Whenever I find myself downtown, I’m always drawn to the bend where Ste. Anne Road meets Mackenzie Street. Most people tell me it’s solely because of the library around the corner and that I want to go and do research (and they’re usually right). But sometimes I just stand there and admire the brown brick and ancient mortar that make up the remaining part of old St. Joseph’s Hospital, which now is a part of the Red Oak Retirement complex and offers a contrast to its newly built section, symbolically linking old Sudbury Village to new Greater Sudbury.

The early history of Sudbury is inextricably linked to three things: the railroad, the church and health care. This week we will take a look at the creation of what became (and still remains) the longest serving hospital in the city’s history. It is a place where a majority of residents either have a direct experience or a family member that did at some point.

One hundred and forty years ago, this ancient basin of hard rock was an isolated paradise where huge pines thrived undisturbed, weaving a green tapestry across the hills and into the muskeg. Such is the way in which it appeared, in the spring of 1883, to the workers who arrived to lay down the main line of the Canadian Pacific as it carved a route through what was then known as the District of Nipissing.

As the track reached Ramsey Lake, a village of tents and log shanties sprang up almost overnight. Important above all others was a log dwelling some 40 feet by 30, which served as a hospital. It could accommodate 15 patients. Dr. William Howey was put in charge (having arrived just as it was being completed), with his young wife Florence assisting him as nurse.

The nucleus of a settlement was sprouting. The discovery of the vast mineral reserves of the Sudbury Basin led to such activity that by 1886, Sudbury was taking on the appearance of a rapidly growing village. In fact, it grew so rapidly that by 1893, it was incorporated as a town with Stephen Fournier as mayor.

By this time, Dr. Howey’s log hospital had been deemed too small to accommodate the hundreds of lumberjacks and miners who worked across the region. In 1892, a newcomer to the area (weren’t they all at this time?), Dr. Jacob Hart, bought a piece of land situated on Dufferin Street, close to Elm. The small hospital he built was named “Sudbury Hospital.” Within two years, Dr. Hart sold this property to another physician, Dr. John Goodfellow.

On Aug. 13, 1896 (for reasons which we don’t know), Dr. Goodfellow leased the hospital to Father R. P. T. Lussier, the parish priest of Ste-Anne-des-Pins. The lease, which was expected to stand for five years, stipulated that he was to pay in advance an annual rent of $200, one-fifth of which he could keep to defray the cost of essential repairs.

The very next day, three Grey Nuns of the Cross (including Sister St. Raphael, the first Hospital Superior), who had just arrived from Ottawa, entered the Sudbury Hospital to begin their service to the community. With that, the name of the hospital was officially changed to "St. Joseph's Hospital."

Upon arrival, they found three patients, two nurses, two “man-servants”, medicine, cooking utensils, furniture, and 46 beds (with 48 mattresses, 53 pillows and 51 blankets to furnish them).

A recent epidemic of typhoid fever (one of many to hit the area over the years) accounts for the coming of the nuns to Sudbury. Several persons had died due to improper care and Fr. Lussier hoped for the best in entrusting the hospital to the Sisters.

On Aug. 22, Dr. W. H. Mulligan offered his services as the hospital’s first physician for $250 a year. Of the 67 patients treated from Aug. 14th to Dec. 31 of that first year, 63 were discharged with only one death recorded. Fr. Lussier was reportedly well satisfied with the situation.

In October 1896, the municipal council made plans for the town water pipes to be extended to the hospital. This occurred despite the opposition of Dr. Struthers and Dr. Arthur (since they were also town councillors, it’s not surprising), who had their own private hospital on Elm Street (the Algoma-Nipissing Hospital). Fr. Lussier lost no time in immediately fitting up toilets and bathrooms on the first two floors of the hospital.

Everything was running smoothly when, on Jan. 2, 1897, a bailiff arrived at the door with orders to seize 38 furnished beds in order to cover the $215 in interest due by Dr. Goodfellow on his $2,000 mortgage of the property (clearly, he wasn’t a good fellow).

By the 29th of January, an auctioneer was on scene to proceed with a sale of property. However, due to an absence of buyers, the sale was postponed to Feb. 19. This time again, not a single person came to buy. (Was it Divine intervention or staunch community support?) Due to the uncertainty of the situation, Fr. Lussier also tried to buy Drs. Struthers and Arthur's hospital, but to no avail.

In May 1897, Goodfellow's creditors seized the hospital and its contents. As a result, the lease of the previous year became null and void. Fr. Lussier lost the $800 rent he had paid as well as the $150 in medicine, cooking utensils, pieces of furniture, and the eight furnished beds he had bought. These (and the building itself) were all sold to pay the remainder of the mortgage. Still undeterred, Fr. Lussier signed a lease with the new proprietors.

Also in May 1897, the Superior General of the Grey Nuns of Ottawa, paid a visit to St. Joseph's Hospital. Endowed with a remarkable financial aptitude, she quickly assessed the economic situation faced by the hospital. She immediately got in touch with Bishop O'Connor of the Diocese of Peterborough (which Sudbury was then a part of) with an idea.

