Even with approximately 250,000 lakes and over 100,000 kilometres of rivers (yes, 1/6th of the surface of this massive province of ours), all of that potential hydro power at its fingertips couldn’t help Ontario, and consequently Greater Sudbury, to escape the electrical disaster that headed our way in the afternoon of August 14, 2003.

If you’re reading this on August 16, it has been exactly 20 years since the complete effect of the largest North American blackout was reversed and all of Ontario was returned to a state of semi-normalcy.

So, what exactly happened on that hot and humid mid-August day?

According to an organization known as the New York Independent System Operator, which is

responsible for managing the power grid for that US state – a 3,500 megawatt power surge directed towards Ontario affected the electrical transmission grid at 4:10 p.m. (to put that number into perspective, ONE megawatt of power can light up approximately 1000 homes at once).

Over the next 30 minutes, a catastrophic cascade of outages was reported in parts of the American States of Michigan, Ohio, New Jersey and New York, Vermont, and Connecticut, as well as in Southern Ontario, gradually creeping into the north.

When all was said and done, a rough triangular area of Northern Ontario from Sault Ste. Marie to James Bay to Ottawa joined the Southern portion of the province in darkness (Northwestern Ontario was not affected).

According to the official analysis of the blackout which was prepared by both the Canadian and

American governments, more than 508 generating units at 265 power plants shut down during the subsequent chain reaction of outages.

In the minutes prior to the event, the originating power system was carrying 28,700 MW of load (remember that description of a megawatt above?

That’s the equivalent of 28.7 million homes!). At the height of the outage, the load had dropped to 5,716 MW, a loss of power of 80 per cent.

The blackout’s initial cause was a software bug that was found in the alarm system of the control room of FirstEnergy, an Akron, Ohio–based company. This bug made power station operators unaware of the need to redistribute electrical load after overloaded transmission lines drooped into trees growing below power lines.

It was a hot day (over 31 C) in much of the Northeast region of the continent, and that heat played a role in the initial event that triggered the wider power outage. The high ambient temperature increased energy demand, as people across the region turned on their fans and air conditioning. This caused the power lines to sag as the higher currents passing through heated up the lines.

What should have been a manageable local blackout cascaded into the collapse of much of the

Northeast region’s electricity distribution system. The indicators in the main control centre for Ontario’s power grid showed that the province was short 8,000 megawatts of power. That’s about one-third of the required supply on a hot summer day. As Kim Warren, the manager of the main control centre said:

“This was the entire power system imploding, falling down. The wallboard we have was lit up like a Christmas tree.”

Essential services remained in operation in some of the affected areas. However, in others, even backup generation systems failed. Water systems in several cities lost pressure, forcing boil-water advisories to be put into effect. Telephone networks generally remained operational, but the increased demand triggered by the blackout left many circuits overloaded.

(Even now, though it’s mostly through text, we find ourselves always checking with others to see how localized our power outages are). The telephone companies requested that the public keep landline phone calls to a minimum, and the authorities asked that residents call 911 only in a true emergency.

The more rudimentary cellular service of the day was interrupted as mobile networks were overloaded with the increase in volume of calls. And even so, many cell sites were out of commission due to the power outages. Television and radio stations remained on the air, with the help of backup generators, although some stations were knocked off the air for periods ranging from several hours to the length of the entire blackout. (Of course, who in the blacked-out service area did they expect to be watching, we don’t know)

Traffic lights, which had no backup power, were all knocked out. This created a situation where all intersections were to be considered an all-way stop. Of course, coupled with the beginning of evening rush hour, this had the potential to be a disaster.

In many major and minor intersections in large cities, such as Ottawa and Toronto, ordinary citizens took it upon themselves to begin directing traffic until police or others relieved them. Since there were not enough police officers to direct traffic at every intersection during the evening rush hour, passing police officers distributed fluorescent jackets to civilians who were already directing traffic. It was reported at the time that drivers and pedestrians generally followed the instructions from them, even though they were not police officers.

While the actual cause remained shrouded in confusion, residents in many towns and cities across Canada's largest province, coped in good humor. Many people took advantage of the unusually dark night to stroll under the stars. Families emptied their refrigerators and barbecued in their yards. It was reported at the time that at the supermarkets, there were long lines of shoppers, with cashiers tallying sales with calculators. And, consumers deprived of the use of debit and credit cards, were found in some cases to be signing I.O.U.'s.

In areas where power remained off after nightfall, the Milky Way and orbiting artificial satellites became visible to the naked eye in metropolitan areas where they ordinarily could not be seen due to the effects of light pollution. All airports within the affected area had been closed immediately, so there were no take-offs, and incoming flights had to be diverted to airports with power. The night sky was a rarely seen canopy of dazzling stars, twinkling down on darkened cities through soft summer heat that lingered into the evening.

Toronto Mayor Mel Lastman was quoted at the time: “Everything is going smoothly. The public has been outstanding. They are not losing their tempers, and they are even directing traffic.''

