For those following Ontario’s moose management debacle, I thought I’d provide an update.

Clearly, MNR staff and the Big Game Management Advisory Committee (BGMAC) learned nothing from their own harvest and planning assessment failures that were published in October, 2022. The harvest control strategy remains unchanged for 2023 with over 16,000 tags available and a greater harvest of cows than calves.

In early March, I expressed my concerns to Mr. Graydon Smith, current minister of Natural Resources. When I did not receive acknowledgement of my letter and inquired if the minister had received it, I was informed that it was taking time (for the minister?) to review it.

In fact, as is usually the case, my letter was sent to, and answered by, the same people leading the mismanagement effort. It was a classic government response using hackneyed rhetoric but not actually addressing the issues.

The minister’s reply was delivered to me on April 27. It doesn’t surprise me that it took six weeks for MNR staff to try to figure out what they were doing in order to provide the minister with answers – and it was still meaningless?

The essence of the minister’s response was: A) That it was a relatively new program and would take time to assess; B) That MNR staff were working with the BGMAC, and; C) That they were seeing evidence of success.

No actual proof was offered.

As something of a sidebar, in spite of several requests, MNR have still not provided me with published information to support their strategy, or exactly how population objectives were determined and how they relate to the capability of the land to support moose. To get this information I filed another FOI request.

I was informed that the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA) provides for access to documents, but not “explanations” of why things are done.

I suspect the minister, Mr. Smith, knows almost nothing about resource management, let alone management, so on April 29 I wrote a letter refuting “his” explanation for doing nothing. I pointed out that the members of BGMAC were hunters and tourist outfitters who, under normal circumstances, should be excluded from objective harvest management planning because of their conflict of interest. That the 2019 report, written under their name, did not even include hunting as a possible cause of the decline in the moose population, shows just how biased they are. Blame everything except hunting in spite of solid evidence to the contrary.

I reminded him that half of the recent changes were “administrative” in nature, dealing with the way tags are distributed. That did not require assessment and if it did, had nothing to do with the excessive killing of moose that is causing the decline.

While the fundamental principle of the point system is sound and apparently well received by hunters, the actual tag allocation mechanism leaves a very large percentage of tags unallocated. Good for moose. Not good for hunters – if tags were actually planned to regulate the harvest effectively and to restore the population. Nearly 10,000 of 16,000 tags currently remain for the “second chance allocation“.

I would bet nearly half of those tags will remain unallocated at the end of the season.

So, in spite of the obvious and massive failure of the tag system, it still needs to be assessed? That’s just ridiculous.

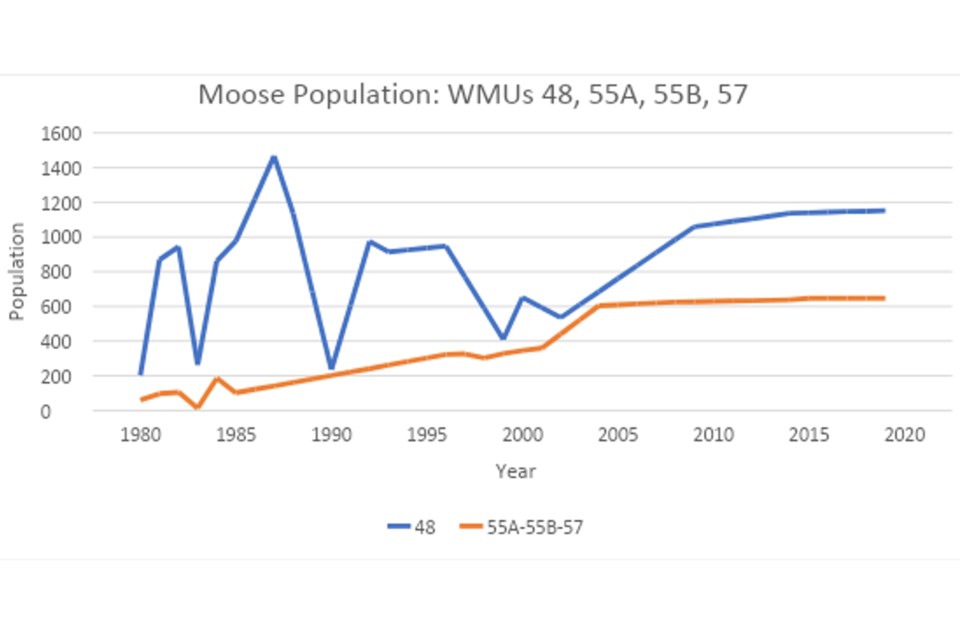

The actual “management strategy” of protecting calves and killing more cows (as presented in the 2019 review) has been in place in the “experimental area” around Algonquin Park since 2004. After nearly 20 years in practice, it should not require further study, either. In fact, on the basis of that “study”, it should never have been adopted at all.

