The present discussion about history, monuments and statues is vital. It relates directly to who controls public space and what represents a common past. It points to how a dominant narrative is often proclaimed to be “history,” when in fact it offers a single perspective.

As many have recently learned, much is missing from official versions taught in public schools. For example, a very negative side of Canada’s first prime minister was recently exposed, so honouring him with public statues does not fully represent him or his era, as was and is understood by more critical and thoroughly informed thinkers.

In my view, most existing statues should not be removed, or vandalized. Rather texts with full and fair commentary, including controversial and even conflicting perspectives, could be added. Wrong facts, however, have to be corrected.

A side note: When interviewed by Steve Paiken on TVO’s The Agenda about the two-volume military history of northeastern Ontario that I co-authored, he asked why we included what he called the “dark” side.

He was referring to our documentation of soldiers having visited brothels and contracted sexually transmitted infections (more than 20 per cent during World War I). I explained that well-trained historians try to provide as thorough an accounting of the available facts as possible, otherwise they are creating primarily mythology or apologetics. In this instance, the illness had significant manpower implications, for a sick soldier cannot fight. Hence, he lost pay because he spent time in hospital for what was then termed a “self-inflicted wound” but, most importantly, he was letting his buddies down and crippling the war effort.

Is the present attack on statues of figures with questionable pasts not a result of one-sided, simple accounts glorifying individuals instead of portraying humans with complex traits and motives, including their dark sides? By raising a few individuals to heroic levels, are those raising them not just applauding their own group while denying public space and acknowledgement to others who may have been just as, or even more, meritorious though without the same number of supporters?

Someone recently said statues are the 20th century equivalent of “selfies.”

Let us review the local situation. Sudbury does not have many statues and monuments, though it has some fine ones and a few questionable ones.

Among the best is the realistic representation of Stompin’ Tom Conners. It stands appropriately near the hotels and arena where he frequently played his special form of Canadian country music.

With cowboy hat, boots, guitar, and stomping board, Tyler Fauvelle’s bronze life-size representation celebrates a major cultural contributor with local roots. It might have been erected at the Brockdan Hotel, a place that helped him get his musical journey underway, though that would have been far away from where many people walk and can view the statue.

A positive aspect of this monument is that he is not on a platform or pedestal, because Tom would not have wanted to be set above his audience.

A symbolic representation of the city was created by Colette Whiten and is installed beside the Theatre Centre, with which it is often associated. This statue has silhouettes of people cut out of steel plates.

The motion or drama of good theatre could be read into the plates standing at angles to one another. However, the “Spirit of 83” was actually commissioned by the Chamber of Commerce for $65,000 in honour of the city’s centenary in 1983. This creative and imaginative sculpture is beside one of Sudbury’s busy traffic corners, but increasingly hard to see as it becomes engulfed by trees.

Another Fauvelle sculpture sits at the entrance to the New Sudbury Trail off Lasalle Boulevard. A bigger-than-life otter done in bronze represents nature or, perhaps, the trait of persistence attributed to Canadians.

The Grotto of our Lady Of Lourdes overlooking the rail yards was created by a special interest group of Roman Catholics. Though open to the public, it is private space and used to represent the Stations of the Cross, or where Christ allegedly rested. At one time, the group operating it requested public support, which was appropriately turned down. Unfortunately, vandals defaced many of the harmless statues, which were only partly at odds with others’ historical or mythological understanding while contributing a space for quiet meditation.

