How much money am I going to get, and when?

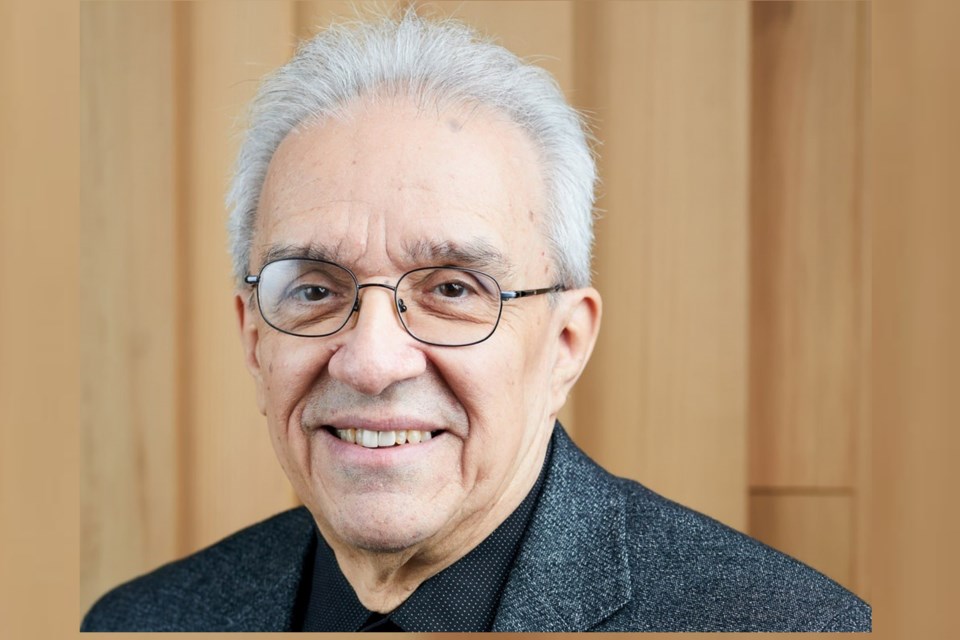

That’s the burning question in Robinson Huron Treaty Territory states a recent release form the Robinson Huron Treaty Litigation Team, written by the Office of the Mizhinawe. And while there is a great deal of solicitor client privilege involved, Sudbury.com spoke to Justice Harry LaForme, the Mizhinawe, to find out what the answer might be.

In this case, the answer is complex, said LaForme.

On June 17, the federal and provincial governments announced they reached a proposed $10 billion settlement with the Robinson Huron Treaty Litigation Fund (RHTLF), representing the 21 Robinson Huron First Nations. The proposed settlement includes $5 billion from Canada and $5 billion from Ontario to be paid to all 21 First Nations included in the treaty.

The settlement is in relation to the Robinson-Huron Treaty of 1850 Annuities Statement of Claim, which was launched by the RHTLF in 2014, involving a claim for resource revenues. At the time, the settlers of the area were driving economic growth on land that did not belong to them, encroaching on traditional lands. A treaty was signed in 1850.

Under the treaty, the Crown promised to pay a perpetual annuity of £600 ($2,400), which in 1850 worked out to approximately $1.60 per person. But the Crown provided an additional incentive for the Anishnawbek communities to sign the treaty.

Called an ‘augmentation clause', it meant if further wealth was generated in the territory, the Crown was obligated to increase the annuity.

But the annuity was not increased until 1874, despite the economic growth on the land and then, it was only $4 per person. The $10 billion settlement is to compensate for the years the amount was never raised. It could be raised for future payments, but that is a separate issue under the claim and will be handled later.

Once the settlement has been signed, and the Superior Court has issued its judgment endorsing the settlement, the RHTLF will move ahead with the next steps in the process, as prior to the negotiations beginning, there was a compensation disbursement agreement adopted by First Nations chiefs and councils. The First Nation councils will be responsible for allocating funds for both community purposes and per capita payments to individuals.

It is now up to the Mizhinawe, LaForme, to consult with all the nations, to hear their concerns and needs, and then to prepare a report for the chiefs of all 21 First Nations, including Atikameksheng Anishinawbek’s Gimaa Craig Nootchtai and Wahnapitae First Nation Chief Larry Roque.

Laforme is Anishinaabe from the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation. He served on the Ontario Court of Justice (General Division) and was the first Indigenous appellate judge in Canada.

The Mizhinawe, a role that Laforme was appointed to in April, is a traditional role that was in place in 1850 when the treaty was signed. Though it is still being researched by First Nation historians, the meaning, said LaForme, is akin to “Near Chief.”

“My job, my mission really, is the same as it was in 1850: to provide a vehicle for one chief to communicate with another chief,” said Laforme. “I would be the message carrier, I would say what the chiefs are talking about and deliver that to other chiefs. I would give advice to the other chiefs, when asked.”

The Mizhinawe, in collaboration with the Robinson Huron Treaty leadership, will engage in consultation sessions about the annuities settlements.

“What we are doing is giving the members a chance to tell us, in their own words, how they think that distribution of settlement monies should go, and they're given the opportunity to get as much information as we can give them,” said LaForme. “And then we asked them how to balance any community needs versus the individual needs of the First Nations memberships.

LaForme is also discussing the compensation disbursement agreement with these groups, but the details of that agreement are privileged under law.

In general, LaForme said the sessions have been “wonderful.”

He said while some feel the money should be given out to each individual, as the $4 annuity cheque currently is, others are looking for community funding and in particular, funding for youth.

“My job as Mizhinawe is to take all that information and see if I can make any recommendations about how the disbursement should be done,” said LaForme, but noted that they are just recommendations. And those will be just recommendations. “But they're important. It's a way to communicate with all Robinson Huron members who take the time to come to these meetings.”

He said the meetings have been well attended so far and LaForme hopes to complete his work within six to eight months, including providing a report with recommendations.

According to a treaty litigation fund engagement document, it’s hoped that the recommendations will not only find a balance between collective community needs and individual needs, but also developing a process for addressing the one per cent of compensation that has been set aside for beneficiaries that are not members of the 21 Robinson Huron Anishinaabe First Nations, developing an alternative dispute resolution process to deal with any concerns from individual annuitants regarding the compensation disbursement agreement (and the one per cent distributions), and the use of the 10 per cent of compensation set aside in the agreement for collective purposes.

“Some of the issues are really complex, as you can imagine, like membership, who's entitled and who's considered a beneficiary under the treaty,” said LaForme. “Because of colonization and the rules that were provided by various governments of Canada, those are things that have to be worked through, and worked out, because there's many, many permutations that can happen.”

For example, said LaForme, many Indigenous women were “enfranchised” if they married a non-Indigenous man, in that they would have to give up their status, according to the Indian Act. “We're not going to be relying on that, we're going to be relying on the traditions of Indigenous governments and we're going to develop our membership that way.”

The same release that asks the burning question of how much and when, also describes the treaty-making process as a way “to expand and strengthen kinship, keeping us together and alive in a radically transforming world.”

“As this new history begins to unfold, it’s important to remember the principle of mutual care that was revered by our ancestors when they entered into the treaty-making process,” it continues. “They wanted us to prosper as individuals, but they also wanted to ensure we worked together – not just for us in the present, but for future generations.”

For more information on the consultation process, visit www.robinsonhurontreaty1850.co