NORTHERN ONTARIO — Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) has announced that the federal government is on track to provide Canadian households access to high-speed internet by 2026.

Recent stats clarify that 93.5 per cent of Canadians have high-speed internet and projections show that 98.6 per cent of households will have access by 2026.

So far, the federal government has invested $3.2 billion in the Universal Broadband Fund (UBF), as well as a $1.2-billion funding program from the province.

ISED states that “up to 75 per cent of eligible project costs (90% for projects benefiting Indigenous communities) are provided to incentivize the building out of high-speed internet connectivity in rural and remote communities.”

Even more optimistically, ISED claims “based on current projections, all households in Ontario will have access to high-speed internet by December 2025.”

Connectivity in Northern Ontario’s rural and remote communities is still feeling the digital divide.

Executive Director of BSEGC Susan Church explains that in areas such as Southern and Eastern Ontario, its terrain is ideal for quick and easy development.

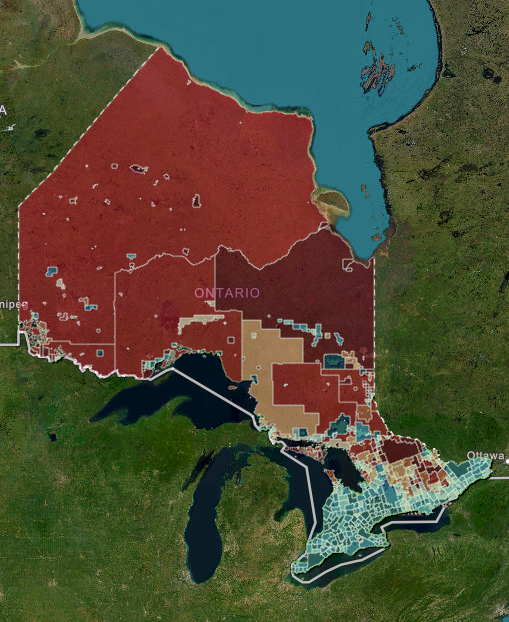

BSEGC is a nonprofit corporation whose role is to support areas of economic development like forestry, mining, and technology. They developed Blue Sky Net as a way to bring the private sector and upper levels of government together to build broadband projects. The Blue Sky Net maps provide their clients with a visual overview of where ISPs could fill the void.

She said, “if you look at the (Blue Sky Net) map and you drill down into the Southwest or Eastern Ontario, indeed, there are pockets and they're working to solve those problems and that's great. But in Northern Ontario, it is a completely different story because of the topography of Northern Ontario. What works in the large vast flat fields of Southwestern Ontario doesn't work in Northern Ontario. and that's the problem. We have literally been begging for funding programs to recognize that they have to come up with a better mouse trap - that it can't be just based on what has worked in other areas.”

Northern Ontario is broken into 12 districts. The Kenora District, the largest of the three districts in Northwestern Ontario, consists of 59 communities. The majority are remote fly-in First Nations. Eight communities out of 59 have 75 per cent of household internet of 50/10 megabytes per second (MBPS) coverage.

The Thunder Bay District has 33 communities. Nine communities have 50 per cent household coverage of high-speed broadband and eight communities have 75 per cent access to 50/10 MBPS.

The Rainy River District has 25 communities. Four have 50 per cent household coverage while three communities have 75 per cent access to 50/10 MBPS.

Church explains that within the data they have collected, therein lies the problem with governments claiming that they are on the fast track to bridging the digital divide.

“The plan is to go to 98 per cent and that's great, but what that still represents is a massive number of people across the country who live in predominantly rural and remote communities - they are the ones that haven't had broadband for a very long time,” said Church.

“When you take out the five or six major cities, it completely impacts the numbers significantly because, again, with that same model, you take out the rural and remote communities and our number in Northern Ontario is extremely low in terms of who has access to at least 50 by 10 (MBPS),” Church acknowledged.

Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellites such as Starlink and Xplore have easier access to the market in far northern communities.

ISED suggests LEO is “often well-suited for areas where installing fibre optic backhaul is prohibitive due to challenging terrain, remoteness and a lack of existing infrastructure.”

LEOs are not easily obtainable due to high start-up costs and monthly fees.

Church claims that the major telecoms and Internet Service Providers (ISPs) find it extremely challenging to turn a profit in small communities.

“It doesn't bring the profit margins that they need to have a robust project. These communities are just left behind,” said Church.

For instance, “Fibre” internet is touted as the fastest type of internet connection speed, providing up to 100 MBPS speeds.

Church explains that because the vast majority of broadband infrastructure is owned by large telecommunication companies, heavily populated areas along railway lines and highways were targeted. In turn, smaller ISPs would fill in the gaps by branching off by connecting to those lines.

“Now, to do that, they have to be able to pay a price that is going to work with their business plan . . . The real need in Canada is to be able to receive a fair quote on taking that 'Fibre' that's needed to backhaul internet networks,” said Church.

She believes the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) needs to look into regulating the playing field for small ISPs filling the gap in the rural and remote regions.

“We're hopeful if we continue a dialogue with both levels of government that our elected officials will take up the fight. We're hopeful because they know, they understand in Northern Ontario, any of the elected officials know just from their own experience, how hard it is to conduct their business. It's hard for businesses to compete globally because they can't have the same playing field as their counterparts in other areas. This problem is not going away and it needs to be solved,” Church stated.