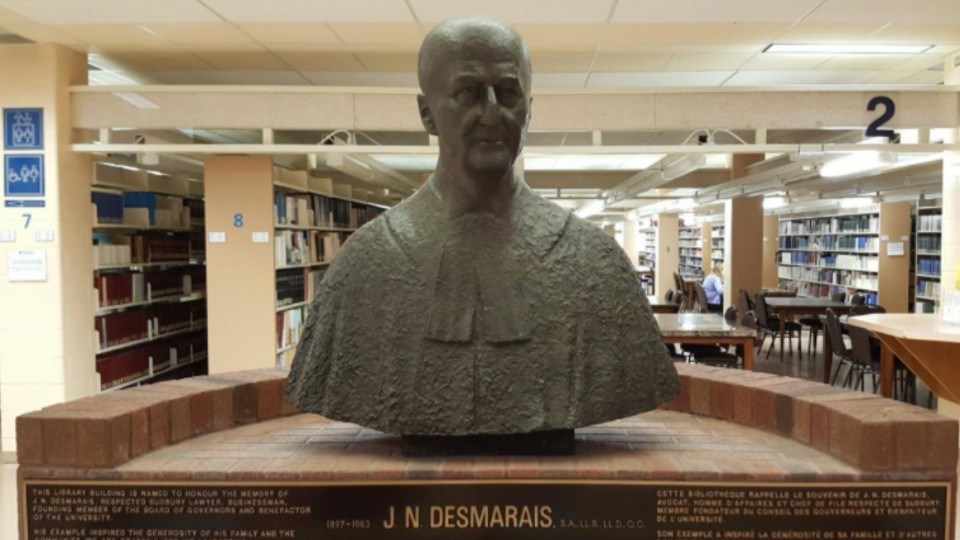

Though the statue of Mahatma Gandhi at Carleton University has come under fire because, in his youth, this advocate of non-violent protest and Indian independence made demeaning and racist comments about Black people, his bust at the entrance to the J.N. Desmarais Library has not drawn much attention.

Another bust inside is of a donor whose name the library bears and has undergone more scrutiny. The family bus company was replaced by a public system because its buses were so decrepit that more than 20 students were hospitalized after inhaling exhaust fumes. Eventually the Desmarais’ company moved to Quebec where the family became multi-millionaires involved in other scandals.

One of the most ambitious of Sudbury’s statues is the Miners Monument, which had to please many interests: unions, corporations and politicians. The work cost $120,000 and the committee was mandated to create a “celebration of Sudbury’s mining heritage” rather than memorializing dead miners.

Some refused to donate because the proposed sculpture did not favour the companies’ outlook. Others refused because no list of those who died getting metals out of the ground accompanied the statue, as had been done in Elliot Lake and Kirkland Lake. The complex statue by Timothy P. Schmalz can be perceived as a depiction of the human and technological efforts involved in getting into the bowels of the earth and the supporting community that resulted.

The location is a problem as the monument is partly hidden away on the west edge of Ramsey Lake where no mining occurred. It would be improved by an explanatory plaque, and perhaps someday a list of the over 600 killed in Sudbury mining accidents will be added.

Sudbury has other monuments such as The Big Nickel or, as someone commented, we like our monuments big and shiny, maybe even in the form of old silos and water towers.

None of the above have caused much controversy, but at least one should.

Sudbury has a legion of military monuments. Nearly every town and village surrounding the larger city has a statue or cenotaph dedicated to the soldiers who fought in Canada’s wars. In the 1920s, most were built to honour the fallen of the First World War. In the 1950s, more were added to include those of the Second World War, and later the Korean War. Notable is that most of these cenotaphs were simple symbolic monuments (without specific statues or names) to acknowledge a serious set of deadly conflicts.

In 2004, a very problematic addition to the series was inaugurated in Memorial Park in the form of a black granite wall with names. The criteria for including the names is unclear, and it seems some names are misspelled and some of the individuals have only a slight association with Sudbury and region.

The main problem is in the identified wars. The monument states that it seeks to “honour members of our community who have died in war or during peacekeeping missions.” The wars listed include the Vietnam War, which was not a Canadian war and in which no Sudburians died. It is a big mistake to include it on the wall, perhaps even an insult to those who served in Canada’s conflicts.

I can foresee the following scenario:

A teenage girl comes home from a school outing to Memorial Park and asks her dad “What was the Vietnam War.” He tries to explain that it was an American mistake attacking a southeast Asian country with bombs and chemicals after the Americans faked an attack on one of their ships in the Gulf of Tonkin. The daughter says: “But it is listed on the black wall in Memorial Park that commemorates Canadians who lost their lives on behalf of Canada.” The father says that is another big mistake and, like other statues and monuments that honour the wrong people and events, it should be corrected. Maybe the Vietnam part could be painted over because it was not a Canadian war and it dishonours those who did fight for their country by being put with others who fought for another country. He adds that he suspects that it is the only monument paid for by public funds in Canada that celebrates another country’s mistaken adventure.

This exchange could take place because school children who go to Remembrance Day ceremonies at Memorial Park (or to Copper Cliff where a plaque makes the same claim) are led to believe that Canada participated in the war and that Sudburians died there.

The Vietnam War claim needs to be removed. If an impetuous person decided to deface what is an historical inaccuracy, would that be wrong or a correction? I hope the city takes the reasonable route to remove the offending mistake to avoid a resort to other means as has occurred elsewhere. As stated above, I would argue that existing statues not be torn down, but that misleading and wrong information be corrected.

Dr. Dieter K. Buse is Professor Emeritus, History, Laurentian University. He has published many studies on modern European history and more recently on our region, including Come on Over: Northeastern Ontario and the two volume work, "Untold: Northeastern Ontario’s Military Past vol. 1: 1662-World War I and vol. 2: World War II-Peacekeeping" (all co-authored with Graeme S. Mount; available from Latitude 46, Sudbury). Buse, as an educator, researches and writes as his social contribution to better understanding the present in historical context.