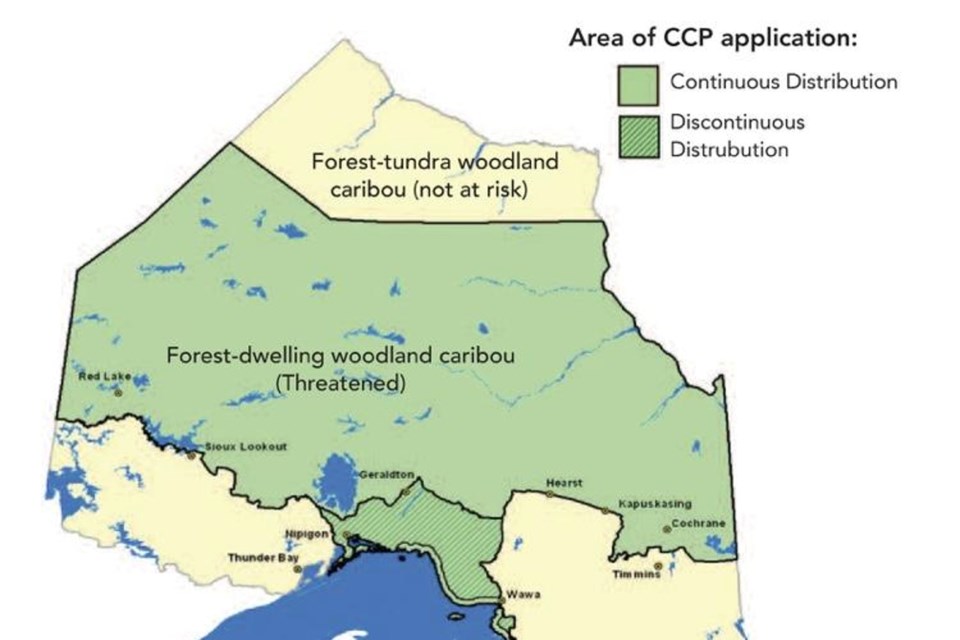

It was recently announced the provincial government is going to spend $29 million of your dollars over the next five years to protect and conserve Ontario’s “boreal” caribou population (1), presumably as described in the Woodland Caribou Conservation Plan (CCP, 2).

I have written a great deal about the mismanagement of moose in Ontario and the conflict between moose and caribou policies (3 and 4). The best thing going for moose has been that MNRF have ignored caribou and their own policies. Now that there is money and political initiative, that may no longer be the case.

This investment certainly has me confused for a number of reasons. I was a public servant for 27 years, and by definition, am on the lower end of the intelligence scale, so my confusion is understandable.

It should be noted that caribou are managed by the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation, and Parks, while moose and habitat are managed by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. That’s a good place to begin confusion.

As is noted in the CCP, woodland caribou are “ecologically important and have intrinsic (“essential”) value. They are indicators of the health of the boreal ecosystem.” That said, they have no conventional economic value and almost nobody in Ontario will ever see one. I am not a “money means everything” kind of person and I do accept that caribou must be preserved, but at what cost, and more importantly, on the basis of what evidence?

Please bear with me and I’ll explain.

