Each year, I begin my Canadian history course the same way. I get to the classroom 20 minutes before everyone files in, nervously orienting myself before my charges arrive. As the students take their seats, I greet them, but I refrain from divulging too much information just yet.

Once class officially starts, I introduce myself, but I strategically avoid distributing the pile of syllabi I have towering over my desk. This document contains the entire roadmap for the course. It describes where we're going on our journey this semester and the topics we're going to cover, and I don’t want to give it up just yet.

Before we get there, I want to know where my students are in their understanding of Canadian history. Many of them aren’t history majors. In fact, most of them take the course as an elective, and may not have studied Canadian history since high school. As a result, my group usually consists of students with a range of knowledge and opinions on the subject matter they’re embarking upon.

In order to gauge where everybody is in their understanding of post-Confederation Canadian history, I pose to them a simple question. It is as follows, "In your opinion, what are the three most important events, issues, or people in Canadian history since 1867?"

There are no marks for this and it's a completely anonymous exercise, but it gives me some important insights and helps me benchmark the class. I always make sure we do this activity before each student receives a syllabus, that way I do my best to ensure their responses are free from my influence.

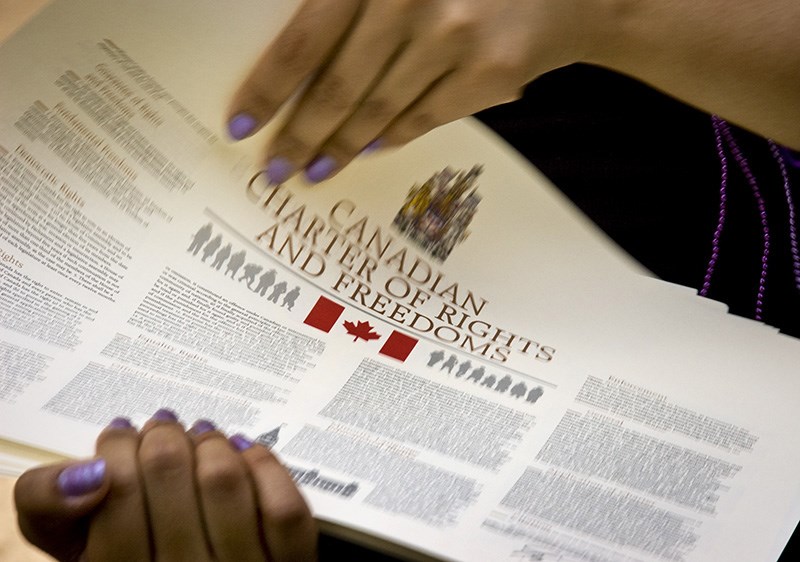

While the composition of my class changes from year to year, the results of this introductory survey are usually the same. More often than not, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms loomed large, and usually has one of the highest response frequencies.

Thirty-five years ago, last week, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was entrenched into Canada’s constitution. In addition, as part of this proclamation, signed by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Queen Elizabeth on April 17, 1982, Canada’s constitution was patriated. Since Confederation in 1867, Britain retained ultimate authority over Canada’s constitution, because our country could not agree on an amending formula.

Even after the signing of the Statute of Westminster in 1931, which gave Canada full legal autonomy, control over the constitution continued to allude our grasp. Finally, in 1982, it was coming home.

It was a significant milestone in Canadian political and legal history, but the most visible aspect of this landmark moment was the inclusion of the Charter in the constitutional package. It guaranteed democratic, mobility, and legal rights, and prohibited discrimination on the basis of a number of factors including, but not limited to, race, ethnicity, sex, and religion.

For many, the guarantees outlined in the Charter have become emblematic of what they believe it means to be Canadian, and for this reason, it merits celebration. Echoing this sentiment on the anniversary, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau issued a statement that said, “The Charter protects the rights and freedoms that are essential to our identity as Canadians. It allows us to express ourselves as individuals and to celebrate our differences, while bringing us closer as a country.”

He also noted that, “for the past 35 years, the Charter has helped build a country where people from all over the world can come together as equals and create opportunities for one another.”

For others, however, the Charter remains a flawed document. Some in Quebec have argued that, with the advent of the Charter, Trudeau changed Canada’s national philosophy, shifting it to one based on liberal individualism and equality.

For them, “it fundamentally altered the nature of Canada by destroying the duality between French- and English-speaking citizens enshrined in 1867.” Partly for this reason, but largely because it was excluded from the negotiation process, Quebec never signed the constitutional package in 1982.

Brian Mulroney tried to bring the province back into the constitutional fold with the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords in the 1990s, but those attempts both failed, and Quebec is still on the outside.

The Charter has also altered Canada’s legal landscape. As part of the guaranteed outlined in the document, the Charter has armed Canadian courts with significant power to challenge legislation from Parliament if it is believed to undermine the rights and freedoms spelled out in the Charter.

According to the authors of the book Narrating a Nation, “Before 1982, Parliament was supreme and it could enact any law within its constitutional jurisdiction – even oppressive ones – but the Charter challenges the supremacy of Parliament and puts significantly more power in the hands of citizens...” Although some might suggest that this isn’t necessarily a good thing, it’s hard to argue against providing the electorate with the greater means to challenge unconstitutional laws.

Meanwhile, others have suggested that, even thirty-five years later, the Charter has failed to meet to its expectations. David Milward, an aboriginal law professor from University of Manitoba, recently noted that the Charter has not had a significant impact on Indigenous communities in Canada.

According to historian Margaret Canada, Indigenous leaders were unable to get the right to self-determination engrained into the constitutional package in 1982, largely forced to settle for the assurance that nothing in the constitution or Charter would undermine “any aboriginal, treaty or other rights and freedoms.”

Writing for iPolitics, Kelsey Curtis and Emma Tranter recently noted that the Charter has also fallen short for Canada’s LGBT community, low-income persons, and women. They noted that, “there is sentiment among charter advocates that the document has not lived up to its promise of equality for women.”

There is much to celebrate with the Charter, but there is also plenty of room to question where the document misses the mark and how we will rectify it in the future. Much like the other events, people, and moments that will be highlighted as part of Canada’s sesquicentennial this year, commemorating the Charter can be a complicated and difficult task.

As a result, it is imperative that, as we continue to celebrate the milestone moments that have happened in our country over the last 150 years, we view these through a critical lens and put them in their proper context.

In honour of Canada’s sesquicentennial this year, Sudbury.com, with the help of our resident historian Dr. Mike Commito, is going back to the archives each month throughout 2017 to highlight some important memories and events in our nation’s history. We hope to provide you with some interesting stories about our past as we collectively celebrate, and analyze, what #Canada150 means.