If you met someone who was afraid of dogs, and when asked, they told you they were bit by a dog and are now uncomfortable with them, you would probably agree that this is the most logical response to the experience. Once bitten, twice shy.

But what if your grandfather was bitten by a dog. Your grandmother, mother, father, aunts and uncles — ancestors going as far back as you can imagine — all bitten by dogs. Your entire nation bit by dogs.

How deep is that fear now, and what would you do to suppress that fear? To prevent it from taking over your body, mind and spirit?

Too often, said Dr. Teresa Naseba Marsh, Sudbury author and psychotherapist, the answer is substance abuse. And too often, it is inextricably tied to the bite of trauma.

“Nobody sets out to become an addict,” she said. “They do it to numb the pain.”

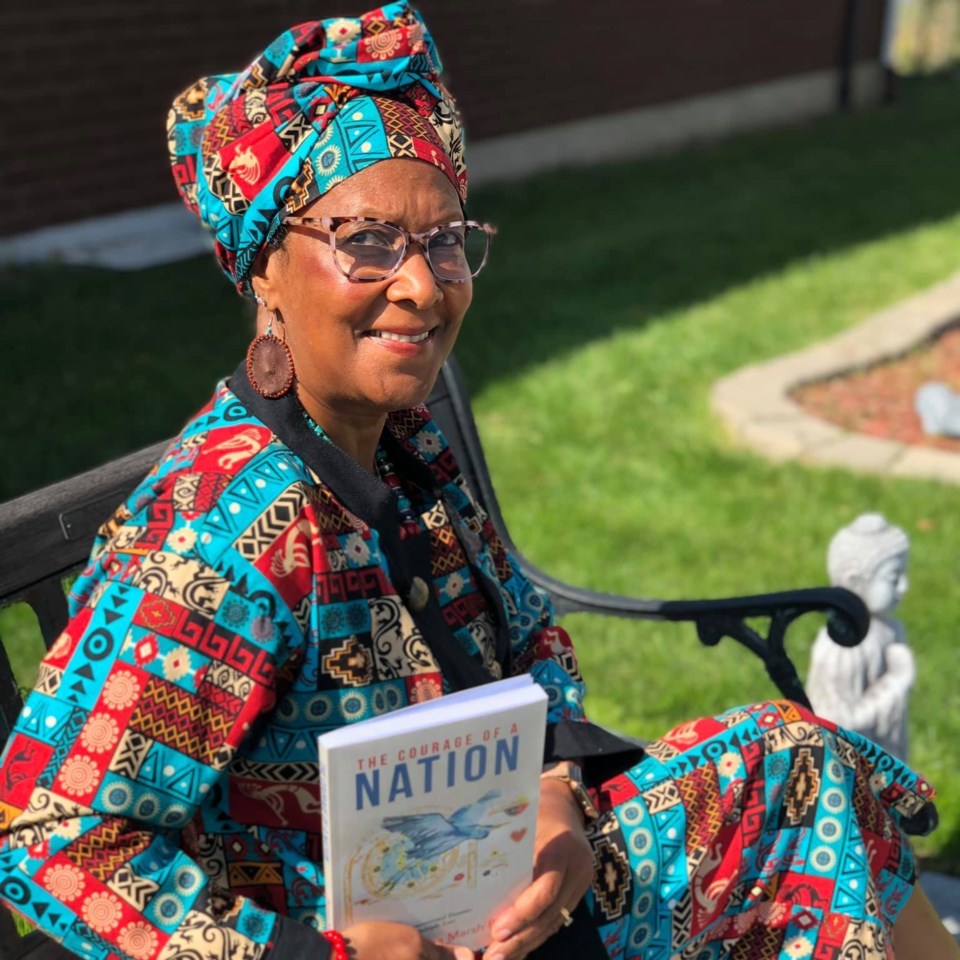

In her recent book, “The Courage of a Nation: Healing from Intergenerational Trauma, Addiction and Multiple Loss,” Marsh offers care models for dealing with substance abuse and what is known as ‘intergenerational trauma’ through an integrated model — without separating one from the other and treating them as disconnected.

Inspired by her visits to the Nuu-Chah-Nulth Nation on Vancouver Island, meeting Elder Allen Dick and the two Nuu-Chah-Nulth communities, Tseshaht and Ahousaht, as well as her experience as a PhD student and working with the Anishinaabek in Northern Ontario, Marsh uses storytelling and poetry, as well as scientific research, to offer a framework to those who seek to treat addiction not as a crime, but as a symptom, a symptom of historic or intergenerational trauma.

But what is historic or intergenerational trauma?

Though the ideas began rumbling in the 1960s, it was clinical psychologist Dr. Yael Danieli that developed the burgeoning understanding. Most recently, she created the Danieli Inventory for Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma.

It was her research that first offered startling findings in the grandchildren of Holocaust survivors.

And it’s important to note the word grandchildren.