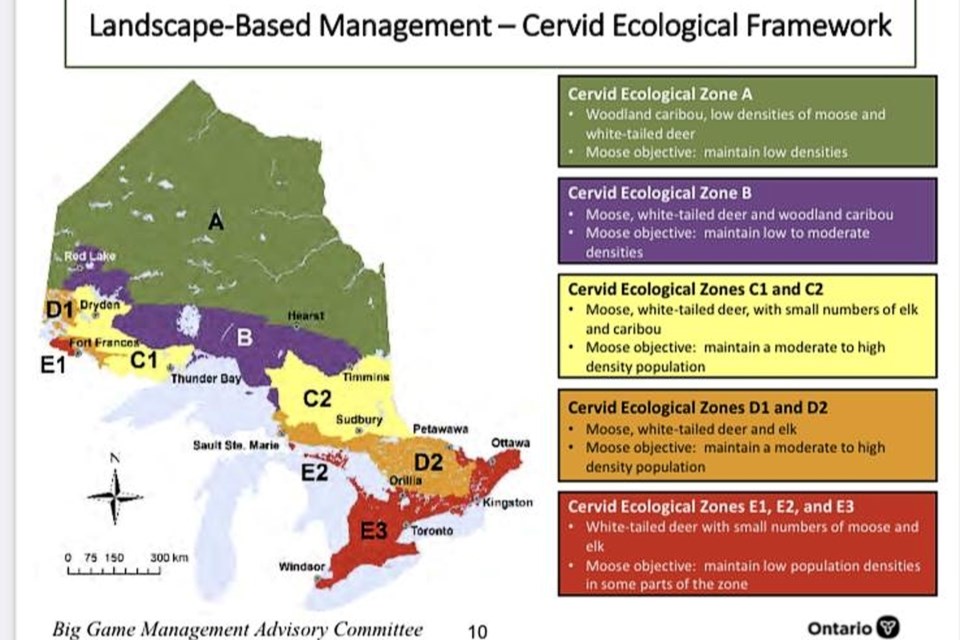

I use economic value only in relation to the conflict with moose and only in Cervid Ecological Zone (CEZ) B (5), where my information tells me there are very few caribou. In this area, moose do have huge economic, food and social values for First Nations, residents, and the tourist industry. Like caribou, moose are also indicators of the health of the forests and have intrinsic value.

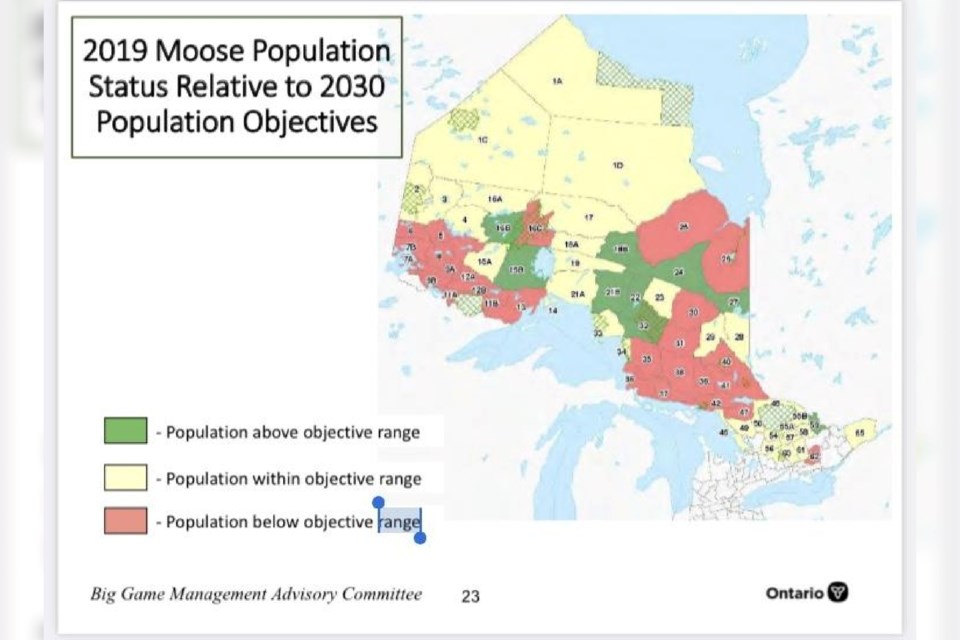

The most obvious conclusion since moose populations are declining, is that moose ecosystems are not healthy, yet MNRF is doing nothing effective to remedy that?

Although the caption for CEZ B does not identify an objective for caribou, it is to “minimize impacts and maintain/restore populations.”

There are a number of statements in the CCP that bear noting and comment in relation to the announced investment.

1: Under “the cautionary principle … incomplete information should not be used as a reason for delaying conservation action” (p 2). My confusion with this statement is that the CCP was originally written about 2008 when Donna Canfield was minister, but the plan was not approved until 2020, then immediately revised in 2021. Why the 12-year delay in taking action – a clear contradiction to this statement? It further appears the absence of an approved policy was the justification for doing nothing to protect the Lake Superior population. More meaningless words sponsored by our government.

While there may be poor information regarding caribou in general, there is reasonably good information on them in CEZ B, and ample and excellent information for moose. My knowledge is that there are very few caribou in the vast majority of this zone. There is a small band in the northern part of Unit 4; a population that summers on the islands in Lake Nipigon and winters near Armstrong; remnants along the north shore and islands of Lake Superior (3 and 4), and; a population in the Nagagami Lake area, northwest of Hornpayne (this population is not included in caribou range and may no longer exist). A population that existed north of Dryden was extirpated in the late 1970s due to logging. I’d estimate that there are fewer than 200 – 300 caribou in this zone.

