There is the saying: “History repeats itself,” even on the back roads.

This summer we witnessed the devastating wildfires in Alberta and the Northwest Territories. In 2018 there was Parry Sound 33 and the forest fires in the Temagami cluster of parks.

There were three great fires in northeastern Ontario within just over a decade during the early years of the century past. And on your Sunday drives these almost natural disasters are commemorated on several roadside blue-bronze coloured plaques.

Great fires

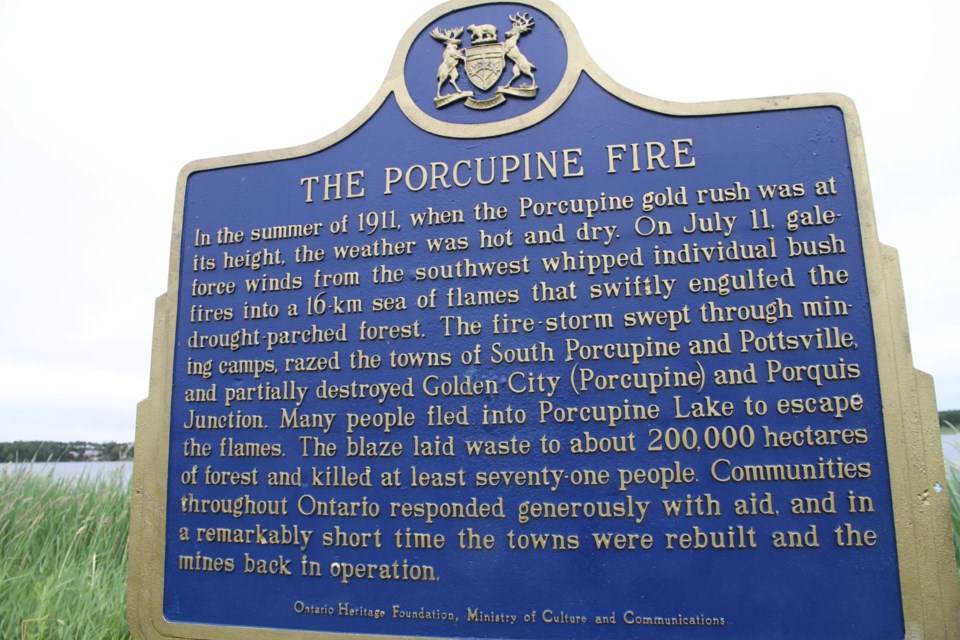

The Great Porcupine Fire of 1911 was one of the most devastating forest fires ever to strike the Ontario northland. Spring had come early that year, followed by an abnormally hot dry spell that lasted into the summer.

On July 11, 1911, when the Porcupine Gold Rush was at its height, high winds from the southwest whipped several small bushfires into flames. The blaze formed a horseshoe-shaped front over 36 kilometres (22 mi) wide. Many people were drowned as they fled into Porcupine Lake to escape the flames, while others suffocated to death underground within the mines.

At one point, a railway car of dynamite stored at the station exploded, propelling the lake into waves three metres (nine feet) high.

The exact number of dead is not known as the region contained an unknown number of remote prospectors at the time of the fire. Official counts list 73 dead, though it is estimated the actual toll could have been as high as 200. The next day the fire swept through the nearby town of Cochrane. The historic plaque is at the Whitewater Conservation Area on Shamrock Ave. South in Porcupine (Timmins). There is also a monolith at Deadman’s Point overlooking Porcupine Lake at the Whitney Cemetery where there are many graves related to the fire.

The great Matheson Fire was a deadly forest fire that passed through the region surrounding the communities of Black River-Matheson and Iroquois Falls, in the summer of 1916.

As was common practice at the time, settlers cleared land using the slash-and-burn method. That summer, there was little rain and the forests and underbrush burned easily. In the days leading up, several smaller fires that had been purposely set merged into a single large firestorm. At times its front measured 64 kilometres (40 mi) across. The fire moved uncontrollably upon the towns of Porquis Junction, Iroquois Falls, Matheson, and Ramore - destroying them completely.

At least 223 people were killed according to the official estimate and remains the deadliest fire in Canadian history. This historic plaque is located on Hwy 101 and Second Ave. in Matheson.

The Great Fire of 1922 was a wildfire burning through the Lesser Clay Belt in 1922.

The preceding summer had been unusually hot and dry. In the fall when burning permits were no longer required, farmers and settlers started to set small bushfires to clear the land. Dry conditions had persisted past the usual "burn" season and on October 4, the wind increased dramatically fanning the flames out of control and combining the brush fires into one large inferno.

