Living in Northern Ontario, it can be said that we reside in a winter-oriented area (whether we like to admit it or not) that gives us the benefit of partaking in many various outdoorsy and cold-weather-centric hobbies.

We, the residents of Greater Sudbury, may appear to like our summer festivals exclusively (and there have been plenty over the years): the Northern Lights Festival Boreal, La Nuit sur l’Etang, the Blueberry Festival and many more.

But for me, I say there is naught nor ought there be so exalted on the face of god's white powdery Earth as that prince of outdoor fun, the Winter Festival

For this month’s column, we will take a cursory look at just two Winter Festivals that have taken place in the City of Sudbury over the past 75 years.

In 1947, fresh off the trials and tribulations of the Second World War, the Chamber of Commerce for the City of Sudbury was ready to celebrate winter (and the city itself) with a carnival set to take place in the downtown core.

Throughout the week of Feb. 3, 1947, the city abandoned itself to the carnival spirit. Convention-holding members from the Northern Ontario Outfitters Association, visitors from across Canada and even the United States arrived in droves to enjoy the sights and sounds of the Nickel Capital.

The citizens of Nickel Belt were suddenly brought to the realization their small mining hub town was not only a world-class industrial centre, but also the gateway to a tourist mecca, a winter wonderland for residents and non-residents alike.

And, they all pitched in wholeheartedly to make the event a great success.

It took nerve as well as ambition and imagination for Sudbury to tackle this carnival project on such a major scale. At that point, there was no yardstick of experience to guide the organizers in their work, but they made up with enthusiasm what they lacked in background, and the result was a credit to them and to the city at large.

The official opening of the carnival was presided over by Ontario Premier George Drew. This was followed by a torchlight procession in which thousands of people took part.

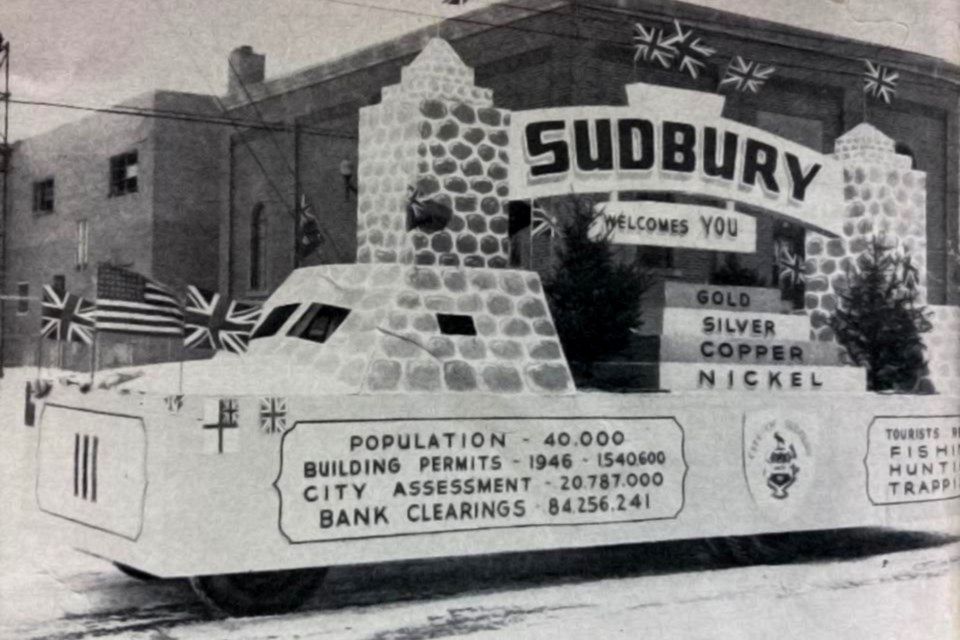

At the end of that carnival week, a mammoth parade wound its way through the city streets with some 70 floats entered, representing a wide range of businesses and groups, including Robin Hood Flour, Levine's, the Kiwanis Club, North American Life, and the New Empire Cab. The City of Sudbury float, featured the heraldic emblem, replicas of the arches that flanked the provincial highway entrances at the time (on the Kingsway and Lorne Street), and local business statistics.

The prize-winning float of the parade was entered by the local Chinese community. It represented an ancient Chinese legend, "The Goddess on the Lily," in which the goddess of mercy, Quan Yen, descends from heaven to bestow blessings upon all girls, and they in turn offer homage for her kindness and protection through the years.

Beyond the parade (which was attended by thousands), the three most popular events were the log sawing competition, a women’s speed-skating competition that drew competitors from across Canada to race on the oval at Queen's Athletic Field, and a ski jump competition that was held near the current location of Adanac Ski Hill.

Held not in some open field or park as would be expected, but right in front of the old Post Office (at the corner of Elm and Durham Streets), the log-sawing championships drew large crowds of spectators. The whine of the large one- and two-man hand saws cutting 16-inch jackpine logs as powerful lumberjacks demonstrated their skill was certainly a novel sound to be heard in the public square of post-war Sudbury.

As for the ski jumping events, it was estimated at the time that 20,000 spectators (remember that Sudbury’s population at that time was approximately 40,000) came out to witness the jumping events of the Ontario ski championships, staged near the current Adanac Ski Hill.

A lack of parking facilities forced hundreds to abandon their cars on the road and trudge across snow-covered fields. Thousands more arrived comfortably on a special CNR train that travelled from the old station located in the now demolished Borgia neighbourhood.

The crowd watched the contestants taking off from a specially constructed tower, and sailing through the air with the greatest of ease.

