It’s one of those things that happens when it is damp outside. I am pretty sure I have the type of arthritis that gets irritating when the weather is damp. The saying ‘I know it in my bones’ comes to mind.

I haven’t taken it to a doctor because it’s not so bad. But there are days when I feel the ache, especially in my left foot. I was thinking about it recently when I suddenly realized that nearly 40 years had passed since I had the unusual accident that caused this ongoing irritation.

It happened in October of 1981. It was sometime just after two in the morning and I was 3,000 feet underground at the Kidd Mine in Timmins.

I had taken a leave from journalism several months earlier when my salary as a TV reporter had been seriously slashed. A new broadcasting company was being formed with a merger involving Cambrian Broadcasting and Mid-Canada Television. I couldn’t complain. Lots of people had been laid off. In my case, I still had a job, but with a $2,000 pay cut.

With a new house, a wife and a couple of youngsters at home, I didn’t have much choice. I had bills to pay. Mining looked attractive in the sense it paid well.

In those days, if you wanted to work in the mine, you showed up at the mine office and applied for a job. I was given a slip of paper and told to get a chest Xray and a physical.

The day after that I was in the mine captain’s office for a quick interview at 7 a.m. I was given boots, a safety belt, coveralls, safety vest, hard hat, safety glasses, Rastall wrench and work gloves.

I spent the rest of the day in a classroom in the basement of the administration building at the Kidd Mine, getting orientation and safety briefings.

I was with two other guys, Boris and Danny, also starting their first day at Kidd. They had both worked at other mines. The orientation seemed boring for them. I was a stone-cold rookie. I hung on every word the instructor talked about.

The next day I was in the dry where I put on my mining clothes. Everything was new. Everyone could see I was the rookie. Crisp, clean, dark green coveralls.

I looked around and took cues from the other guys. I rolled up the sleeves of my coveralls a couple of turns at the cuffs, just enough to look cool. I tucked my gloves into my belt, wore my hard hat at a bit of an angle and wore my cap lamp loosely dangling with the cord hanging around my neck.

I had been told it was a serious sin to wear your cap lamp on your hat when you got on the cage, because it would shine into the faces of other miners. You just didn’t do that.

The cage was the name given to the massive two-deck elevator that travelled up and down the 5100-foot mine shaft. At Kidd No.1 Mine, the cage carried 140 miners; 70 on the upper deck and 70 on the lower deck.

The cage tender called out the mine levels that determined whether you were upper or lower deck. I noticed many of the miners would walk onto the cage and then turn and face the cage door. That’s because once the deck was loaded with miners, you were squeezed tightly shoulder to shoulder, often so tightly that you could not turn around.

I stuck close to Boris and Danny, taking my cues from them. Don’t make eye contact with anyone you don’t know. Listen for your number.

“Hey Gillis, seven-oh-five-nine. Follow me. We get off at 800, first stop.” It was Ron, our common core training guy. I couldn’t move. I was wedged in too tightly with guys on either side of me.

I hadn’t noticed how fast the cage was moving, but I did sense it slowing down in the darkness of the shaft. Noise and light suddenly washed into the cage. It was the 800 level. There was the overly loud hissing of compressed air and the roar of ventilation fans. The light was the brightness of the shaft station with a dozen bare light fixtures. The walls were painted white, punctuated with rusty-coloured rock bolts holding back the black and grey slabs of stone overhead.

As people began moving off the cage, I was able to walk forward into this bizarre new world. And so it was for the next six weeks that Ron would school us in the skills of hard rock mining; jackleg drilling, stopers, rock-bolting, slushing, mucking, blasting and scaling. Most days we would start off in the 800-level classroom with a coffee break and then head out into the drifts and crosscuts (tunnels).

Fast forward several months later to Oct. 5, 1981. I arrived at work just before midnight. Like everyone else, I changed from my street clothes into my mining clothes. I went to the “wicket,” a long counter area that had little booths where each shift supervisor met each of his miners and gave them their work orders.

On this day, I would be assigned to the 3,000 level instead of my regular work area, which was 2,800. That meant I would ride the cage to 2,800 and then ride a tractor or walk down the ramp to the 3,000-level lunchroom.

In those days, every miner began his shift with a coffee break and there would be no further breaks until lunch. That way you didn’t have miners stopping work a couple of hours into their shift to return to the lunchroom for coffee.

The 3,000 lunchroom was basically a cave cut out of the rock off the main haulage tunnel with electrical lighting and a steel fire door. I was pleased to be there to have a coffee and a cigarette.

That’s when I met my two work partners, a couple of veteran miners, known as ‘drifters’. On this shift, we would be installing heavy electrical cable in the main drift. John was the lead man. Albert was on the five-yard scooptram. I was the helper or “gofer” guy.

