NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope has revealed the first known system of seven Earth-size planets around a single star, the space agency announced Wednesday.

Three of these planets are firmly located in the habitable zone, the area around the parent star where a rocky planet is most likely to have liquid water.

The discovery sets a new record for greatest number of habitable-zone planets found around a single star outside our solar system.

All of these seven planets could have liquid water – seen as a key factor for life as we know it to develop – under the right atmospheric conditions, but the chances are highest with the three in the habitable zone.

“This discovery could be a significant piece in the puzzle of finding habitable environments, places that are conducive to life,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of the agency’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington, in a press release.

At about 40 light-years (235 trillion miles) from Earth, the system of planets is relatively close to us, in the constellation Aquarius.

Because they are located outside of our solar system, these planets are scientifically known as exoplanets.

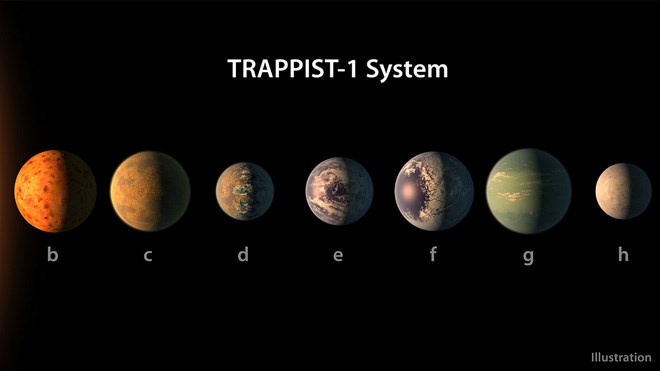

This exoplanet system is called TRAPPIST-1, named for The Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST) in Chile.

In May 2016, researchers using TRAPPIST announced they had discovered three planets in the system. Spitzer confirmed the existence of two of these planets and discovered five additional ones, increasing the number of known planets in the system to seven.

The new results were published Wednesday in the journal "Nature," and announced at a news briefing at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

Using Spitzer data, the team precisely measured the sizes of the seven planets and developed first estimates of the masses of six of them, allowing their density to be estimated.

Based on their densities, all of the TRAPPIST-1 planets are likely to be rocky. Further observations will not only help determine whether they are rich in water, but also possibly reveal whether any could have liquid water on their surfaces.

The mass of the seventh and farthest exoplanet has not yet been estimated – scientists believe it could be an icy, "snowball-like" world, but further observations are needed.

In contrast to our sun, the TRAPPIST-1 star — classified as an ultra-cool dwarf — is so cool that liquid water could survive on planets orbiting very close to it, closer than is possible on planets in our solar system.

All seven of the TRAPPIST-1 planetary orbits are closer to their host star than Mercury is to our sun. The planets also are very close to each other.

If a person were standing on one of the planet’s surface, they could gaze up and potentially see geological features or clouds of neighboring worlds, which would sometimes appear larger than the moon in Earth's sky.

The planets may also be tidally locked to their star, which means the same side of the planet is always facing the star, therefore each side is either perpetual day or night. This could mean they have weather patterns totally unlike those on Earth, such as strong winds blowing from the day side to the night side, and extreme temperature changes.

NASA's planet-hunting Kepler space telescope also is studying the TRAPPIST-1 system, making measurements of the star's minuscule changes in brightness due to transiting planets.

Operating as the K2 mission, the spacecraft's observations will allow astronomers to refine the properties of the known planets, as well as search for additional planets in the system. The K2 observations conclude in early March and will be made available on the public archive.

Spitzer, Hubble, and Kepler will help astronomers plan for follow-up studies using NASA's upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, launching in 2018.

With much greater sensitivity, Webb will be able to detect the chemical fingerprints of water, methane, oxygen, ozone and other components of a planet's atmosphere. Webb also will analyze planets' temperatures and surface pressures–key factors in assessing their habitability.