There is an immediate and urgent need to change the way Ontario manages the provincial moose population before the resource faces irreparable damage.

Over the past year and a half, I have been communicating with the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry regarding moose management and working with information that was provided under a Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act request, or available from other public documents, especially the 2019 review (1) by the Big Game Management Advisory Committee (BGMAC).

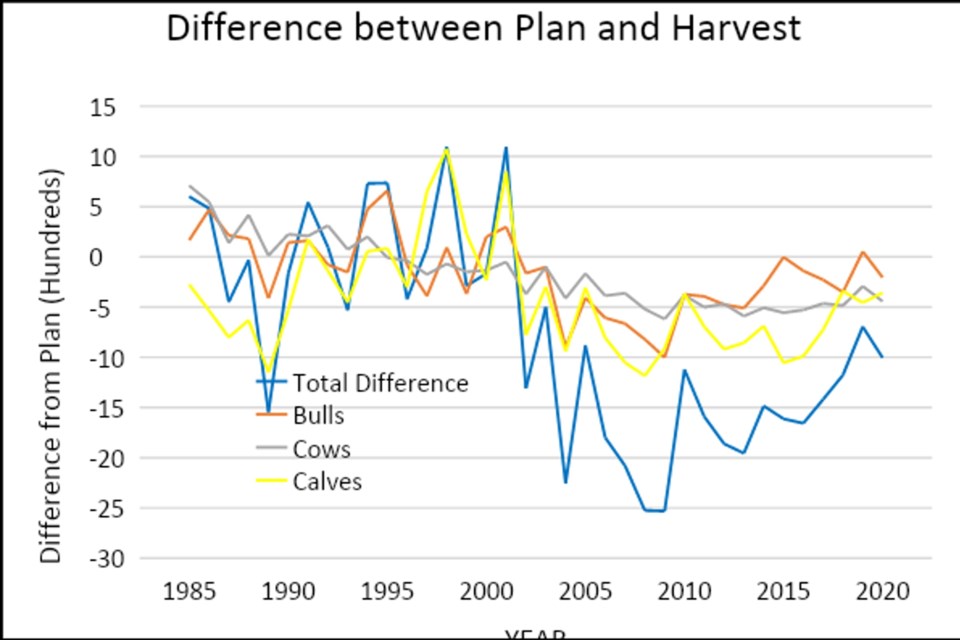

On Oct. 22, 2022, Sudbury.com published an article with unequivocal evidence that, for the past 40 years, MNRF has been planning moose harvests that exceed their own guidelines and permitted harvests that exceeded those planned. Simply put they have accepted and condoned overharvest. This is the most likely reason that the moose population has been declining. It is the only thing that they can control.

The evidence suggests that if the ministry continues with the current management strategy, they risk continued population decline and loss of benefits from moose for decades to come. With closed season, the inevitable result of mismanagement, the population will not increase as it did in the 1950s because there are few refugia from which moose can emigrate (even from parks, because most park populations are low through habitat loss).

I consider the need for change to be immediate and urgent. I can provide other evidence to suggest that the population will never rebuild with the current strategy because of density dependent mortality. Killing success will increase faster than the population can grow.

As I learned of these problems, I brought them to the attention of the acting director of Fish and Wildlife and suggested he pass them on to the advisory committee BGMAC. Since his response was defensive or non-committal, or that as a “director” he didn’t really have a good grasp of the situation, I decided that a direct approach might work better.

I recently provided him with a seven-point plan, that if implemented, should rebuild Ontario’s moose population to levels that are ecologically sustainable through real “adaptive management.” Those words are used on almost every other page of MNRF documents, but I have seen absolutely no evidence that it has been practiced.

There are two important pieces of information from the 2019 review (1) that are very important. They amount to junk science or an intentional effort to mislead the public.

First is the use of management units east (“test”) and west (“control”) of Algonquin Park to demonstrate that controlling calf harvest is important. I absolutely agree with limited calf harvest based on the successful programs in Norway and Sweden. The evidence presented by BGMAC is faulty at best, and part of the conclusion is incorrect. I provided the following feedback to the director.