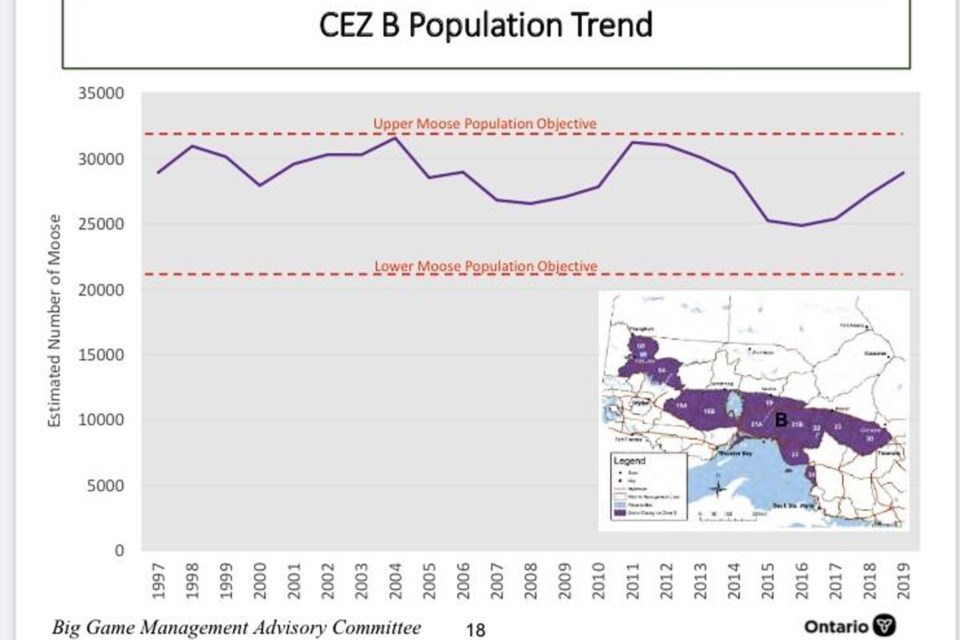

In contrast, there should be between 21,000 (19/100 sq km) and 32,000 (28/100 sq km) moose. (6). A recent computer-generated estimate was about 26,000. In order to prevent wolves from extirpating caribou, moose will have to be reduced to less than 11,000 (see point 3). The real potential for moose in this area might be something in the order of 65,000 (60/100 sq km), if determined through real adaptive management rather than a computer model.

Is protecting several hundred caribou in this zone (maybe even several thousand if the program is successful) worth the loss to the ecosystem of some 50,000 moose and the social and economic opportunities they could provide?

2: There is a commitment to use Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge (p 3), yet MNRF appears to have ignored the concerns of First Nations regarding the impact of the CCP on moose as they relate to traditional existence in CEZ B (5). Perhaps some of that $29 million is to provide farm meat to replace the loss of moose?

3: The goal of the CCP is to “improve connections among isolated mainland local populations, and … will apply to areas of continuous and discontinuous distribution shown in Figure 1.” “The Lake Superior coastal population will be managed for population security … and connectivity to caribou populations to the north.” (p 20). This means managing the area of discontinuous distribution to become suitable for caribou, and that means largely eliminating moose. It mentions the possibility of translocating caribou and describes the success of moving animals to islands in Lake Superior (p 20).

There are a couple of additional comments on the Lake Superior population. Since the plan was originally written, the government has done little to assist, and apparently inhibited translocations to restore the population in that area, especially after the severe winter of 2014. Again, policy words and actions are not consistent. Aside from the evidence that the government almost intentionally planned the extirpation of this population (4), recent surveys offer no evidence that this population still exists.

As a consequence, the “continuous distribution” along the lakeshore is erroneous. Except for the island populations, caribou have effectively been “discontinued’ in that area. There are no caribou left to “distribute” or to “connect” to northern populations. The plan needs revision before further action is taken as regards that objective.

4: The CCP states that “Ontario is committed to Aboriginal participation and Involvement …” (p 4). “This plan we will be initiating a number of recovery actions that will involve Aboriginal peoples, the scientific community, resource industries, other stakeholders, the general public and ministry staff.” (p 1). To the best of my knowledge, there has been no public involvement, First Nations object to the plan (7) and conservation groups, including the David Suzuki Foundation and the Wildlands League, describe the Federal-Provincial agreement as a “spectacular failure” (8).