The bishop offered Fr. Lussier a piece of land that was the property of the Episcopal Corporation of the Diocese. Following this offer, a letter arrived from Ottawa informing Fr. Lussier that the Order of the Grey Nuns would undertake, at their own expense no less, the building of a $10,000 hospital on the ground offered by Bishop O'Connor (When the hospital was completed, it ended up at a cost of $25,000).

This news brought great relief to Fr. Lussier. At the time of its founding, he had undertaken to support the hospital in all of its vital needs, to provide the nuns with shelter and food, and to pay each one a yearly salary of $100. His only source of revenue was "tickets" which he sold to lumbermen and miners of the region. These tickets guaranteed the bearer free treatment at the hospital.

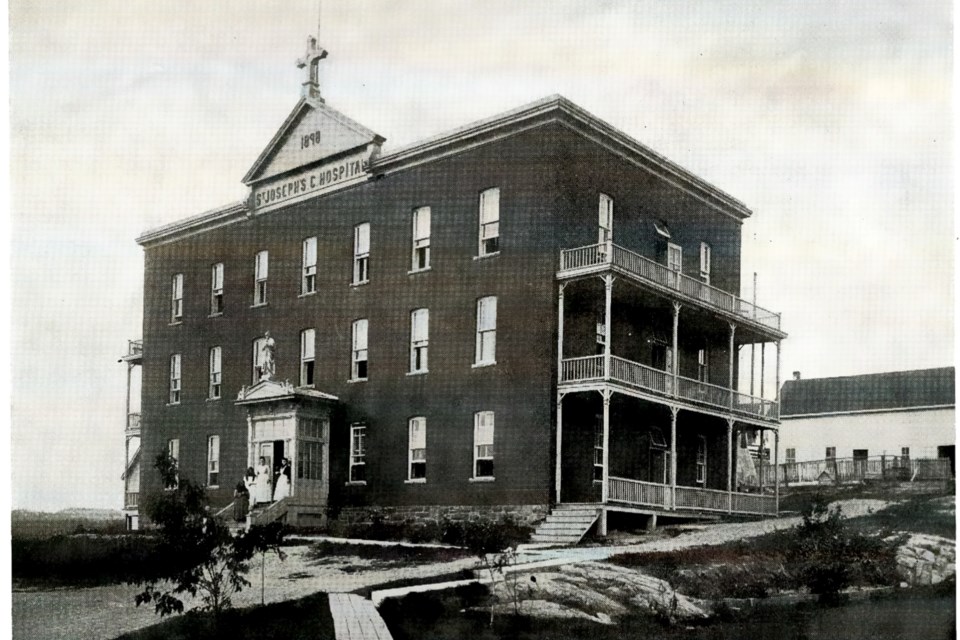

On May 17, 1898, construction began with work progressing so rapidly that by Dec. 1, the nuns entered their own St. Joseph's Hospital overlooking the city from “Mount St. Joseph.” They commenced with 11 patients, all transferred from the Dufferin Street location. The new building covered an area of 4,206 square feet.

After the Sisters occupied the hospital, they soon had a monthly average of 23 patients. In February 1901, an epidemic of smallpox, most likely brought in from one of the many nearby lumber camps, caused the temporary quarantining of St. Joseph’s Hospital. Later, in November of the same year, town council had electric lights installed on the hospital premises.

In April 1907, the Hospital’s first enlargement began with the cornerstone being blessed by Bishop D.J. Scollard. Less than a year later, in March 1908, the first patients were being treated in this new wing. With this expansion, the number of patients treated in a year passed 1,000 for the first time.

In January 1910, a railway accident on the Soo Line saw the majority of the 47 wounded being brought to St. Joseph’s for treatment. After having to deal with such a large and immediate influx of patients, as well as the past history (and potential future) of smallpox epidemics, the first “regular” Medical staff was organized, in November 1910. The staff consisted of Dr. Mulligan, Dr. Torrington, Dr. Hurtubise, and Dr. Patterson.

On Jan. 11, 1911, the School of Nursing officially opened and by November of 1913, the first nursing school graduation of three nurses took place. Eventually, it would furnish an average of 10 to 15 graduates each year.

Also in 1913, Doctors Cook and Arthur’s General Hospital on Elm Street was closed. The 20 patients remaining there were transferred to St. Joseph's, which had also just dedicated their new surgical department.

In September 1917, the very first X-Ray equipment was installed at the hospital. With advancements in technology and techniques, this equipment would be “renewed” twice in the hospital’s lifetime (in 1931 and 1943). The next month, the Governor General, the Duke of Devonshire, and his wife visited the hospital (probably there to check out the automatic electric refrigerator which was just installed on Oct. 24. 1917.

In October 1918, the Spanish Flu epidemic hit Sudbury and the resulting increase in patients (500 more than the previous yearly average) saw the hospital treat over 2,000 people per year over the next two years. All of the newer methods of treatment developed during the First World War were subsequently introduced to the community here. New anaesthetic procedures, intravenous therapy, antiseptics and sterilization replaced the old "Horse and Buggy" stage of medicine.