The office of Prime minister Jean Chrétien, initially announced that the blackout was caused by lightning in northern New York State but was later forced to retract that statement. The nation's Defense Minister, John MacCallum, said later that the blackout originated at a nuclear power plant in Pennsylvania, according to a report on the CBC. Unfortunately, he did not explain his remarks and they were later retracted as well.

People rushed to battery-operated radios to get any news that they could find, and found that there was scant information available. When the power went out, people assumed that the hot and muggy weather, similar to the conditions that had caused rolling blackouts the previous summer was the culprit. But as the blackout dragged on, most people came to the realization that the problem was much more serious. Rumours at the time included a fire in New York City, terrorism and even computer viruses.

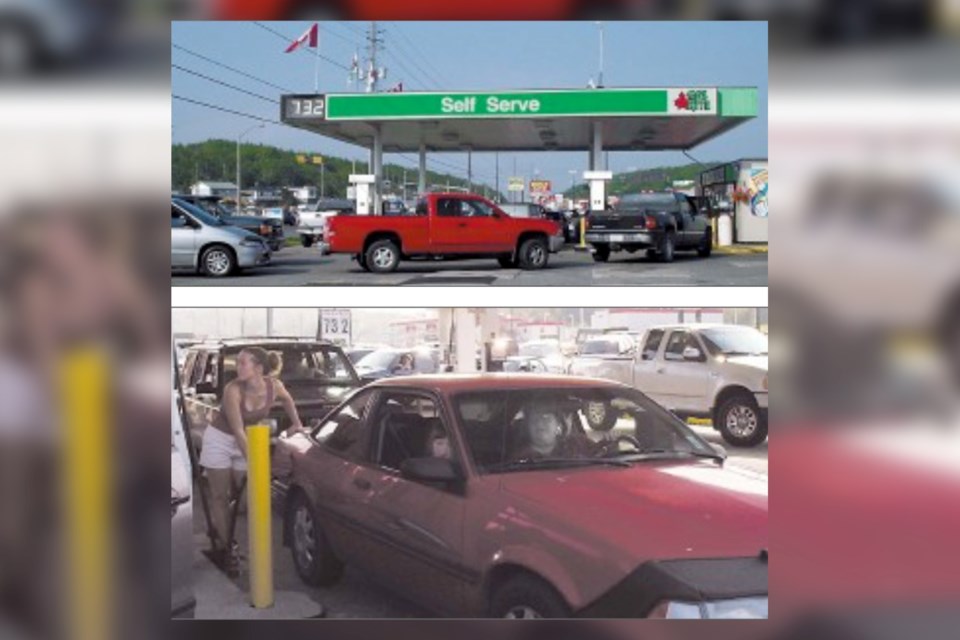

Large disruptions of truck traffic across northeastern Ontario, including a major backlog near North Bay, were reported at the time due to the unavailability of fuel (gas stations require electricity, in this case from gas generators, to pump the fuel…oh the irony!).

On the evening of August 14, Ontario premier Ernie Eves declared a state of emergency, instructing nonessential personnel not to go in to work the next day and that rolling blackouts could occur for the coming weeks. Residents were asked not to use televisions, washing machines, and especially air conditioners if possible, and warned that some restored power might still go off again. And, even though the full state of emergency was lifted the very next day, Ontario residents were still warned that the normal amount of power would not be available for days, and were still asked to reduce power consumption.

Most of the major municipalities of Southern Ontario had their power restored by midnight (within seven hours of the onset). Half of the affected portions of Ontario regained power by the next morning. By early evening of August 15, only two airports, Cleveland Hopkins International Airport and Toronto Pearson International Airport, were back in service. Full power was only restored in the province on August 16.

At the time, it was the world's second most widespread blackout in history, after the 1999 Southern Brazil blackout.

The outage, which was much more widespread than the Northeast blackout of 1965 (when over 30 million people and 207,000 square kilometres were left without electricity for up to 13 hours) affected an estimated 55 million people, including 10 million people in Ontario and 45 million people in eight U.S. states.

For the first two days of the recovery period, diversion of water from the Niagara River for hydroelectric generation was increased to the maximum possible level, normally drawn at night and during the winter in order to maintain the scenic appearance of Niagara Falls.

The resultant drop in the river level below the falls meant that the Maid of the Mist tour boats had their operations suspended temporarily.

The reliability of the electrical grid was called into question and required substantial investment to repair its shortcomings. The extra publicity given to Ontario's need to import electricity from the United States, mostly because of a decision by the government not to expand the province's power generating capabilities, may have adversely affected the Conservative government. In the provincial election held in October 2003, the Conservative government of Premier Ernie Eves fell.

His handling of the crisis had also been criticized since he was not heard from until long after Prime Minister Chrétien and both New York Mayor Bloomberg and Governor Pataki had spoken out.

What’s the number one fear (or at least near the top of the list) for all miners? I’m sure they would say that being trapped underground would be it. Unfortunately, about 170 miners were marooned underground in four Falconbridge mines across the Sudbury area when the power went out. The first few minutes after the blackout did cause concern for company officials, but they stated that the workers were safe and could be evacuated if necessary, but were not, due to the inherent risks of doing so with no power. A committee of Falconbridge officials met with officials from Ontario Hydro, Hydro One and the Ministry of Labour to devise a scheme that would get power to each different mine as quickly as possible, said Company spokesperson Martin Parnell, at the time.