I am assuming these units are the “evidence” of the program success mentioned in the minister’s letter. I make this assumption because I have seen nothing in the planning or harvest information that suggests success.

MNR staff have not pointed out specific WMU examples of success – although after four years, one would think every unit should demonstrate population growth. They have not provided any scientific papers to show it has worked elsewhere.

I provided the minister with the “data” from those units, and this graph, as positive proof that the “experiment” of killing cows and protecting calves is not going to restore the population. At best, it brought populations up to those in the 1980s, but has failed to reach historic levels.

While achieving 1980 levels might appear to be a sort of success, provincial populations were at their lowest level at that time. This experiment is an example of “reduced failure” more than an example of “success”.

It is interesting to note that all of the information recently presented by MNR dates back to the 1980s when the population was lowest. When the 1980s is used as a metrc, of course any increase would look like success. They don’t present (or perhaps ignore) the population information that I collected from the 1950s that shows just how far the population has declined. Perhaps this might explain why MNR managers think they are successful. They have no idea of the reality of the moose population before selective harvest.

The information from units 55A, 55B and 57 was pooled because several of the surveys aggregated WMUs and I was not provided estimates for individual units.

Note that only WMU 48 has reasonably good information, and there were only three surveys after 2002. It alone accounts for all of the population growth from the calf protection strategy, but there was a whole lot more going on there than just protecting calves. The other units did show growth, but that was before calf protection.

Note that the WMU 48 estimates were up and down erratically. This is not a measure of real population change, but of poor-quality surveys in this area. There were periods between surveys, often six years but 13 and 17 years in some cases. There is also a strong possibility that part of the “success” was through emigration of moose from the park.

I pointed out to the minister that no competent scientist would draw the conclusions that Ontario biologists have from this information.

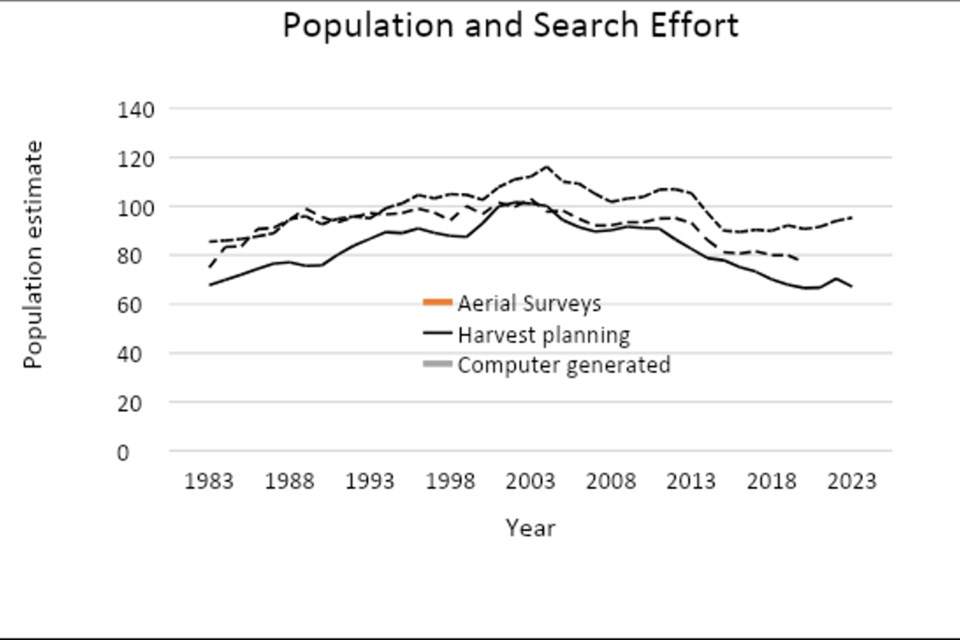

I have previously commented on my skepticism of hypothesis-based (or computer-based) management.

After waiting three months, I got some of the population information I requested through Freedom of Information and updated an old population table by simply interpolating between survey estimates, so there was an estimate for every unit every year.