Over two days, the fire consumed an area of 1,680 square kilometres (650 sq mi), affecting 18 townships. It completely destroyed the communities of North Cobalt, Charlton, Thornloe and numerous smaller settlements. Englehart, New Liskeard and Haileybury were partly burnt. In all 43 people died. The fires were extinguished when the rain and snow began to fall on October 5. The Great Fire plaque is located just south of Earlton, east side of Highway 11 at the roadside rest stop area.

A comprehensive book on the great fires of Northeastern Ontario, ‘Killer in the Bush’ (1987) was written by Michael Barnes, Order of Canada; one his many books of northern heritage; he was contacted. “The great fires were significant in that there was no fire suppression,” he said. “All they had were shovels. These fires made the government wake up and it led to the creation of the Forest Fires Prevention Act.”

So before this next section a summary for comparison. (Parry Sound 33 in 2018 was 11,362 ha or 28,077 acres.) The Great Porucpine Fire of 1911 consumed 199 915 hectares (ha) or 420 000 acres. The Matheson Fire of 1916, 200,000 ha or 490,000 acres. The Great Fire of 1922, 168,000 ha or 420,000 acres. The causes of these fires can be attributed to people clearing the land. Alberta wildfires in total for 2023- 1,220,000 ha or 3.0 million acres. The size of PEI is 570,000 ha or 1.4 million acres.

The biggest fire

But the largest fire in Ontario occurred in 1948 consuming 280 000 ha or 747 520 acres, half the size of our island province.

I was reminded of the Mississagi fire by Fred McNutt, forester and former GM and President of Wm. Milne & Sons Ltd. sawmill in Temagami.

The new producer of the CBC’s Morning North shared his view on forest fires in this piece. “I was surprised to have never heard of that 1948 fire before, but like most wildfires in northern Ontario (thankfully) it was out in the bush and didn’t really threaten towns or take many lives.

“It was also in the era of mass communication, which was a big factor in those three great fires early in the century, where people didn’t know until it was too late.”

The Timber Village Museum (TVM) is located at the marina in Blind River, this year a new exhibit was launched: Out of the Smoke: Remembering the Mississagi Forest Fire of 1948, marking its 75th anniversary. The exhibit is open until Dec. 31, 2024.

Ashley Young is the manager and curator for the museum. She said, “TVM felt it was an important historic event that not many people know about. As the exhibit was opening, we were feeling the smoke effects from wildfires in Quebec and other parts of Canada. It was quite fitting that we had a display on during this time."

On May 25, 1948, at 1 p.m., aerial forest mapper Holly Parsons spotted a fire approximately 120 kilometres northwest of Blind River, near Peshu Lake. The fire was estimated to be 15 to 25 acres in size. By 4 p.m. that day, the fire had reached 100 acres and it was clear a large number of firefighters were needed.

The fire was finally brought under control in late July but not declared fully extinguished until late August. The Mississagi Forest Fire is still considered the largest forest fire in Ontario’s history.

“The exhibit has been well received by visitors. It speaks to Blind River and area's rich logging history and the effects of the fire on the Blind River Mill. The McFadden lumber mill was once one of the largest white pine mills in all of North America and the devastating Mississagi Forest Fire indirectly led to its closing in 1969. Visitors first learn about the logging operations that were established at the time of the fire, then the timeline and details of the fire, salvage operations, the closing of the Blind River lumber mill, and how the creation of the logging roads during the salvage opened up the area to recreation/creation of the Mississagi Provincial park.”

Watch the documentary

The word implore would be too strong, but you really should consider viewing this vintage twenty-minute documentary. Watch within the first minute or so, how the filmmakers of the time show the extent of the 1948 blaze by burning holes in a map, and listen to the descriptive commentary! Out of the Smoke and its classic footage demonstrates the technology of the day, this is a real learning gem. Watch the use of dynamite at the 17:00 mark. It is spellbinding.

Men were recruited from the street to help fight the fire with the promise of being paid 50 cents/hour and the threat of a jail sentence for not going. Over 1,500 men fought the fire before its eventual end.

The fire denoted the beginning of aerial firefighting, including the use of primitive scoops on airplanes and attempts by pilots dropping paper bags full of water on the flames.

There was also an experiment in cloud seeding, with dry ice to try to encourage rain to fall on the massive fire which in the end only created a slight drizzle.

Post-fire the Ontario government launched a mammoth effort to salvage as many trees as they could from what remained. Operation Scorch employed 2,000 loggers and saved some 300 million board feet of lumber for local mills. Enough lumber to build 16,000 homes.

Fires impact people, property and the environment. With climate change, hot and dry will be the norm and there will be a lot more fires in the future. History does repeat itself, unfortunately, on the back roads.