“BGMAC (2019, p 41) states that ‘generally a % harvest of calves above 20% reduces adult harvest opportunity’, and ‘high % harvest of calves also limits population growth’. They present evidence (p 42 - 45) to suggest that controlling and reducing the calf harvest will lead to population growth. That evidence did not acknowledge the different planned harvest rates between the control and test units. The test units had planned harvests between six and 14 per cent, while the control units had harvests planned between 16 and 20 per cent. All of the units in the test group adjoin and form a relatively narrow band surrounding three-quarters of Algonquin Park. Emigration from the park (Wilton and Bisset 1988) could account for part of the population dynamics. Only two of the control units abut the park and all are generally much further from the park boundary, so emigration is not a factor.

“There are additional aspects to the test units. The population had dropped from about 1,300 moose to 700 by 2002. To remedy the problem, a public advisory group was formed. This group received an ‘education’ from resource professionals. The population was modelled using local and current information. Harvests were set at six per cent and divided equally between rifle and archery hunters. Both mandatory reporting and kill registration were required. The Algonquins of Ontario were fully included in the process, (and) agreed to an allocation of the harvest and reported it. Surveys in 2009 indicated that the population had increased to 1,700. Harvest was raised to eight per cent. The population estimate was about 1,900 around 2013. ”

I subsequently provided the following.

“The 2019 review (BGMAC 2019, p 57-58) presents figures that showed a linear relationship between tag filling rates and the proportion of hunters getting tags. The conclusion was ‘that hunters appear to become more skilled or persistent at harvesting moose’ as tag numbers decline. They also conclude (p 62) that, ‘The largest increase to adult quotas is likely to result from decreasing both the per cent harvest of calves and adult tag fill rates.’ While the second part of that seems obvious from the figure, the evidence for the former is faulty and the management technique to achieve the latter is unclear. I’m not sure how the conclusion on low calf harvest is drawn from those charts.

“There is no effective control on the harvest. Neither hunter numbers nor populations would likely have changed, in fact, moose numbers may have declined. An alternative conclusion might be that ‘the same numbers of hunters were harvesting the same numbers of moose but with fewer tags, resulting in the increased tag filling rate.’ Only when the tag fill rate is 1.0 (i.e., 100 per cent of tags are filled) will there be direct and predictable control.”

I have asked for peer-reviewed papers to support the premise that low calf harvest (in conjunction with higher cow harvests) will lead to population growth. I have not had a response.

This is the plan:

1: In the absence of sound scientific evidence, go back to proven age — sex structures in the harvest — roughly 50 per cent bulls, 15 to 20 per cent cows and 30 to 35 per cent calves. If MNRF really does use adaptive management, they should try different strategies in different Moose Management Zones. I read a recent paper that suggests a “one size fits all” strategy would be inappropriate for Ontario. The only paper I've seen supporting low calf harvest does not directly apply to Ontario, but it suggests that traditional rates are better to optimize the harvest yield, which seems to be Ontario's goal.

2: Get the harvest under control. This chart shows that there is no relationship between tags and harvest. There is no control.

2a: Since the planned harvest exceeds the actual harvest in recent years, let's assume that it is just poor planning. The first step is to reduce the planned harvest at least to the actual harvest. This means a considerable reduction in tags.

2b. Graphs on pages 57 and 58 of the report shows that tag fill rate will increase as tags are reduced. Consequently, Tag Fill Rates will have to be .95 to 1.0 depending on the unit.

3: Return to group applications. I expect they were abandoned because of the abuse of tag transfers. OMNR, with OFAH support, screwed up the original tag transfer policy by letting anyone transfer tags before the season. I wrote the original policy, and MNRF have sort of returned to it with transfers “for reasons that could not have been predicted at the time of application”. OMNR/MNRF knew it was a mess for 35 years and did almost nothing about it. Instead of fixing the problem when it was first discovered, with a proper policy, they ignored it, then abandoned it. With group applications (and an effective tag transfer policy), there will be one application process, results probably by the end of June and all tags issued. I think many hunters already understand and want group applications. In a recent OFAH-sponsored webinar, Patrick Hubert, senior policy advisor, acknowledged there were problems with the allocation process and was looking for solutions. Some 4,500 tags (26 per cent) were not provided to hunters in 2021.

