By Ric deMeulles

If it’s true that every age is saddled with its own particular anxiety, then ours must be the anxiety associated with memory. Newspapers are plastered with conflicting claims about who said what.

Public forums are overflowing with debates about who has the right to remember the past. And when we’re not fretting over public memory we’re silently stewing about the threat of personal memory loss, perhaps considering some miracle tea that’s supposed to keep our memories sharp till doomsday.

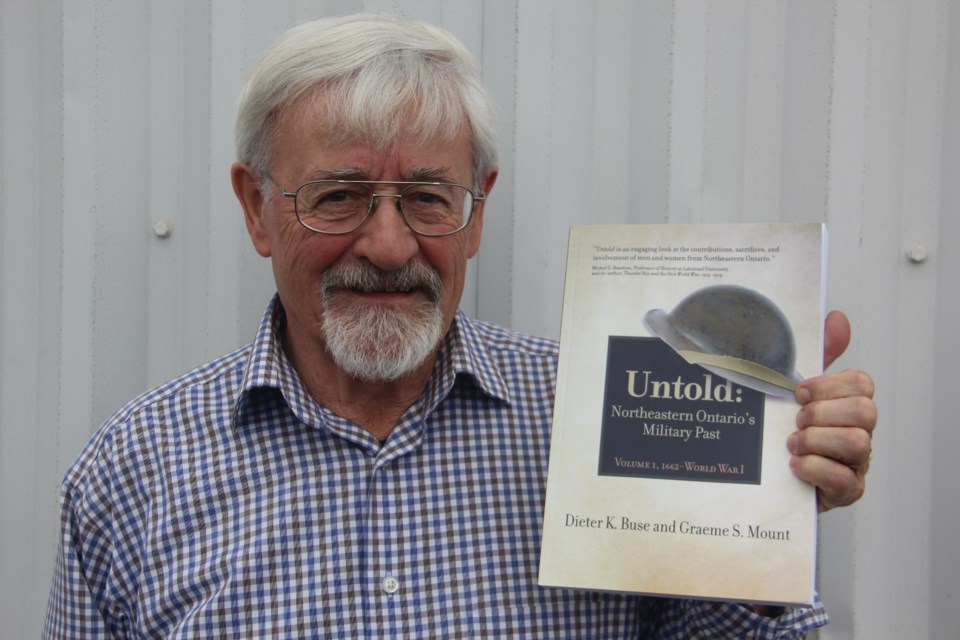

If this is the age of memory-anxiety, then “Untold, Volume 2” (“Untold: Northeastern Ontario’s Military Past, Volume 2, World War II-Peacekeeping,” by Sudburians Dieter Buse and Graeme Mount) is a book tuned to the spirit of our age, dealing as it does with serious questions about war and memory.

How do we produce a collective memory of war? Who gets to say what’s remembered? I know I’m making the book sound as appealing as a bowl of dry Shredded Wheat, but in fact it’s a good read, and as compelling as Volume 1.

Do you remember those stories of nurses tending the wounded amid artillery barrages, of miners tunnelling beneath enemy trenches, of Indigenous sappers crawling through barbed wire? Great stories, weren’t they? Rest assured that Volume 2 is up to snuff.

When I first cracked “Untold” I expected to find it focused on WWII but was delighted to see how much attention was paid to lesser-known conflicts.

There’s the bloody battle of Teruel in the Spanish Civil War, the fighting along the Kapyong Valley in Korea, and the precarious peacekeeping mission on the wind-swept plain of Kandahar, to name a few.

And while I was still revelling in the exoticism of those far-flung locales, I found myself transported to a place infinitely more exotic and remote—the seemingly unknowable past.

Consider this: In the bitter Spanish winter of 1938, a Finnish boy from Sudbury is fighting against Franco’s fascists in the ancient town of Teruel. Seems impossible to understand why he’d have enlisted, and even more impossible to know what he would’ve seen in the ensuing bloodbath.

However, by the alchemy of their craft, Buse and Mount pull back the curtain on the mystery and show us what was going on in the head of this young soldier.

But instead of playing Kreskin, the authors let young Jules Paivio speak for himself. Untold includes excerpts from his memoir, and also includes excerpts from letters home written by dozens of other young men and women.

In one heartbreaking case, you get to read what a young airman says to his parents on the eve of a bombing raid over Bremen, a raid from which you know he will not return.

The story of war is told by a hundred voices. By the grieving mother of the sailor drowned at sea when the Athabascan sank. By the nurse who survived the bloody battle of Monte Casino only to leave her best friend buried in an Italian grave. By the soldier who left his leg in Kandahar, and by the apparently uninjured serviceman unable to outrun the hounds of horrific memory.

Listen to him trying to describe his battle with the demons in his head, “It is not the whole story,” he tells his parents, “for there are many things I have tried to erase from my mind.”

I find the word “tried” gut-wrenching for it implies a failure to find surcease from mental torment. War may deliver us from tyranny but it also delivers us into the clutches of grief, disability and mental anguish.

These stories may not be the usual sort of bromide we’ve come to expect from homegrown histories but Buse and Mount have been careful not to omit such accounts simply because they’re awkward. And that’s what sets Untold apart.

This historical account could very well have contented itself with being a mere compendium of war stories, but instead has elevated its narrative to a critical level in asking questions about war and collective memory. One of these is: Who gets to say what will be remembered? Of course the flip side of this is: What will we allow to be forgotten?

Will we allow some chapters to be cut from the book of collective memory? Will one be the account of how we rounded up and interned Canadian citizens of Japanese, Italian or German descent?

Will another be the chapter on how we labeled soldiers with PTSD as “lacking moral fibre” and then abandoned them? If we’re happy with omitting those chapters, might we decide to exclude others? Maybe we’ll want to erase anything that’s too hard to reconcile.

There’s the rub. Perhaps our anxiety about memory isn’t rooted in a fear of forgetting the past but in a fear of remembering it accurately. And then of having to deal with those bitter bits that are foreign to our saccharine tastes.

Buse and Mount have done us a service in writing “Untold.” Most certainly they’ve uncovered hidden stories, but they’ve also demonstrated that the truth is made up of many small facts, each one needing careful unearthing. But there’s a mischief in their method, isn’t there?

After showing us the hard work that goes into rendering the truth, they’ve placed before us the problem of collective memory. And then poked us with a stick.

Sudburian Ric deMeulles is the author of several books, including “Quinn,” which he penned in 2018. The book is a fictionalized account of the impact of a real-life 1919 event where his grandfather Allan McMaster killed a British police officer in a fight.