Thirty workers stuck at Lockerby Mine were the first group to be brought up, at 12:45 a.m. on August 15 (nearly nine hours after the blackout hit). Followed by 68 people who were brought up from the second mine at 2:45 a.m., another 13 from a third mine at 3:15am and the final group of 37 from the fourth mine at 5:40 a.m. It took a total of 12.5 hours from the second the lights went out until the last of the workers was safely evacuated.

In late August 2003, just two weeks after the blackout, Greater Sudbury manager of corporate services Doug Wuksinic spoke of the Aug. 14 blackout compensation package that was announced by Premier Ernie Eves which meant several hundreds of thousands of dollars for the city.

All of the costs deemed necessary for compensation included: overtime wages for public works, police, fire and ambulance services; additional purchases of everything from gas and diesel fuel for emergency generators to water bottles for the workers trapped underground at Falconbridge; lost revenues as a result of things such as the free transit offered; and wages paid to city workers asked to stay home to conserve energy.

Even after 14 days, some city services and venues were still not back to normal hours. The ice was lost at the arena in Azilda and had to be rebuilt and all arenas were only expecting to resume normal operations the following week (three whole weeks after the blackout). Powering the city’s 13 arenas had an equivalent power usage as air conditioning 500 homes.

As August wound down and prepared to give way to September, Greater Sudbury was second only to Ottawa in energy conservation for the week following the blackout (Out of 10 Ontario cities monitored for energy conservation) Sudbury was able to reduce its power consumption as a whole by over 20 per cent. In a press release, Greater Sudbury Utilities Chair Paul Marleau stated: “Our citizens’ true community spirit glowed throughout the crisis…”

Mayor Jim Gordon said at the time that whenever there is a crisis, the people of Sudbury rally. He continued by saying: “I really believe it’s the way we are in Sudbury and I think the people here deserve a lot of credit for being so socially conscious.”

As John Jeza, vice-president of Greater Sudbury Utilities, professed in 2003, Sudbury’s performance was pretty phenomenal. Taking into consideration the soaring heat and humidity, he stated that Sudbury’s total energy demand would typically have been in the 125-130-megawatt range. However, due to the “phenomenal participation by Sudburians this past week,” the city’s energy consumption came in at a frugal 101 megawatts. Jeza said that he’d “seen examples of it (energy conservation) everywhere. The colleges and university... the city had their air conditioning turned down, computers off, lights off...even little corner stores, people were telling me, had turned off whatever lights they could.”

Even while out for an evening walk in the weeks post-blackout, Jeza said that he passed by over 200 homes in his neighbourhood and was heartened by what he saw. “It was unbelievable!” he said. ”Over 90 percent of the homes only had one light on...no exterior lights...and I couldn’t hear any air conditioners.”

The administrators of both Extendicare locations in Sudbury wrote in to the Northern Life after the blackout to “thank those who assisted in ensuring the safety and well-being of residents during the power outage.” They continued to say that they “are proud to say resident care and safety were maintained as a direct result of the generosity and determination of our residents, their families, staff, volunteers, neighbours, the local fire department, and our business partners. Many of our “helpers” arrived ready to lend a hand before any requests for assistance went out. Those already on duty kindly stayed until late in the evening and returned again first thing the next morning.” These acts of generosity and determination demonstrated what community is all about.

In the aftermath of the blackout, Mayor Jim Gordon requested that citizens to pull together to help those in need. “Those in need who lost a fridge full of groceries and had to throw away food from their freezers …This is especially true for our seniors and others on fixed incomes,” said Gordon. He urged “everyone who can to donate non-perishable food items to local food banks (and that) those in need should contact their local food bank for assistance.” Gordon commended Sudburians for their giving spirit during times of crisis.

Canadian Blood Services took out an ad post blackout under the title, “You continued to shine throughout the blackout.” Due to the blackout and its immediate aftermath numerous blood donor clinics in Ontario had to be shut down which caused a potential shortage of blood in Canada.

Fortunately, people from across the country quickly responded by giving blood, and helped to replenish the supply which ensured that hospitals and patients continued to receive the blood they needed. As the advertisement concluded: “Once again, you showed that when there’s a need, Canadians are ready to roll up their sleeves and help.”

Now, dear readers, it’s time for you to roll up your sleeves and help us out. After 20 years, let’s see if your Memories burn brightly of the night the lights went out (not in Georgia, luckily). Were you stuck in traffic, or perhaps directing that traffic? Did you get a chance to enjoy the rich blackness of the vast night sky with absolutely no light to pollute your view? Or, were you too busy as one of the front line workers helping to keep everything running smoothly in health care or infrastructure? And, of course, do you have any photos of the night-life after the city was plunged into darkness or any of the chaotic aftermath.

Share your memories of the 2003 Blackout by emailing the author at [email protected] or [email protected].

Jason Marcon is a writer and history enthusiast in Greater Sudbury. He runs the Coniston Historical Group and the Sudbury Then and Now Facebook page. Memory Lane is made possible by our Community Leaders Program.