4: Eliminate three application units. With an effective allocation process, proper harvest planning and high TFRs there will be no tags after the first allocation step. Because hunters do not have to claim awarded tags, 10,122 tags (60 per cent) were left for the second allocation step in 2022. In 2021, 4,803 applicants entered the allocation process for their second choice WMU. Of these, 2,654 were awarded a tag, but only 1,573 (59.2 per cent of awarded, 9.2 per cent of total tags) were claimed. Similarly, 4,853 hunters entered the allocation for their third choice WMU. Of these, 1,635 tags were awarded, but only 515 tags (31.5 per cent of awarded, 0.03 per cent of tags) were claimed. I was unable to get comparable figures for 2022 because they weren’t known six months after the allocation process ended. That’s efficiency?

5: Encourage calf hunting by requiring “zero points" to get a calf tag. Tags would be allocated by a draw within units. Hunters would still gain a point with each application until they can get an adult tag. (Calves should provide about 50 kg (110 pounds) of “free” boneless meat.) Since non-resident hunters are not interested in calves, consult with outfitters about giving up some of their calf allocation to residents (not “trading them for adults”).

6: Replace the useless three-WMU hunter activity questions with three hunting season activity questions. With hunters spending different times and seeing different numbers of animals in archery, black powder, and rifle seasons, this would provide meaningful information to support multi-season management. In 1999, I opposed the three-unit questions because they contributed nothing meaningful to management decisions. Nobody was able to explain how it would be used. It has been in place for 23 years. I asked the director, who said, “Whether collecting information from a hunter about one WMU, or up to three WMUs if they hunted in more than one WMU, the information is used in the same way to support harvest plan development“. He could not explain how that was done. Just meaningless words. An average of only 0.25 per cent of hunters hunted annually in three WMUs over the past four years. About five per cent hunt in two units, but this can be assessed by using information from where folks apply for tags and where they state that they hunt most, using only a one-WMU question. Why even that is useful, as hunters move in both directions across units, still escapes me.

7: Work, really hard, to build credibility with hunters and others. I believe this is done with honesty and good management that people can see. It also means admitting mistakes.

The response I got was … well, you can read it yourself.

“I appreciate you sharing your thoughts on the moose management program over the past several weeks, and I certainly respect your knowledge and history of the program. I do want to acknowledge that I understand the concerns you have and appreciate your desire and passion for having a successful program. I have the same desire for a successful program. As this is a relatively new program, the ministry does not have any immediate plans for major changes to it, which you are advocating for. The ministry will continue to consider some minor adjustments to be adaptive to address emerging issues, but generally speaking the changes have been well received and welcomed to support moose populations over the long-term. I appreciate your perspectives and thoughts, which certainly can be considered as part of future changes, but it's not something the ministry is able to implement or change in the short-term. ”

In a different letter, I asked for the land area in the “moose range”. When I was working, that meant WMUs with an open season but excluding the “far north” (true caribou range, WMUs 1 and 25). I was somewhat surprised with the following answer: “Your question is a good one about ‘core moose range’, I’m sure Patrick will have a more detailed response, but generally speaking the ministry refers to Cervid Ecological Zones C and D (and some parts of B as well) when talking about core/main moose range in the province. “

Having grown up in the north, having flown moose surveys across the province and based on my experience with the MNR, Zone B was an integral part of the continuous moose range adjoining CEZ C and D, far more than it was ever a part of the continuous caribou range associated with CEZ A. Perhaps the people of Ontario would be better served if they considered east-west continuity of moose range instead of very dubious north-south continuity of caribou range.

As I interpret his response, the ministry is prepared to ignore a scientifically based alternative interpretation of their own information without even giving it a critical review. Rather, MNRF is prepared to ignore totally what should be essential and urgent change. That the director is prepared to make “minor adjustments to be adaptive to address emerging issues” is hardly “adaptive management”, especially while ignoring long standing and compelling evidence of a major failure to manage excessive hunting effectively. Again, they are using the fact that it is a “relatively new program” to avoid making the hard decisions.