5: Page eight states that “caribou have adapted to the fire-driven landscape.” The evidence that they require large areas of mature conifer forest, suggests that they have “survived” in spite of fire, not adapted to it. In contrast, moose are adapted to fires because most of their foods are early successional species that grow after fire. Any disturbance to the landscape will encourage moose, and that is bad for caribou. There are only two solutions to caribou management in the boreal forest: Either prevent habitat disturbance – both fire and logging — or to actively reduce moose numbers. Even that may be a problem because few hunters will hunt at those low densities.

6: It mentions that “caribou are very vulnerable to predators” (p 6), mainly wolves and black bears. Every paper I’ve read on caribou recommends that successful restoration (mainly in the face of human activity) will require predator control – killing wolves. Ontario’s plan is to manage predation through habitat management and “assessing the relationship between moose and caribou …” That relationship is already well-known. Caribou cannot survive at moose densities greater than 10/100 km sq. I eagerly await the plan to manage wolf populations through habitat, when they range in almost all habitat types across North America.

7: There are many references to uncertainties, and the main theme of the plan is to restore caribou through landscape-level habitat manipulation. One of the most interesting statements is that it will take 40 to 60 years after habitat disturbance before the effect of habitat “improvement” will be known. That’s a very large risk if the plan fails. There have been large fires in the past. How have they contributed to the population?

8: I had earlier reported that there was no evidence that Ontario was actually planning to reduce moose numbers to restore caribou. I checked a couple of units in response to specific requests. Folks have raised concerns about getting cow tags nearly every year in WMU 4, when there are so few tags elsewhere?

I looked at the harvest plan for that unit. The population was about 1,600 in 1982 and rose to 2,100 in 1994. It appears to have remained stable until 2014, when it was last surveyed. The total planned harvest remained relatively constant between 150 and 175, but the ratio has changed dramatically from 50-per-cent bulls, 20-per-cent cows, and 30-per-cent calves in 1983 to 35-per-cent bulls, 35-per-cent cows, and 30-per-cent calves after 2014. Total tag numbers have fluctuated somewhat going from 300 in 1983 to 400 in 1994, then 200 in 2014 and back to 250 in 2021. Tags have reversed from three bull tags for each cow tag to 1.3 cow tags for each bull tag. The actual harvest exceeded the plan in most years and averaged 250 until 2005. It has since declined to about 120 in the past few years.

Except for what I believe are poor planning criteria used recently (like wanting more bulls in the population than cows), I see no evidence to suggest the moose population is being reduced to protect caribou.

Ontario is embarking on a major and expensive experiment that will cost $5 million a year. I’ve never seen that much money in any wildlife project in Ontario, ever.

I’d really love to see a detailed budget for how that money will be spent. I don’t really have a problem with the spending — if it were based on good science and done in an effective manner. I’m not a caribou specialist, but I have doubts about how well that will be done.

MNRF has not been able to manage a species as simple as moose. Do they really believe that they have the skills to manage something as complex as caribou over a 40- to 60-year planning cycle, while ignoring some fundamental problems like active predator control, the impact of habitat disturbance, and the government’s initiative to develop the Ring of Fire (9), which includes all season roads?

I guess I’m confused as to why Ontario is prepared to spend $29 million on one species without any public consultation (it was posted on the Environmental Bill of Rights site for a month in 2022), yet are not prepared to implement inexpensive things like managing moose effectively, where public consultation was promised.

I’m confused why caribou populations, which are declining on the edge of the range where they interact with humans (and mainly because of habitat disruption that increases moose and predation) are so ecologically important, while moose populations, of equal ecological and much greater social and economic importance, will be allowed to decline well below historic levels? I‘m not alone at being confused. I think there is some pretty confused and seriously faulted logic on the part of MNRF.

On a related note, I sent a draft of the recent article regarding a moose harvest control plan to two members of the minister’s Big Game Management Advisory Committee. I suggested that they ask MNRF some questions, like exactly what are they doing that demonstrates “adaptive management” (as defined in a 2002 scientific publication regarding Ontario’s moose management, (10))?

I asked what MNRF was doing to reduce the moose in units where they are above the population objectives, and therefore deemed to be detrimental to the ecosystem? My suspicion is that the moose population is just fine, but the habitat-based computer population model is wrong. Just more meaningless words and a dependence on junk science.

