SAGUENAY, Que. — A forensic biologist told a jury on Tuesday how a DNA research tool helped police hone in on an alleged killer who is now charged with the sexual assault and murder of a 19-year-old junior college student nearly 24 years ago.

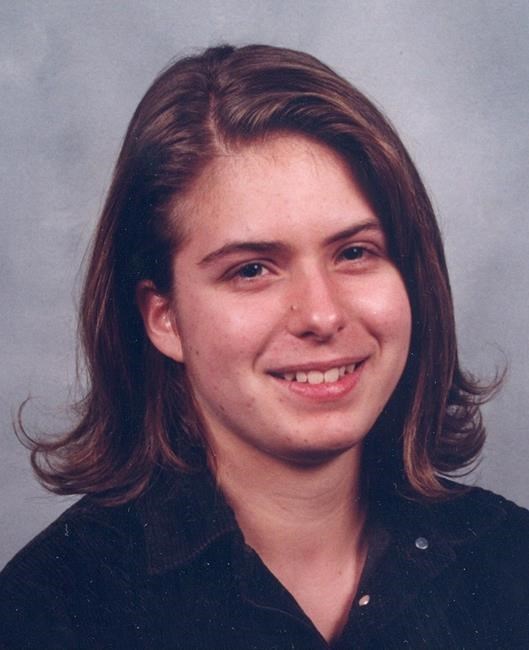

Valérie Clermont-Beaudoin testified at the Saguenay, Que., trial of Marc-André Grenon, who has pleaded not guilty to the first-degree murder and aggravated sexual assault of Guylaine Potvin in April 2000.

Clermont-Beaudoin said the unidentified male DNA collected at the crime scene was run through a database in 2022 as part of "projet patronyme," which analyzes the Y chromosomes of DNA samples and suggests surnames that could be associated with them.

She explained that Y chromosomes are passed down from father to son, as are last names in most cases, which allows biologists to identify tentative last-name matches for unknown DNA.

"The Y chromosome will be transmitted from father to son, from generation to generation indefinitely, until there is a break in the line," she said. She said such a break happens when a son no longer shares his father's DNA, as is the case in an adoption, sperm donation, or an extramarital affair.

Clermont-Beaudoin said the database is run by Quebec's forensics lab, and includes some 138,000 profiles gathered from members of the public who upload their DNA to various websites and consent to the information being made public.

She said the male DNA from a sample collected under Potvin's fingernails was entered into the database in 2022. She said the software emits a list of potential last names that could be associated with the DNA, which are ranked by level of interest based on the degree to which they match.

In this case, she said the name "Grenon" came out at the top of the list, scoring 94 out of a possible 98 points. She said the information was given to police officers, who used it to focus their investigation.

Clermont-Beaudoin's testimony is key to understanding how police managed to identify Grenon as a suspect more than 20 years after Potvin was found strangled and sexually assaulted in her basement apartment in Jonquière, now a part of Saguenay, some 215 kilometres north of Quebec City.

The trial has previously heard that Grenon's name had surfaced in the investigation because he once lived in an apartment near to the one where the victim was found dead.

The jury also heard that, following the results of the forensic lab's research, officers tracked Grenon to a movie theatre and gathered a new DNA sample from a discarded drinking cup and straws he had used.

That sample was found to match the DNA from the crime scene, and the match was confirmed with a second DNA test taken after Grenon's arrest, the Crown has alleged.

Clermont-Beaudoin said the surname search is used only in cases "when there are no other investigative paths available," and no main suspects.

She said the search provides only a last name — not a suspect — to help police narrow down their investigation. She said it is up to police to link the suspect to the crime by obtaining a new DNA sample to compare to the one left at the scene.

Justice François Huot, who is presiding over the trial, told the jury that the DNA database results should be understood as a tool that helped guide the investigation but that could not be used to establish the suspect's guilt.

"You cannot use the fact that Grenon is considered a surname of popular interest to draw any references whatsoever as to the guilt of the accused," he said.

Under cross-investigation by the defence, Clermont-Beaudoin acknowledged that the database used to search last names is not regulated by any law in Quebec, and that the data it contains is extracted from outside websites, without a process to verify it.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Jan. 30, 2024.

— By Morgan Lowrie in Montreal

The Canadian Press