The following is not about the famous last spike, but the (so far) less famous first spike on the Canadian Pacific Railway. The beginning is more important today for Northern Ontario than it was then.

For context, we know about where the the last spike of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) was hammered into the track bed. Canadian historian Pierre Berton wrote about this. It’s that iconic photo of men with long beards, pounding away at a railway spike.

The first spike is also significant enough that, on Tuesday Aug. 15 at 7 p.m., at a special meeting of Bonfield (between North Bay and Mattawa) municipal council, a greater North Bay group, (Fire Up 503) is proposing a multi-million dollar excursion, steam train tourism initiative that will commemorate the beginning of the CPR and the historic first spike. The group has been working on this since 2017 and it pledges to restore Ontario Northland Railway (ONR) steam locomotive #503 which was once a stationary heritage attraction in Lee Park, North Bay.

It hasn’t been fired up in more than 50 years, but the group says, “We're looking to change that by restoring and rebuilding it and returning it to service as a heritage rail attraction.”

“The vision is to create a one-of-a-kind iconic attraction for North Bay with short excursions running in all directions, with an opportunity to bundle a package with tourist operations,” spokesperson Bill Love said.

Now that the line has been identified, it would use an existing Ottawa Valley Railway line anchored in North Bay and could end up at the municipal office and park area in Bonfield some 30 km away. It is estimated refurbishing the #503 locomotive to operating condition would be approximately $2 million alone and it is anticipated a presentation to North Bay city council will follow.

History

Most people are familiar with one of the most historical of Canadian photographs. It pictures a group of railway builders surrounding Donald Smith, at Craigellalchie in the mountains of British Columbia, early in the morning of Nov. 7, 1885. It depicts the driving of the last spike. The ceremonial event allowed the first transcontinental steam locomotive of the CPR to link east with west.

Certainly it deserves as much recognition for initiating one of the greatest construction schemes, while fostering the first wave of Canadian nationalism within the realm of settlers’ heritage.

One hundred and forty one years ago, west of the village of Rutherglen (34. 5 km east of North Bay and 27.9 km west of Mattawa) and near (east of) Trout Pond Road on Highway 17 the first spike of our national railway was driven in the late spring of 1882.

Importance

Elmer Rose is a retired conductor/engineer is a local historian. He is a four-generation resident of Bonfield Township. He explained about the contemporary concept of the steam train and a lot more about the significance of the first spike.

“The Rose clan arrived and ventured up late 1877 by tote road and pair of oxen to set up camp, but almost froze and starved to death spending the winter in a tent and cutting beaver grass in the fall along to feed the oxen.”

Rose has undertaken considerable research into the early years of the Bonfield area. Evidence in the Ontario Public Archives supports this important historical fact unfortunately despite the lack of fanfare the CPR gave to the driving of the last spike.

“I have a Nugget clipping describing what Duncan McIntyre thought how it reminded him of his Scotland homeland with the rolling hills and giant trees. He looked back over his shoulder and rolled his tongue naming it ‘Ruther Glen.’ From 1878 -1880 the County of Nipissing shows 50 families, By 1903 Rutherglen hosted 200 in population. Before the trains all transportation was by the Mattawa River, foot, or logging tote roads created by JR Booth. It took my family five days by horse and buggy to reach the first spike location, resting every 14-16 miles for sleep and a cup of tea for five cents a cup from these stations. The building of the railroad work in gangs were commissioned by Duncan, walkers from Sweden, Poland and Finland in place to mark out the right of away, they were experienced bush men with very little tools.”

Records show 750 teams of mules/donkeys, 350 Dog teams and 4000 men worked the roadbed heading west.

A national dream begins

Few Canadian historical subjects enjoy as extensive a bibliography as that of the CPR. This multi-faceted drama, involving the dynamic personalities of many well-known early Canadians, is the account of where and when the CPR started its march westward from a wilderness spot east of North Bay.

The formation of the CPR, with royal assent, was given by parliament on Feb. 15, 1881. The CPR syndicate (George Stephen, Duncan McIntyre, Donald Smith and others) arbitrarily designated its eastern terminus somewhere near the eastern shore of Lake Nipissing. The survey work was not completed, and the eastern terminus was only a hypothetical place in the wilderness.