Not fancy, but it uses real population estimates with a few simple assumptions. On this evidence, it appears the population has dropped much more than expected (34 per cent) and has not rebounded as the computer predicts. It is also interesting that the population used for harvest planning (the “hunted” population) is higher than the aerial surveys, which include all WMUs in the core range, including parks. This possibly explains why planned harvests cannot be achieved.

A recent webinar identified that disease and hunting are the main factors regulating the moose population, yet MNR managers and BGMAC continue to mismanage hunting. Comments made in that webinar suggest there is little interaction between scientists and harvest planners.

The advertisement for that webinar stated that moose (hunting?) contributed $200,000,000 annually to Ontario’s economy.

If it was based on recent hunter numbers, it would mean each hunter contributes $5,000 to the economy. Even considering multiplying factors as direct hunter expenditures flow through the economy, it seems like a large number. It probably relates to a time when there were more hunters, and certainly more moose.

In that case $130,000,000 has been lost annually as hunter numbers dropped to 40,000.

Assuming the estimate was from the early 2000s, then the value of moose would likely exceed $500 million if my assessment of the population potential is correct and both moose and hunter numbers rebound.

Either way, the mismanagement is a blow to the economy of Ontario, and a major blow for Northern Ontario.

Because there is no legal access to “why” questions, I asked that Mr. Smith, the minister, have his staff provide me, and especially him, with referenced publications supporting calf protection and a high cow harvest, including examples of WMUs where they claim success.

Because Ontario’s program is so radical and inconsistent with both good animal husbandry and the rest of the moose management world, he should be assured in knowing that it was founded in good science, as demonstrated in other jurisdictions, and not the junk science from the “experimental” area.

I asked him to have his moose managers explain how, and specifically what, information was used to establish population objectives. I asked this question because Ontario management population goals are well below historic levels. They are based on an undescribed computer simulation, the “standard habitat model”, rather than real adaptive management that tests strategies and measures success from real, live moose populations, not computer models.

Managers have only set population objectives and those could be achieved by doing nothing. Even continued population decline in some areas is acceptable. They allude to social and economic benefits, but haven’t set clear objectives for those.

Nobody can quantitatively criticize the lack of success in this area. Based on the $200-million value, the loss of hunting opportunities looks like a major failure. They need a computer model to estimate how many jobs, how many recreational days, direct expenditures and the added benefit to tourism that each new moose might generate through hunting or the stimulus of people seeing them while fishing, canoeing or driving.

They might use that information as an incentive for better management, since they don’t seem concerned about the population.

Finally, I pointed out to Mr. Smith that by letting the people who are creating the problem write “his” response, he is enabling them to cover their incompetence under his name. I would hope that as the official leader for resource management in Ontario, he is wise enough to understand this without it having to be brought to his attention.

An old adage states “when you get conflicting information, you should side with the source that has the least to gain.”

My interest is, and has always been, effective moose management, not hiding incompetence. I’ve made mistakes, but fortunately they weren’t serious, and I believed I learned from them. Perhaps this is what has set me against current management practice.

On that basis alone, Mr. Smith should accept my assessment over that of his staff. This is especially true because it is based on their own information. It is made in the absence of anything scientifically acceptable, or anything at all, from them to support their strategy. He should demand real evidence that the strategy is working, or he should demand change.

If he chooses not to accept my assessment of the situation, then at the very least Mr. Smith should initiate an independent review of the moose management program by competent resource scientists.

Since both MNR staff and I might be biased in a recommendation of who could carry out this review, I would suggest he contact a former MNR employee who might be able to recommend some folks. He was a habitat specialist from about 1975 to the early 1990s. As such, he was an important part of the moose management team and understands the history and current problems. He became, and retired as, dean of science at Lakehead University.

If Mr. Smith fails to change Ontario’s moose management or initiate a review, the consequences of the continued failure — possible complete season closures and the loss of $200,000,000 annually — should rest on his shoulders alone.

It has been three months and there is still neither acknowledgement nor response from the minister’s office. Apparently, he isn’t as interested in moose management as I was told.

Alan Bisset is a retired regional moose biologist and wildlife inventory program leader with the former Ministry of Natural Resources. He has written and published many papers on moose management, both Internally and in scientific journals. Bisset lives in Strathroy, west of London, Ontario. You can find his other submissions by typing “Alan Bisset” into the searchbar at Sudbury.com.