Neither of the members of BGMAC has even acknowledged that correspondence, let alone answered my questions.

I sent a letter to the deputy minister with my concerns. Same result.

When you write the minister, who traditionally knows absolutely nothing about resource management, they just pass it on to their staff – the ones causing the problem. I really don’t think it is in their interest to tell him how badly they are failing, so they cover their ass with a response for his signature, as if he personally knows what he is talking about.

In an effort to get around this roadblock, I sent the most important articles to his constituency office, with a note that he should be apprised of the situation and not just pass it on as usual. I was informed that it was sent to his office in Toronto.

Again, I have heard nothing.

Now I can understand why MNRF, from the minister on down, may not like me, but it is generally considered a courteous business practice to at least acknowledge correspondence before ignoring it. The lack of reaction from all levels strongly suggests that MNRF is going to disregard their own information and continue to overharvest moose.

When governments are faced with a problem, they tend to apply the “four D’s”. They Deny that the problem exists (at least 20 years for overhunting); they Delay action (by having a review every few years and making meaningless changes that take time to assess); they Divide stakeholders (in this case by excluding First Nations and non-hunters from the decision process), and; then they attempt to Discredit those who raise the problem.

I suspected that’s where I fit in and why I have had no feedback from MNRF.

If I am not credible, that raises some questions. If they think my assessment of their information is incorrect, although the graphs speak for themselves, then perhaps they believe that the information I used was incorrect.

Of course, that raises the question of why I might have been provided incorrect information under a Freedom of Information request? You would think that if they gave me false information, they would at least be smart enough to give me stuff that demonstrates they are doing a fantastic job.

It is also interesting the acting director acknowledged my “knowledge and history of the program” and “my concerns and passion for moose”, but he wasn’t prepared to accept my advice.

From where I stand, that makes him either a liar or a fool, possibly both. You can bet he won’t write a letter like that ever again.

As Anna Baggio of the Wildlands League (8) said, the MNRF “talks and mines, talks and logs.” I would add “talks and over-harvests moose, talks and extirpates caribou.”

There is a totally unrelated message in this story and it has to do with democracy itself. When people fail to see their governments working on their behalf, being excessively politically correct and catering to minority demands to get votes, while ignoring clear evidence, they lose respect for those governments.

To paraphrase Arthur Finkelstein, a U.S.-based right-wing political consultant credited as the inventor of the political attack ad, “If a person believes the first thing you tell them, they will believe everything you say after that.”

This fact allows unscrupulous people to turn a kernel of truth into a field of lies for self-serving purposes. Dissatisfaction opens the door to misinformation and conspiracy theories. Most people won’t take the time to check for the truth and an amazing number of people won’t believe it when it is shown to them.

If our government does not start to respond to the interests of the majority of the population, especially in things that are evidence-based, and as simple as moose management, they threaten democracy itself.

Although moose mis-management affects a relatively small number of people, there are other issues that affect a majority. Health care is just one example. “Overreach of government”, fueled by misinformation, led to the Freedom Convoy with the intent of forcing the government to deviate from its efforts to prevent COVID-19 deaths. Many of the protesters would be dead or severely disabled (by polio as an example) without mandatory vaccines, which are offered based on the best science available.

Having lived a reasonably long life, I see this becoming far more prevalent than ever. The trajectory frightens me.

References

2: MNRF. 2020. Woodland caribou conservation plan. https://www.ontario.ca/page/woodland-caribou-conservation-plan

5: OMNR. 2009. Cervid Ecological Framework. https://www.ontario.ca/page/cervid-ecological-framework

6: BGMAC (Big Game Management Advisory Committee). 2019. Moose management review. https://www.ofah.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/MMR-engagement-presentation-May182019-compressed-002.pdf

7: First Nations criticize caribou protection plan - Sudbury News

9: https://www.ontario.ca/page/ontarios-ring-fire

10: BOTTAN, B., D. EULER, and R. REMPEL. 2002. Adaptive management of moose in Ontario. Alces 38, 1–10. https://alcesjournal.org/index.php/alces/article/view/495

Alan Bisset is a retired regional moose biologist and wildlife inventory program leader with the former Ministry of Natural Resources. He has written and published many papers on moose management, both Internally and in scientific journals. Bisset lives in Strathroy, west of London, Ontario. You can find his other submissions by typing “Alan Bisset” into the searchbar at Sudbury.com.

.jpg;w=960)