Even many of the businesses in Sudbury completely enveloped themselves in the themes of the Winter Carnival through decorations on the outside of their locations. Birks-Ellis-Ryrie jewellers on Durham Street constructed an attractive ice palace exterior with colored lighting that turned their business into a quasi-snow sculpture, which was not without a secondary purpose of attracting customers to browse and purchase a gift for a loved one.

At the original F.W. Woolworth location, also on Durham Street, a trapper’s cabin display was constructed in the main showcase window. The two old trappers (which were actually life-like mannequins) in the Woolworth cabin excited the admiration and envy of carnival celebrants. Day after day, they sat in their cozy little shack, “chatting” over a bottle of the finest drink they could get their hands on. They even had a different bottle every day, always empty, but they showed no ill effects (I wonder why).

Unfortunately, this would be the first (and last) large scale Winter Festival in the City of Sudbury for a while. In the meantime, the festival spirit in winter carried on across the Nickel Belt with various playground and service group carnivals, as well as, winter carnivals put on by the outlying communities of Walden, Coniston, Onaping, Capreol, and Azilda (to name just a few).

Now let us fast forward nearly 40 years to a Sudbury that had increasingly changed through the passage of time, many years of labour unrest at the area’s major employer and the coming of age of the Baby Boomers.

At the dawn of the 1980s, a plan was hatched for a major tourist attraction in the city, with the building of a science centre on the shores of Ramsey Lake. One of the lead designers of the project, Raymond Moriyama, described the design concept as “a snowflake falling on a rock”. On Oct. 4, 1984, Queen Elizabeth II officially opened Science North to the public and not four months later, in February, 1985, an annual winter festival designed to attract people to visit our rocky region (just like the Carnival of 1947) was born, the Snowflake Festival.

That inaugural festival, which was designed to boost the image of the city, captured residents in a magical grip they would not be shaken from for many winters to come. This first year boasted 20 different events around the shores of Ramsey Lake, including hockey games, hot air balloon rides, horseback rides, sliding hills and snow sculptures.

After only a single winter, the Snowflake Festival returned in 1986, bigger and better than the previous year, with more of the same events that attracted so many people to the grounds of the newly opened Science North.

The Sudbury Star at the time even referred to that year’s festival, just entering its sophomore winter, as “The Big Daddy of them all.” And, even later that year, after all was said and done, the Snowflake Festival board of directors reported a high profit for what they expected to be a winter tradition for many years to come.

Unlike the Carnival of 1947, which began with a torchlight procession of thousands, each Snowflake Festival would commence with much bigger and more spectacular bursts of flame with a fireworks display to open the festivities and to dazzle the thousands in attendance.

The 1987 festival’s signature snow sculpture event featured an entry by employees of the Sudbury Branch of the Canadian Red Cross that evoked (though not intentionally) the ice palace design at Birks jewellers 40 years before. Red Cross staff put a medieval twist on their ice castle, which included a fire-breathing dragon whose tail was a slide for the children to come out and enjoy. Unfortunately, due to the weather during that festival weekend, this interactive snow sculpture was closed to the public due to being excessively slippery.

By 1990, its sixth year, the Snowfall Festival had become so ingrained in the mid-winter culture of the city that anm attendance record was set with an estimated 25,000 participants enjoying the festival’s Sunday events alone.

During those years on the shores of Ramsey Lake, the Snowflake Festival events were a cross-section of fun for all ages, from minnow races, horse rides and dog sled journeys across the ice and snow to the beer fest where older residents could sit back and relax (just like those “trappers” in the Woolworths display in 1947) chatting over a bottle of the finest drink they could get their hands on.

In 1993, the Snowflake Festival made the move to downtown, returning to the scene of that long ago carnival (at least somewhat in the neighbourhood anyways). The winter celebration would now be making extensive use of the Sudbury Arena, Civic Square, Memorial Park and other locations in and around the city core. The organizers aimed to pump some new life into Sudbury's popular annual winter celebration.

The 1994 Snowflake Festival continued the traditions set over the years, beginning with a bang with fireworks and a torchlight parade (this time on snowmobiles, which weren’t nearly as common during the torchlight parade in 1947). Unfortunately, only indoor events drew big crowds that year. This began the decline (and eventual extinction) of the Snowflake Festival.

In late 1994, the Sudbury Star posited the question, “Would the upcoming winter be the first winter (in 11 years) without a Snowflake Festival?” ringing the initial death knell for the formerly beloved mid-Winter Festival. It would limp along four more winters before being officially turfed by city council in late 1998.

Thus ended another attempt (though admittedly much longer lasting) at a central city winter festival. Of course, that festival spirit (which never really died) once again carried on across the Nickel Belt, with the 2023 Onaping Falls Winter Carnival and Walden Winter Carnival, which are about to begin very soon. And, in keeping with the longstanding winter traditions around the Nickel City, I urge everyone to get out there and enjoy this mid-winter break.

Now, I turn to you dear readers. During this very cold (which was definitely a fixture of many Snowflake Festival years) and snowy week, let us know your favourite memories of the 1947 Winter Carnival, the Snowflake Festival (1985-1998) or any one of the many winter festivals that have taken place across our city over the years.

Were you involved with planning the festival? Were you a volunteer for a specific event? Or maybe just a participant that kept going back year after year for the sheer joy of the Winter Season.

Share your memories and photos by emailing Jason Marcon at [email protected] or the editor at [email protected].

Jason Marcon is a writer and history enthusiast in Greater Sudbury. He runs the Coniston Historical Group and the Sudbury Then and Now Facebook page. Memory Lane is made possible by our Community Leaders Program.