BY KEITH LACEY

When Ontario's Lieutenant Governor James K. Bartleman was a child, his family was so poor, he and his three siblings learned to read from comic books abandoned at the town dump.

It might not have been a traditional way of learning, but his love of literacy dates back to learning to read from comic books.

Bartleman says literacy is the key to breaking the cycle of poverty and despair that has gripped so many Northern Ontario aboriginal communities. And it's also the best way to bring together native and non-native cultures to understand and care about each other.

As a child in the 1940s and 1950s, Bartleman's family were considered outcasts in Port Carling because his mother was native and his father was white. But his parents never allowed their children to feel sorry for themselves and instilled pride, a work ethic and love of learning, said Bartleman.

He is grateful that he was encouraged to finish high school and his university education was paid for by a rich American tourist who befriended him when he worked at a Muskoka lodge

After graduating from university, becoming a teacher and then engaging on a remarkable 36-year career in the foreign service, Bartleman was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Ontario in March, 2002.

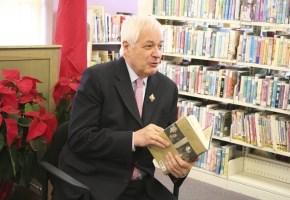

As a guest speaker of Sudbury's Social Planning Council, Bartleman received a standing ovation Monday evening at the Caruso Club, where he detailed his battle to overcome poverty and racism and detailed his determination to be a leader in groundbreaking literacy initiatives.

"We need to give hope to children, both native and non-native, that the world cares about their future," said Bartleman, who visited local schools and libraries as part of a day-long visit.

While the Lieutenant Governor's position is considered a figurehead appointment without significant influence, Bartleman said he decided he'd try to make a difference as the first native person to hold the prestigious title.

He quickly focused his influence on three areas breaking stereotypes related to mental health, fighting racism, and encouraging aboriginal youth to succeed.

Literacy and education are crucial to any kind of long-term success in all three areas, said Bartleman.

Four years after his appointment, the former policy adviser to the prime minister and acclaimed author, is making a distinct difference.

Working with aboriginal Grand Chiefs, universities, colleges, school boards and community leaders, Bartleman is spearheading numerous literacy programs across Northern Ontario and Canada.

He recently launched an appeal to bring books to libraries in native communities with a goal of obtaining 60,000 books. The campaign raised more than 1.2 million books, with 850,000 recently distributed to Ontario's First Nations communities.

His goal is to expand the program to native communities across the country.

He's also established a program where native schools are "twinned" with non-native schools in southern Ontario. Students exchange stories and ideas using modern technology.

He already has 200 schools involved and will also be expanding this initiative.

He's also established literacy and mental wellness camps the past two summers with nine Ontario universities and four colleges on board. This past summer, 36 such camps were established in 28 communities, most in remote Northern Ontario towns.

He has another goal to establish similar literacy camps for aboriginal students across Canada.

Bartleman has also help establish a young readers club in Ontario with 3,500 students already involved. Native and non-native students exchange stories, jokes, puzzles and poems in a newsletter to encourage reading and sharing information to increase awareness of their cultures.

His commitment to literacy programs for both native and non-native young persons will continue after he leaves his office.

During his career he worked and lived in many countries ruled by totalitarian governments, which taught him "life can be very bleak indeed...and people are capable of so much evil," said Bartleman.

As a proud Canadian and aboriginal, he also learned how many good people there are and his job as has been so enjoyable because he meets "only good people."

He's travelled to every First Nations community in Ontario and quickly noticed many southern reserves were well-off and successful, but those in the north "were living in a huge zone of despair."

There was and continues to be an epidemic of suicide among young aboriginals and this breaks his heart, he said.

Lack of educational and job opportunities, combined with appalling poverty, forced him into action.

"How could such a thing happen in this country of ours," he asked rhetorically. "I saw in so many cases a sense of hopelessness."

Join Sudbury.com+

- Messages

- Post a Listing

- Your Listings

- Your Profile

- Your Subscriptions

- Your Likes

- Your Business

- Support Local News

- Payment History

Sudbury.com+ members

Already a +member?

Not a +member?

Sign up for a Sudbury.com+ account for instant access to upcoming contests, local offers, auctions and so much more.