Frankly, I question both his sincerity and his grasp of the reality of the situation.

If he was truly interested in a successful program, he would make a sincere effort to assess my recommendations and provide them to BGMAC. He would resolve the conflict with caribou in WMU 21B. He would ensure that there was adequate public consultation on the Cervid Ecological Framework and Caribou Conservation Plan as written in those documents. He would address the concerns of First Nations and hunters regarding the inclusion of CEZ B as continuous caribou range, in the face of very solid evidence it is not.

He would correct the violation of provincial policy that protected the planned allocation of moose to tourist outfitters. He would invite First Nations representatives to sit on BGMAC.

He states that “changes have been well received and welcomed…”. That certainly isn’t the feedback I’ve heard. Again, this shows that MNRF has its head in dark places and are more concerned with hunter satisfaction than with the declining moose population or the socioeconomic and ecological benefits derived thereof.

Most folks I’ve talked to are fed up with MNRF mismanagement. Hunter numbers have declined from over 100,000 to 41,000 last year. Happy hunters don’t quit hunting. Every single retired MNR biologist I know disagrees with current management practices.

Times have changed, but these are very intelligent and capable folks. The moose population and hunter participation did not decline on their watch.

The fact that a director can dismiss a recommendation for change without consultation, suggests that BGMAC is just a pawn of MNRF staff. They are fed what MNRF wants them to see and expects it to be rubberstamped because they are hunters first.

To suggest that change “is not something the ministry is able to implement…” certainly suggests to me the director has little understanding of what the ministry can do. It appears to me that they (he?) are just incapable or uninterested in making change, even if it is at the expense of the resource and the people of Ontario.

The ministry can absolutely change the age/sex ratios of the planned harvest, and the total numbers of moose to be harvested. That’s the reason “professional” staff were hired. That is not something the public should have control over – or, if they should, then all Ontarians should be consulted, not just hunting interests.

MNRF can change harvest assessment questions and provide “free” (but limited) calf tags without having approval of hunters. They could return to group applications with the explanation that it is better than the inefficient process currently in place – maybe consult with hunters and do it next year. I expect most hunters would appreciate a simpler system. This would solve Mr. Hubert’s problem.

Frankly, I can’t see another solution, but this is not important to rebuilding the herd. If they want an inefficient allocation process, that’s their problem. I don’t think it engenders public confidence in their ability to run an efficient program.

As an aside, there was a study done many years ago that found a large part of anti-hunting sentiments were based in the belief that hunting threatened species abundance. MNRF (and BGMAC) certainly risks inflaming that opinion if it fails to act.

Doing nothing because it is a relatively new program is a blatant failure to even try to fulfill the mandate of the ministry. It is more important to save face than to admit they are doing a poor job and correcting it. That’s about as unprofessional as I can imagine.

I indirectly asked if being a “director” was an administrative role (making sure staff arrived for work on time, chairing meetings, etc.), or a leadership role (ensuring that MNRF are using the best management practices to meet its goals). I believe I know the answer.

Since BGMAC advises the minister, it might recommend that he look for staff who really care about moose, who understand what adaptive management is and who are prepared to act on evidence, not dismiss it because it might be inconvenient to their egos.

It might recommend that he demand that that his deputy minister address the problems identified a few paragraphs above. Some may be above the level of a director. They are all part of the larger moose management problem and require solutions before a moose management program will succeed.

References:

BGMAC (Big Game Management Advisory Committee). 2019. Moose management review. https://www. ofah. org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/MMR-engagement-presentation-May182019-compressed-002. pdf

Alan Bisset is a retired regional moose biologist and wildlife inventory program leader with the former Ministry of Natural Resources. He has written and published many papers on moose management, both Internally and in scientific journals. Bisset lives in Strathroy, west of London, Ontario. You can find his other submissions by typing “Alan Bisset” into the searchbar at Sudbury.com.