Within our understanding of the Holocaust — the event for which there has been the most research on trauma — we have seen, heard and been horrified by the stories of what was done to an entire culture and multiple generations of people, all at once. We can easily understand that direct trauma; its clinical term is ‘collective’ trauma, and it refers to hurt, fear, oppression, domination and abuse that is visited upon a group of people.

We can also easily understand some aspects of intergenerational trauma simply through stories and behaviours. Again to the dog analogy: if your grandfather and father told you from birth that dogs were to be feared, it is likely you would listen.

Historic trauma, too — the idea of collective or ‘group’ trauma that begins to move through future generations. Stories, warnings, even silence can impose fear on those who never experience the initial traumatic actions.

But what about grandchildren of Holocaust survivors? Those who were raised in their presence, but also those who had never met their grandparent? A grandchild who had never heard the first hand stories or felt the sadness and pain of their elder’s experiences?

A field of study called epigenetics, which literally means “in addition to changes in genetic sequence,” focuses on understanding the way the body regulates genes without actually changing the DNA sequence, just the ability to access or ‘turn on or off’ certain aspects of the genetic sequence.

Research says it is turning on and turning off certain parts of Holocaust survivors’ grandchildren’s DNA. Yes, grandchildren.

And historic and intergenerational trauma can be found anywhere there was colonization. From the peoples of Africa, who were enslaved, to the Indigenous people of Canada, this historical trauma response is found around the world.

In Canada, it began with the arrival of colonizers seeking to conquer a new world. But it is more complex than pure evil, Marsh said. For when the colonizers arrived in Canada, not only did they wish to eliminate the ‘Indian problem,’ they also brought trauma of their own. A beaten dog that bites everyone it meets, even those who extend a helping hand.

“When the white men came, the colonizers came in with their own trauma,” March said. “That’s why they were on the ships, why they were sent to Australia, why they were banished. They came with their own trauma. They came with their own shame, and they put it on all the Indigenous peoples across the globe.”

Marsh describes the disorder as an automatic response.

“So once people have been traumatized or they have PTSD, every time they feel all the uncomfortable feelings, their body believes it is still in danger — and the body will stand guard for us. Every time somebody ‘thinks’ they are in danger, the body goes into trauma response mode. The amygdala is sounding the alarm, and it says ‘danger, danger, danger’; you don't have control over it happening in your body.”

Now, that fear and trauma has ripped through nations and generations of people, even to children.

And though the research is early, it’s pointing to a pre-disposition to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Studies testing adolescents between 15 and 19 who had substance abuse problems were diagnosed for PTSD at five times that reported from a community sample. PTSD and Substance Abuse Disorder (SUB) have already been linked.

“It's not the addiction,” Marsh said, “it's about disconnection. When we’re traumatized we get disconnected from our own embodiment, from this vessel. And we stay in the reptilian brain — in trauma response mode — to protect ourselves.”

Reptilian brain is the description used for the basal ganglia and brainstem, involved with primitive drives related to thirst, hunger, sexuality, and territoriality, as well as habits and procedural memory.

And if your body believes it needs to be on guard at all times — red alert as it were — that need to protect ourselves, without the ability to receive nurturing or consolation, drives constant fear. The need to quiet that fear with substance abuse is what Marsh refers to as a ‘warm fuzzy blanket addiction.’

“That warm fuzzy blanket takes this place of nurturing — nobody can live without touch, holding, nurturing each other. But once you start using that (blanket), you become addicted and your brain is just asking for that.”

Soon, it is not so much the trauma driving decision making; it is the addiction. To feed an addiction — the overwhelming and automatic responses from your body you cannot control — one who suffered trauma can then abuse, neglect or impose that trauma onto others. The cycle continues.

As Marsh puts it, “Hurt people hurt people.”

And sometimes, even the grandchildren of hurt people, hurt people.

But she knows there is treatment to be found. It has to happen holistically, and it has to start with asking those who have hoped for a separation from their own mind, have hoped to numb themselves from trauma they experience, heard about, or are suffering the epigenetic results of, to come back into their bodies.

“Come back home to this beautiful body, this container. Because inside of this vessel resides your most precious essence: your jinn, your spirit, your soul, whatever you want to call your connection. And once you come back here, you will need to reacquaint yourself with the language of your own body, because your body's talking to you all the time.”

And it is through her work and writing that she hopes to show others how to do this, to come back into themselves. It takes work, of course, but her experiences, education and teachings from the elders have shown her there is hope.

“If they do the work, they can heal from both intergenerational trauma and substance use disorder. But it's a process.”

For more information on Dr. Marsh’s work and teachings, you can visit her website at TeresaMarshAuthor.com.

Jenny Lamothe is a Local Journalism Reporter at Sudbury.com, covering issues in the Black, immigrant and Francophone communities. She is also a freelance writer and voice actor. Contact her through her website, JennyLamothe.com.