As we had our coffee, John outlined the job. We had to install several hundred feet of armoured cable, about three inches thick, along the roof, or the “back” of the tunnel. We would do this by using heavy tie-wraps to connect the electrical cable to recently installed steel guy wire, which was attached to the back by a series of j-hooks. The guy wire was about a half-inch thick.

John explained that Albert would get the big wooden spool of cable, about six feet in diameter, and put it in the bucket of the scoop. John turned to me and said we would need some new scaling bars. We all agreed to meet in the main drift several minutes later.

I headed off to what is called ‘storage’, which is the area on every mine level where you can pick up supplies, such as rockbolts, ventilation pipe, drill steel and scaling bars. That’s where I found three brand new six-foot long scaling bars, which are 7/8-inch steel bars that are sharpened to a point at each end. The points are honed to an almost razor-sharp edge.

Scaling bars are used by jamming the pointed end into little cracks in the overhead rock to pry down any chunks that are loose. In fact, that’s what the broken rocks are called – ‘loose’.

It is everywhere in the mine. You learn to look for it, such as when you walk into a drift and see freshly fallen rock on the ground. You learn to listen for it by striking the back with your scaling bar. A ringing sound tells you the overhead rock is solid. A dull thud tells you the rock is loose.

Scaling is mandatory at the start of every shift. Sometimes it will take 30 seconds to confirm you’re working in “good ground”. Other times it will take 30 minutes just to scale the area you’re working in. Your work area could be 10 feet by 10 feet, but it will take time to scale the back and walls to make it safe.

Even then, there’s no guarantee. Not until you put up screening and rock bolts. Every miner has heard the stories of big pieces of rock that just fall, without warning.

I can recall one day when we were bolting the back. We came across a loose area and began probing it with a scaling bar. Suddenly a massive slab of rock came down right in front of us. It might have been six feet wide and six feet long. The slab was about eight inches thick.

Whump! It landed at our feet.

“Holy sh*t. How thick is that slab?” I asked out loud. “About as thick as a tombstone,” said my partner. We laughed nervously and went back to work.

Back in the drift, John and I began work with the heavy electrical cable. We stood in the scoop bucket on either side of the spool and manhandled lengths of cable, lifting it up to the guy wire. As I held the cable up, John would strap it to the guy wire. Unspool another length of cable and Albert would roll the scoop slowly forward.

That’s when John noticed there was loose ahead. We both grabbed scaling bars and began probing the back of the tunnel. Sure enough, chunks of rock were breaking free and falling. It’s a satisfying thing when you can probe the rock and knock down chunks of loose rock.

At one point, John was leaning far forward, trying to pry what looked like a big slab of loose. I thought, if it suddenly falls, John is leaning so far forward he could fall out of the bucket if the loose falls down. I grabbed John’s belt as he leaned forward. We were about eight or nine feet up above the floor of the drift.

I hollered at Albert to roll forward about a foot. Slow, real slow. Albert was a pro. He could move that scoop by inches. You had to holler. The drift was a noisy place with the sound of ventilation fans and the scoop engine roaring. And hollering meant that everyone else knew what to expect.

Then it happened, all very slowly. I was holding onto John’s belt. The scoop began to inch forward. Slowly. With my other hand, I was holding my scaling bar. I held the bar straight up and down. For some reason I placed the bottom of the bar on top of my left boot. I never gave it a thought. I was watching John pry at the loose and I was watching the scoop inch forward.

I was surprised to feel some odd pressure on my left foot. Then I noticed the bar in my hand was bending. As we rolled forward, the bar had become jammed in the back at one end, and jammed on top of my foot at the bottom end. The bucket was not rising. The roof of the tunnel had either come down a few inches, or the floor of the tunnel had come up a few inches. This all happened in milliseconds.

The pressure on my foot turned into pain. A sharp pain. As the bar continued to bend, I realized the bar had pushed through the top of my boot and into my foot.

I was able to twist my body enough to holler over the back of the bucket to Albert.

“Down! Now! Down, down, down!

The roaring engine of the scoop suddenly died off and the bucket slowly began descending. At this point John turned to me to ask what the hell was going on.

The scaling bar was stuck in my boot. I distinctly remember having to pull the bar upwards to remove it.

A couple of minutes later I was sitting on the ground with John and Albert asking me if I was okay and how did I feel. One of them, I can’t remember who, headed off to the lunch room to call in the accident and pick up the First Aid kit.

The sharp pain was gone. There was only a dull ache. I lit a cigarette. I assured the fellows I was okay and somewhat embarrassed by my actions.

Soon enough, I could see men approaching. I could see the cap lamps in the distance. The shift supervisor that night was well-known by the miners — Kostic Tschop was looking after the 3,000 level. With a name like his, he had earned a nickname: Porkchop.

Porkchop asked if I was okay. He crouched down beside my foot with the First Aid kit. He told me he was going to remove my boot.

“No way!” I said with some force. I am not sure what I was thinking, but I didn’t want to see my foot.