Railroad construction had been underway for several decades in Ontario and Quebec, including the Canada Central Railway (CCR) which was slowly being built up the Ottawa Valley to a point past Mattawa.

The CCR was owned by Duncan McIntyre and was being financed by government subsidies, which would cease when the CCR reached the proposed terminus of the CPR. John Ferguson, a nephew of Mr. McIntyre, a teenager, delivered mail along the construction route, and dubiously secured the land that would become North Bay.

As work progressed during the years of 1878-1881, Mr. McIntyre bestowed the name of Callander his birthplace in Scotland to the point where construction would stop. There was no reason get there because the location offered no financial incentive beyond what J.R. Booth had envisioned for the Ottawa Valley, this was new territory. Upon selling the CCR, Mr. McIntyre became a vice president of the CPR.

The inside information and the subsequent land tenure secured by the nephew, John Ferguson, was scandalous, no different than Enron in 2000 or the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007-2008. People profiting from an economic situation.

Ferguson purchased 288 acres of land for a dollar an acre and his lot #20 was the first cleared for a town site. He became a postmaster, reeve, member of the Board of Trade, council member, magistrate and was four-term mayor starting in 1919. Contemporaries described Ferguson as "a hustler, an animated steam engine in trousers." (I have explained much of this and more in two of my books, North Words and Boosting the Bay.) North Bay will celebrate its hundredth anniversary as a city in 2025. The largest headstone in North Bay at the Union Cemetery is dedicated to John Ferguson. Many of North Bay’s main streets are named after the McIntyre-Ferguson clans.

The Canadian Pacific Railway beginning

On June 9, 1881, the CCR was absorbed by the newly created CPR. James Worthington, manager of construction for the CCR, was in no hurry to reach Callander, as the CPR was undecided where their westward route would travel. The CCR had surveyed the line to travel south of Lake Nipissing to the outflow of the French River on Georgian Bay.

The years prior to 1882 looked favourable for the new settlement of Nipissing on the South River when it was considered a prime location for a divisional point. One of the government's colonization roads, the Rousseau and Nipissing, ran 69 miles constructed through virgin territory, from Gravenhurst to Chapman's Landing in Nipissing. The road itself would turn out to be a dismal failure, as there was little arable land along it's path. By 1874, Nipissing had a population of more than 300 people and an entire town plan had been surveyed on speculation.

The CPR would have required an extensive detour to reach the south shore of Lake Nipissing through the drumlins and eskers of Chisholm and Boulter Townships, as well as a bridging point across the French River. In addition, the railroads received their land for free, but, if they were forced to go through existing settlements like Nipissing they had to negotiate in and out of court to purchase the land.

Another factor, the Grand Trunk Railway from Toronto had already surveyed the route south of the French River and the CPR wanted to stay away from their major competitor. It was purely a case of economics to choose a route that would bypass such obstacles.

The future site of North Bay was a poor site for a port because of shallow water, but a good location for building railway sidings on the ancient, raised shoreline of Lake Nipissing. Most importantly, the distance of 100 miles for required fuel and water put the location of the "great north bay" of Lake Nipissing as the next major stop.

Leaving Chalk River, the next 100 mile interval bypassed Mattawa, Nipissing and Sturgeon Falls, who had all hoped for the important railway centre designation. No way. These established places were left out. The arbitrary and eventual site of North Bay was uninhabited and located on a low lying wetland.

Another choice

In 1879/80, government surveyor, Sandford Flemming, explored a route which followed the Sturgeon River valley to a point which roughly follows the present day Canadian National Railway line. This was the government's preferred route, but the CPR syndicate thought differently. They envisioned a link to the Great Lakes' steamers at the port of Sault Ste. Marie.

All of these surveys and resulting decisions had an effect on where the CPR would begin. The hardships provided by the Precambrian rock of the Canadian Shield and the need to have an all Canadian line around Lake Superior, required a great deal of soul searching to determine where the line should proceed from Callander.