By June 1921, the hospital’s use by the community had far outstripped its current size and construction of a new wing initially to be used for chapel and nurses’ rooms was commenced. In December 1922, hospital administration opened the office of records and medical laboratories. With that, hospital efficiency continued to keep pace with medical and surgical progress and led to St. Joseph’s receiving the A1 classification from the American College of Surgeons in January 1923.

The Grey Nuns continued to improve St. Joseph’s for the good of their patients (both current and future). The year 1927 witnessed the construction of a fireproof laundry (April) followed by the opening of the maternity ward (August) in the wing originally built in 1907. This was followed, in 1928, by the construction of a central heating plant and 113-foot tunnel to join it to the main building.

In 1929, on the eve of the Great Depression, it was decided that the hospital was still too small for the growing population of the soon-to-be City of Sudbury (incorporated in 1930), so in April, a fireproof wing was begun at the west end of the hospital. On Christmas Eve 1930, the Maternity Ward was transferred into this new wing.

In 1937, INCO made the first of many donations to the hospital when it gave $5,000 to the Grey Nuns, with the stipulation that $3,000 would go towards the building debt and $2,000 towards “scientific progress” of the facility. That year also saw the hospital staff (now numbering above 50) treat over 5000 patients for the first time.

In the lead up to the hospital’s 50th Anniversary in 1946, four more important advances were made for the benefit of the patients and the community at large: the first portable X-ray apparatus was introduced (1938), an electric ironer was purchased for the laundry at a cost of $18,000 (1943), the hospital became the first Canadian hospital to install 25 modern individual cubicles in their nursery (1944), and the same month as the end of the Second World War (April 1945) saw organization of a clinic for cancer.

At this point, St. Joseph’s Hospital had reached its apex and, unfortunately, a slow decline (though not noticed by the public) would begin from this point onwards. It began, in 1950, with the opening of the Sudbury General Hospital of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. This was followed by the opening of Sudbury Memorial Hospital in January 1956.

These three hospitals would work together in the community on different projects, for instance, Meals on Wheels, which began in Sudbury in 1971. Meals were cooked at St. Joseph's Hospital and were delivered by the Red Cross three times a week to six recipients. St. Joseph's, Sudbury General, and Memorial Hospital later alternated every three months preparing the meals until 1974 when the operation was moved to Pioneer Manor.

Unfortunately, the first soundings of the death knell for St. Joseph’s were rung in 1965 when plans were commenced for what became the Laurentian Hospital. The building’s construction was expected to start in November 1970 with a view to an opening in 1972 (later becoming 1975). As published in Le Voyageur in 1969, with the future opening of Laurentian, plans were beginning to be made to tear down or repurpose St. Joseph’s Hospital after just over 70 years.

In July 1974, the St. Joseph's Hospital Board of Governors decided to permanently close the hospital's emergency department. The Sudbury Regional Health and Social Services Committee requested the hospital reconsider the decision until the remainder of the hospital was closed upon the opening of the new Laurentian Hospital. As Councillor Ricardo de La Riva said at the time, “I don't think there's anything wrong with keeping these services going for another 18 months or so. It's been open for 80 years already (78 years, in reality)..."

On June 28, 1975, after 79 years of service to the community, St. Joseph’s Hospital closed its doors for the final time. As reported in “Le Voyageur” four days later, “At its last meeting, the Regional Council voted unanimously to make a gesture that would underline the gratitude of this region for the 79 years of service given to the community by the Sisters of Charity. A historical plaque affixed to the walls of St. Joseph's Hospital will remind us that from 1896 to 1975 the nuns generously responded to the needs of the population.”

In July 1978, the Northern Life announced that a feasibility study was in the process of being carried out on the then 80-year-old building to determine whether it could become the cultural centre for Sudbury's Francophone community. The property, which was owned by the Diocese of Sault Ste. Marie ceased operating as a hospital in 1975 and remained vacant ever since.

Concurrently, steps were being taken to formally transfer ownership of the old hospital, which was being gifted by the church, to Le Centres des Jeunes. When construction finally began, the renovations to create what was to be named “Place St. Joseph” included the demolition of two old wings and the removal of walls to enlarge the cubicle-like rooms.

Even though it no longer exists, what remains of St. Joseph's Hospital will continue on as a monument to the Grey Nuns of the Cross, to its dedicated Medical Staff and to Sudbury’s history.

Well dear readers, thank you for being patient with me while we took another trip into the past. Now it’s your turn to share with us the memories that you have been nursing all these years. Were you (or a loved one) a patient at one time? What was your experience? Or maybe you worked there? Share your memories and photos by emailing Jason Marcon at [email protected] or the editor at [email protected]

Jason Marcon is a writer and history enthusiast in Greater Sudbury. He runs the Coniston Historical Group and the Sudbury Then and Now Facebook page. Memory Lane is made possible by our Community Leaders Program.