Porkchop said if he didn’t remove the boot right away, my foot would begin swelling to the point that the boot would have to be cut off. It would be messy.

Okay, okay. Take off the boot.

I was wearing a double pair of woolen work socks. On top of the first sock, I could see a hole. There was blood. Maybe a spot about the size of a quarter. Porkchop peeled off the first sock. Oh, oh. I could see a lot more blood on the second sock. When he peeled back the second sock, there didn’t seem to be as much blood on my bare foot, but there was a distinct hole, a dark red hole on the top of my foot.

I lit another smoke. Porkchop applied a bandage. Before long, I was sitting in the tractor as it drove up the ramp and headed for 2,800-station. The cage was waiting. Other miners were there. Guys were acting so politely.

When we got to surface, I was met by a mine security guy with the company ambulance waiting in the headframe. I was strapped into one of those wheeled stretchers and driven off to St. Mary’s General Hospital in Timmins.

The emergency room staff jabbed a syringe full of painkiller into my foot, stitched up the wound, and put on a new bandage. They told me I had some broken bones inside my foot. A tiny piece of bone had pushed through the bottom of my foot. I would have to return at 8 a.m. for an x-ray.

I was back at the mine a couple of hours later. I was brought into the mine captain’s office for the first of several interviews. Other shift supervisors were there, listening in.

I made it clear that I believed this was my fault, that no one else did anything wrong and I was embarrassed by what happened. I wasn’t blaming the mine or anyone else. It was a stupid thing to do and I apologized. I am sure some of the bosses were surprised to hear this.

Some suggested Albert had inadvertently raised the bucket. I said no. When you’re standing in a scoop bucket and it raises, you can feel a little jolt or jerk from the hydraulics. That didn’t happen. As we rolled forward the floor of the drift maybe rose up two or three inches. That way, the whole scoop raised up.

The mine bosses were sympathetic. They said they would send a car to the house every day to pick me up and bring me to work, for light duty in the office. That meant my situation could not be defined as a “lost time” accident. I was fine with it. I still had a job and the pay was great.

I checked in at the mine nurse’s station. Blood was soaking through the bandage and so it was changed. They wrapped a plastic bag around my foot, so I could go through the showers, clean up and get my street clothes on.

Later that morning, I was back in the emergency room at the hospital. I met Dr. Peter Richardson, who inspected the x-ray. He grinned at me and explained I would need surgery and then time off for my foot to heal properly. I told him the mine bosses would be arranging a ride for me to work each day.

Richardson said if I agreed to go back to work like that, I could go find another doctor. So that settled that matter.

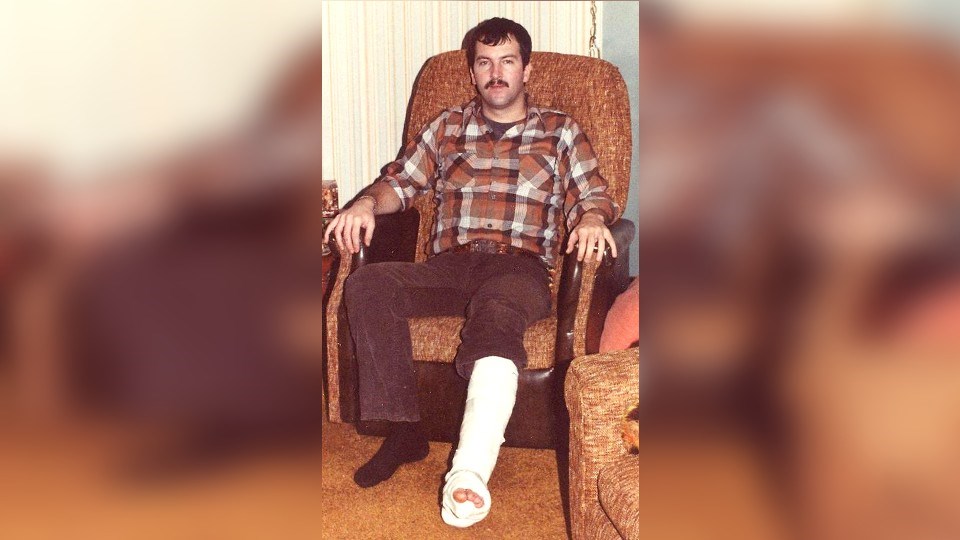

The doctor put a plaster cast on my foot and left leg, and left a hole on the top “for drainage”. It would be the first of three casts, because I developed an infection and then needed surgery.

All in all, my time away from underground was seven months. I healed well and was able to get back to work in the spring of 1982.

I don’t think about it much anymore. Until the damp sets in, that is. Then the ache in my foot transports me back in time 40 years to the days when I traded my pen for a scaling bar.

Len Gillis is a Local Journalism Initiative reporter at Sudbury.com and a veteran journalist in Northern Ontario. He covers health care in Northern Ontario.