The company, not the government, changed the route for reasons mainly due to the fear of American competition. A route too far north would allow American railroads to send feeder lines into Canada. Worthington's men, working on the Canada Central Extension as it was called reached the Rutherglen area in the spring of 1882.

Steve Smith another committed community historian describes his passion as being a “history bug,” He said,

“As it stands now, we are not quite sure how Rutherglen got its name except that it must have reminded some passing Scot of 'awa' back hame' and the name stuck. Rutherglen in Scots dialect means 'Reddish valley' and I think the original Rutherglen location resembles that description more than the current one - especially if the trees were clear cut by that time," Smith said. "Pine Lake Road plunges into a valley which must have been visible at the time. The CPR's Eastern Division took over construction and headed towards the north shore of Lake Nipissing. “

“In 2002, Bonfield was inducted into Canadian Railway Hall of Fame as the CPR first spike location but, aside from the local history buffs, outside of this area almost no one really pays much attention. There is no plaque on the side of Highway 17 where the first spike was driven. Every day, hundreds of vehicles drive by and almost no one knows the significance of what they are passing.

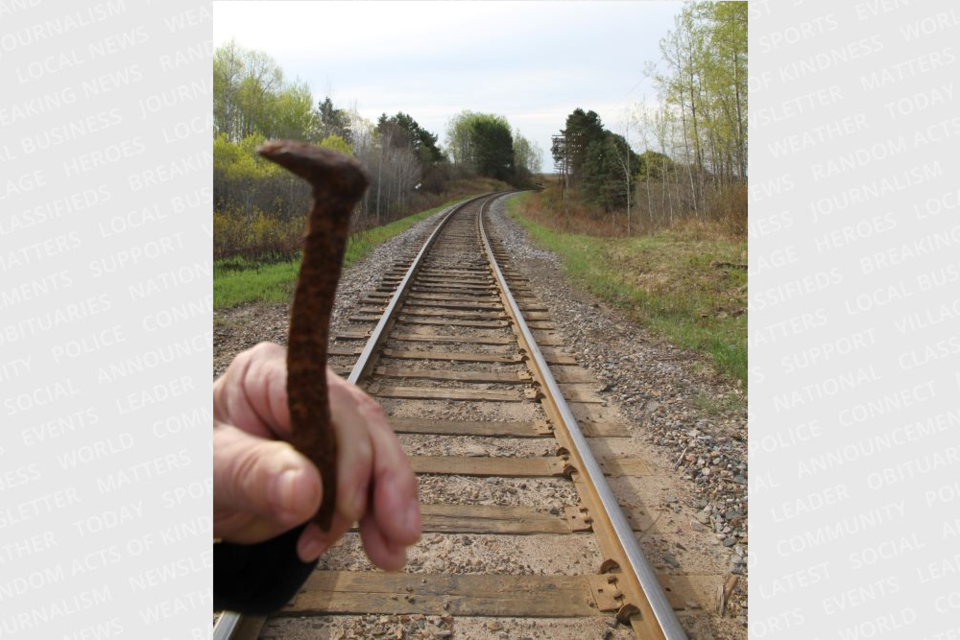

“Like many great moments of history, the first spike must have seemed like a complete non-event to the local people at the time. There was no big photo op with reporters and politicians like the last spike ceremony. If what I've seen of early railroad construction is true, there was no single first spike but likely a dozen or more being driven in unison by a sweaty team of workers. Personally, I kind of like that image one of Canada's greatest engineering achievements being started without ceremony or fanfare. No cameras, brass bands and big shiny hats. There were random working class people, likely of every ethnic heritage, building a railroad in the middle of nowhere with only the black flies and mosquitoes as their witnesses.”

But there may be more fanfare.

You can live stream Bonfield's Aug. 15 council meeting on YouTube live or recorded, see how a rural council works and find out if the first spike will become an attraction.

The original rails and ties have long since been changed, but on a curve near a sand embankment and a wind row of Scots pine is a piece of significant history, including the eventual settling of North Bay. And now there may be opportunity to bring this Canadian heritage vision back to life as a tourist attraction, all on the back roads.