process is initiated every four years, and will begin again in 2016.

A carpentry apprentice, for example, must be trained by at least three journeypeople.

Dawson said in smaller centres like Sudbury it can be difficult for an apprentice to find three journeypeople who can take them on.

“Ontario has one of the lowest rates of apprenticeships in the country,” she said.

Even small regulatory changes, Dawson said, would help address a skilled trades shortage that is only expected to worsen as more trades workers retire.

Join Sudbury.com+

- Messages

- Post a Listing

- Your Listings

- Your Profile

- Your Subscriptions

- Your Likes

- Your Business

- Support Local News

- Payment History

Sudbury.com+ members

Already a +member?

Not a +member?

Sign up for a Sudbury.com+ account for instant access to upcoming contests, local offers, auctions and so much more.